The Paradise 101 exhibition summarizes 29 years of photographing Japan by one artist: Wojtek Wieteska. Two minimalist spaces at the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Kraków are filled with 411 metres of photographic paper presenting 555 images. Joanna Kinowska speaks with the curator and artist about Japan, time travel and the photographer’s archive.

Joanna Kinowska: The numbers are enormous: 555 photographs, almost 30 years of capturing Japanese reality. Additionally, the very best venue for presenting an Asian-themed exhibition. Before we talk about your vision of Japan, I have to ask what intrigues you about this country the most?

Wojtek Wieteska: I am captivated by the unique mentality and organization of space. The atmosphere of the island. The advantage of fish over meat. The simplicity, especially in expressing beauty. The lack of attachment towards the idea of ‘authenticity’ and ‘copy’. The oldest Shinto shrine in Ise is by design rebuilt every 20 years. It is so refreshing! It means that the whole entourage of classical photography with its hierarchy of closed editions is very conventional. But mostly, I understand Japan through the forms and through art. I have spent there eight months in total. The last time was in spring 2019 with my partner Ania, the curator of Paradise 101. As soon as flights to Tokyo are unfrozen, we want to travel to Hokkaido. I sense there are some winter landscapes with my name on it…

Originally, Wieteska’s Japan was all black and white. Now it is colourful, and snowless, as you said. How have your optics changed over the years?

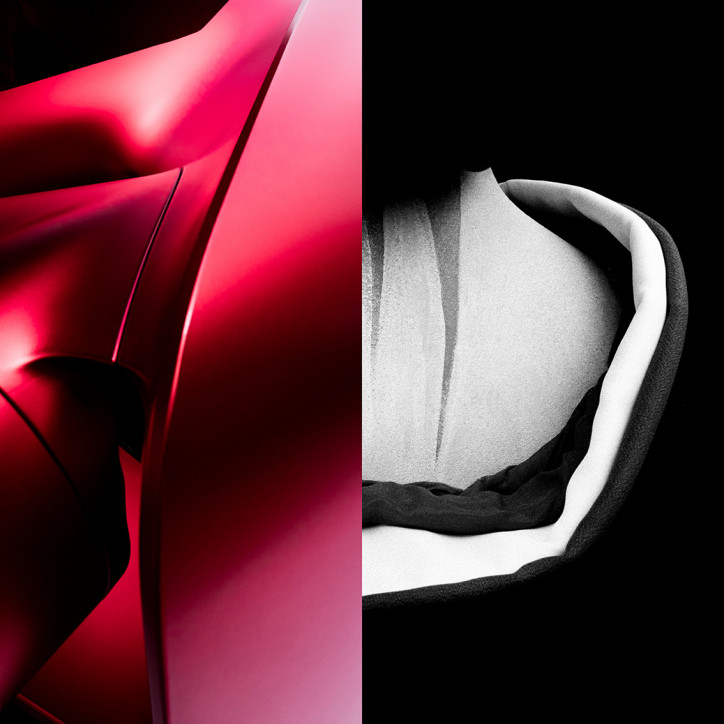

WW: It has not changed, only my mind evolved. And how exactly is best exemplified by the two identical spaces of Manggha Museum, which are placed one over another. They host entirely different photography installations and narrations. Just like the leitmotiv of Paradise 101, communication, suggests where we paired a black-and-white image from 1996 with a red photograph from 2019. Two worlds, of analogue and digital photography; one thought.

Let’s talk about this evolution then. The sum of experiences, films watched, books read, life changes, etc. They must be relevant to your perception and style of working.

WW: Sure, but I believe more in subtraction than addition. Balzac stated that that each photograph ‘peels