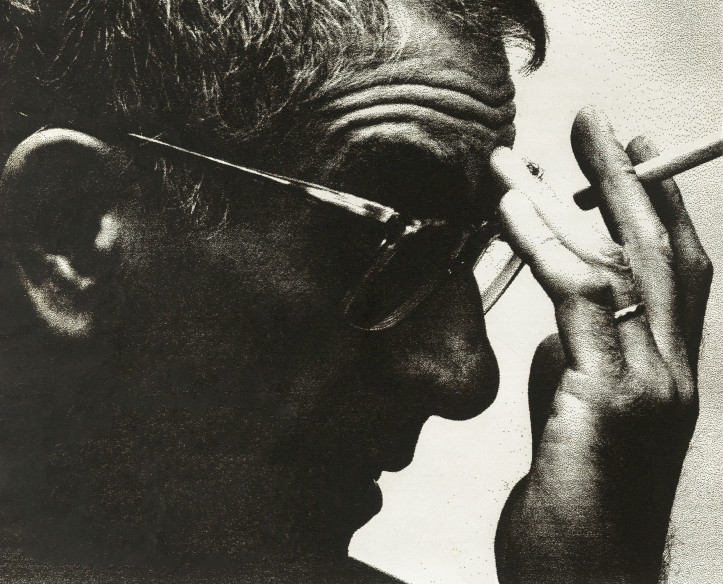

The Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski is known across the world as one of the leading arthouse auteurs of the late twentieth century. Starting out as a documentary film-maker, Kieślowski then went on to make a number of fictional feature and television films in his native Poland. In 1988, he created the television cycle Decalogue , the success of which enabled the international co-productions The Double Life of Veronique and the Three Colors trilogy. On the eightieth anniversary of his birth, we look back on an interview with Kieślowski, originally published in Przekrój in 1994.

Krzysztof Kieślowski’s films are loved the world over. He invariably tells a simple little story, with small-scale metaphysics in the background. People are moved when they leave the cinema. This is how Kieślowski, an excellent documentarian, became one of Europe’s finest film-makers.

On the Road

Kieślowski got more from life than he had expected. He says: “When I was a child, we moved all the time: furniture, towels, books and bedding in tow. I never had a fixed place I could call my own or a permanent group of friends; even the objects around me would change from one moment to the next. I’m not complaining: this is what my world was like and, looking back, I think I liked it. My father suffered from tuberculosis and went to sanatoria for treatment. And so we followed him . . . It wasn’t always easy for my mother to find a job and a place to live in the same town; if it proved difficult, we would find a place nearby. But sometimes, we had to move quite far.”

As a boy, Krzysztof was never a fan of cinema. He knew nothing about cinema. As was often the case with small towns immediately after the war, touring cinemas would visit once a month at best wherever Kieślowski happened to be staying. “When we lived at Strzemieszyce, at my paternal grandmother’s, my uncle, a renowned local doctor, persuaded the usherettes to admit me to a screening of Fanfan la Tulipe. I must have been about ten, and Fanfan was an X-rated movie. This is one of my very few cinema-related childhood memories. I can’t remember much of Fanfan, either.”

Kieślowski was drawn to theater. When he was a student at the State School for Theater Technique in Warsaw, the thought he may one day make films had never crossed his mind. By contrast, being a theater director seemed like an interesting prospect. But theater directing was (and still is) a postgraduate course. “I was sure the Film School in Łódź would provide me with solid foundations for working in theater. My two attempts to get in failed. So I decided I would be admitted to where I wasn’t welcome. My third attempt was driven by ambition, and I got in. What do I owe to the Łódź school? Technical skills, of course—but also friendships (very serious friendships) and encounters with teachers who opened my eyes to many things I knew nothing about.”

As early as in Decalogue, Kieślowski emerged as a superb artist: he felt more deeply than others, had a better grasp of things. Why, then, was he once fascinated by documentaries? Surely this genre puts constraints on the artist’s imagination? “Not necessarily,” Kieślowski replies. “It is true that a documentary doesn’t go beyond depicting reality—but this is done from the point of view of whoever makes the film. It was documentaries that unleashed my imagination.”

A Camera in the Courtroom

In the 1970s, Kieślowski was hailed as one of the world’s finest documentary makers. In 1982, he decided to make a film about political trials during martial law in Poland (1981–1983). After a protracted waiting period, he was granted permission to enter the courtroom with his camera—by which time the political trials had as good as come to an end. But, Kieślowski recalls, a more serious obstacle emerged: mistrust.

“At the time, a person with a camera brought television to mind, and television stood for lies. Neither the defendants nor their barristers trusted us. I had to win them over. Among the many barristers I met during this time, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, then a young counsel, was the first to grasp the role of the film camera in the courtroom. He sensed the camera was his ally; it could be useful to him as a barrister. In the courtroom, the camera aimed at the judge is a witness. In a nutshell: my film was to be composed of scenes of passing harsh sentences, and two multiplied faces: that of the judge and the defendant. I never made that movie. Whenever we witnessed a trial with our camera, the defendant was either acquitted or received a suspended sentence. And so I began to be asked—by Piesiewicz and later by other barristers—to place my camera not just inside regional and district courts, but also in court martials (we were granted the relevant permission). I hired a few more cameras: they were in use wherever a political trial went on. Altogether, tens of acquittals were granted, or suspended sentences passed, when we were in the room. It struck me that, if the presence of a camera has this sort of impact on a judge, a feature film could be made about it. I knew nothing about the law, or how courts operated, so I decided to find a writer who was familiar with these issues. This is how Krzysztof Piesiewicz and I began working together.” they were in use wherever a political trial went on. Altogether, tens of acquittals were granted, or suspended sentences passed, when we were in the room. It struck me that, if the presence of a camera has this sort of impact on a judge, a feature film could be made about it. I knew nothing about the law, or how courts operated, so I decided to find a writer who was familiar with these issues. This is how Krzysztof Piesiewicz and I began working together.” they were in use wherever a political trial went on. Altogether, tens of acquittals were granted, or suspended sentences passed, when we were in the room. It struck me that, if the presence of a camera has this sort of impact on a judge, a feature film could be made about it. I knew nothing about the law, or how courts operated, so I decided to find a writer who was familiar with these issues. This is how Krzysztof Piesiewicz and I began working together.”

Does screenwriting get easier when two people are involved? “Yes. And no,” says Kieślowski. “Writing by myself is easier, but if I do that, I’m left without a partner. It is more difficult to write as a pair, but if I do that, I’ve got a partner. In screenwriting, partnership is about partnership. This sounds simplistic, but that is how things are. We both try to complement what we know and what we feel – and our feelings are often disparate, coming as we do from two different worlds – and then make all this into a whole.”

Decalogue and The Double Life of Veronique marked the start of Kieślowski’s brilliant, worldwide success.

Working with the West

How did a Polish film-maker make it onto the French scene? “I didn’t have any specific country in mind; in fact, I hadn’t thought about working abroad at all,” says Kieślowski. “In the late 1980s, several French producers told me they would fund my film if I made it in France. Shortly before that, I was getting numerous other offers from abroad: Switzerland, Italy, Germany and the US. Books to be adapted, screenplays to be rewritten. I wasn’t actually interested in any of them and decided to wait. And when completely unqualified offers did come up, they came from France: ‘Why don’t you do something here, and we’ll find the money.’” Although Kieślowski has plenty of experience working with superstars, he says: “No superstars ! No huge budgets!”

When it comes to finances, Kieślowski the director does not crave absolute freedom. He found the golden mean by himself: each of his films costs between four and six million dollars, which is within an average European budget. “With this sort of money, one can make a decent film, with enough shooting time (eight to nine weeks is what I usually need), fine actors and good-quality technical resources. I was granted all that in France,” says Kieślowski.

So far, he has worked with two producers from Western Europe, but never found himself under pressure from them. “Directors often complain that their producers pressure them into compromising, making changes to casting or dialogue, but I happen to come across people with whom I am able to reach an agreement. From the outset, my producers and I have managed to agree on our approach, budget and deadlines. I took both my producers and our agreement seriously. They have never put pressure on me when it came to casting, screenplay, finances – or the ending of the film. They have made numerous suggestions, many of which I took into consideration. Some even got implemented, although matters never came to a head. The advice I got was mostly good, often better than my own ideas . . . I know I sound old-fashioned, but this is indeed what my relations with the producer look like. I’m lucky, I know that.”

The Meaning of Things

Using the oesophagus to enter the viewer’s belly with a camera—this is what Kieślowski aims to do. He tells the simplest stories, with small-scale metaphysics in the background. To many viewers, these stories come as a shock, a revelation. Some emerge from this encounter with their world-view utterly transformed. Does this mean they are normally incapable of philosophical reflection? Or is it that they find their own feelings embarrassing and prefer to hide them from themselves?

“All these things at once,” replies Kieślowski. “As you said, I’m talking about simple matters using the simplest of languages—but I always ask an additional question.” He adds: “Everyone—it doesn’t matter if they are professional philosophers or shoemakers—carries within themselves the question about the meaning of things, and they search for answers. They’ll never find these answers. I ask these questions publicly, through my films, and people are quick to grasp these are the same thoughts and questions they carry inside. Let me give you an example: one dreary winter day in Warsaw, after I’d finished Red, I bought a collection of poems by Wisława Szymborska. The book was meant for my translator in France who loves Szymborska’s work. And as I leafed through it, I found a poem called “Love at First Sight.” I read it and it turned out it addressed exactly the same issues I’d just made

a film about. In other words, in mid-1993, two people—Wisława in Kraków and myself in Paris—thought about the exact same things in exactly the same way. I needed several million dollars to express them, while Wisława needed a little more than ten lines. This means people can have thoughts in common, even though they don’t know each other. My feeling is I can expect the same of people coming to the cinema – even if they refuse to admit to themselves they are so weak, poor, lonely and helpless as to be in fact powerless. A film has to touch some aspect of the viewer’s emotions. It doesn’t matter if people will laugh or cry at the cinema. Quite simply: I want viewers caught in an emotional trap.”

Directorial Minimalism

Kieślowski needs to plan how to do this two to three years in advance. He and Krzysztof Piesiewicz often wonder about the things people have had enough of, the language they no longer want to hear. They think about the language people are happy to use today, and one they will be happy to use in two years’ time. Kieślowski and Piesiewicz also wonder what the air will smell like in two years’ time.

Juliette Binoche once said she would abandon any ongoing work on a part to act in a film by Kieślowski. What does his work with actors look like? “My system isn’t about working with actors at all; it’s about trusting them,” he says “Casting someone means I trust that person. I believe an actor will find everything they need to build their part in the screenplay and in themselves. I was never disappointed. Every actor is ready to work in this way: you only need to give them a chance. When I cast Jean-Louis Trintignant as a judge in Red, he told me straight away: ‘I know, I know everything.

I know who this person is: I’ve played a lot of parts and I’ve lived plenty. You don’t need to explain anything.’ A good actor doesn’t need a single psychoanalytic conversation with the director. They know. At times, I’ll give the cast three sentences; sometimes, it’s just one. And then I make small adjustments: ‘Keep your voice down in this scene’, ‘Speak up’, ‘Now stand up’. But I also wait for actors to give me hints about when they should stand up; and I hope their ideas will be much better than mine. When we were shooting Red, Trintignant had a bad leg and walked with a stick: he was unable to move without it on set. And so the entire staging concept drafted in the screenplay had to be changed. You ask me if such situations add to a film, or take something away from it. I don’t know. I always want actors to find their own approach to the world; to find their characters by themselves. Even if it’s about nothing more than a walking stick.”

Music as Drama

In France, the CD of Double Vie de Véronique sold a hundred thousand copies; as with Nino Rota, people like to listen to Zbigniew Preisner’s film scores in the comfort of their home. What draws him to Preisner? “The way we work,” Kieślowski replies. “If we decide to make a film, we meet at the very beginning, before a screenplay is written, and the whole film amounts to a general thought.

“This thought could be written down in three or four lines. And, already at that stage, Zbyszek [the diminutive form of Zbigniew Preisner’s first name—ed. note] asserts himself. That was the case with Red, too. Zbyszek first read a few sentences, then three versions of treatment, then four versions of the screenplay—but as early as the first version of the screenplay, he told me he felt he needed to play a bolero in this film. You would think that’s nothing special, but to me it was a revelation. Zbyszek explained bolero was a repetitive piece, developing with each repetition, becoming ever richer, whether musically or instrumentally. I thought about this as I shot the film, and I think Red as a whole is the structure of a bolero put into practice. There isn’t that much of Preisner’s music in Red, but, from the very beginning, I relied on his way of thinking about music as the dramatic tissue of the film. And it’s this kind of communication with him that interests me most. It’s not so much an inspiration as a state of mind. You can see for yourself how many people make an impact on the form a film will eventually take.”

The Next Generation

Is film in crisis towards the end of the twentieth century? And what about literature? Who can think of as few as three great authors writing today? In Kieślowski’s view, a few genuinely good films would be enough to make people return to the cinema immediately.

“It takes talented, energetic people to make a good film,” says Kieślowski. “In the past, this was never an issue. When Tarkovsky was alive, when Fellini, Bergman and Kurosawa made their films… Whereas today? We, directors, are biologically the next generation, and so we took over from our predecessors, but I’m afraid we are no match for them.”

Ordinary Life

Family and friends (and acquaintances) slip away from Kieślowski’s life. Making a feature film (Kieślowski completed his Three Colours cycle within a short period) cuts him off from his personal life. Is that the price he is paying for practising his profession?

“I no longer practice it,” Kieślowski replies calmly, “so I’ve already paid my price and now I’m trying to return to ordinary life which, in my view, is far more important than film-making.”

Kieślowski’s fans are convinced that one day he will once again play the game of ‘getting viewers caught in a trap’; but, for the time being, he has undoubtedly set a trap for himself.

This feature was originally published in “Przekrój” (no. 2559 / 1994). You can read the piece in Polish in our digital archive .