A celebrity singer and a future celebrity architect together created an unusual hotel in the mountains. They named it for the glory of the homeland.

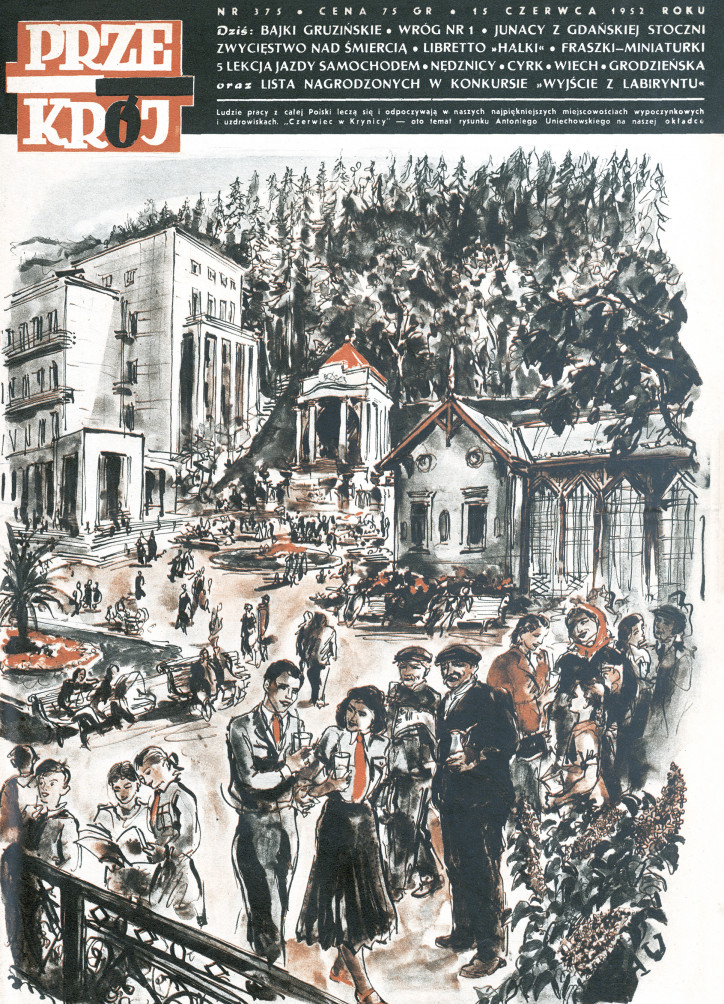

Krynica-Hawana bus stop. The beginning of autumn; the end of a long journey. A cold Sub-Carpathian night descends, but the fire burns on the exotic islands of dance halls: summer hits from the last 40 years are being blasted, dancing couples forget about their age. In sanatorium spa resorts, time gets curved in a weird way. It is ruled by a daily rhythm of meals, walks, treatments and dance parties. What day of the week, what year is it? Does it even matter?

Time also gets curved in the state-run spa resort called Patria. It fulfils fantasies about the lives of the elites of the Second Polish Republic in the times of the communist Polish People’s Republic, and at the same time makes one think of Wes Anderson’s films. It was created at the beginning of the 1930s, commissioned by the world-famous singer, Jan Kiepura. For the artist, blessed not only with vocal talent but also with business flair, it was a way of investing his money made performing abroad. He also reckoned he might be able to save his parents’ marriage this way. If they were to live together in Krynica and run the family business, surely they would be able to find common ground?

The name ‘Patria’ suggested an investment for the glory of the homeland. In interviews, Kiepura stressed that even though he had performed on two continents, he never forgot about his country, and that by creating a world class establishment he might bring foreign guests into the Polish mountains, too. And that he only used Polish building materials.

The building project was commissioned by Kiepura in 1930 from Bohdan Pniewski, who at the time was only 33 years old and had an ambitious plan: he wanted to become the biggest Polish architect. By then he had won two prestigious competitions – for an embassy in Sofia and for the Warsaw Temple of Divine Providence. However, the thing with competition projects, is that unfortunately they can get stuck on paper. The promising architect Pniewski needed a client who could finally let him build something grand, while Kiepura needed a talented and respected designer. Preferably quite young and inexpensive. Supposedly the singer tried to buy the designs for half the price or even a tenth of the price, to which the architect allegedly said: “For this kind of money I can sing for you.” It seems that somebody met his match.

Pniewski succeeded in defining his own authorial style in Krynica. Patria is a modern structure in reinforced concrete with spacious terraces, large glazed expanses and a flat roof-terrace promoted by Le Corbusier. Yet Pniewski did not approach the commandments of modernity with Protestant strictness. After all, one can always go to confession! While designing the free-standing structure, which can be seen from three sides, a faithful modernist would have composed each of them with equal attention. But in Patria, the front facade knocks you off your feet, the side facades are also well-thought-through, but the back was quite clearly given up on, and is as boring as the back of a tenement house.

The terraces at the front were stylized in such a way by Pniewski to make you think of a Renaissance cloister. This echoed his fascination with italianità, which started during his year-long scholarship spent in Italy. However, the interiors were art deco in style: veneers, mirrors, marbles, cascades of modernist glass-and-nichrome chandeliers, alabaster railings letting light through and looking like some weightless mousse or meringue. Yum!

A bar with a dancing floor was located in the basement; a reception, a huge living room separated from a dining room with a glazed folding partition were on the ground floor; on the mezzanine was a bridge room; and on the following floors were hotel rooms. The ones in the front face southwards, so the sun gets in through most of the day. The other ones differ in standard: from big apartments for celebrities and royalty to rooms without bathrooms. Kiepura wanted to create a place to suit every pocket. I suspect that he was aware of the thin layer of Polish customers able to pay for real luxury, and hoped that he would fill the building with middle-of-the-road players, who, either out of snobbery or nosiness, would choose the hotel where they could see a real prince or some other Hanka Ordonówna.

When on Christmas Eve 1933 Patria was formally opened, the press rhapsodized over it. Finally a European-level hotel! But in the professional magazine Architektura i Budownictwo [Architecture and Construction] the architect Romuald Miller was very critical. A mountain hotel should be a modest, functional relaxing machine. There is no space for extravagance here, for expensive materials or references to the Renaissance. Music critics reprimanded Kiepura in a similar tone. With his voice and fame he could shape mass taste and educate the public, but instead he openly admitted he didn’t understand Szymanowski, had a penchant for dishing out operetta hit songs, and shone in film musicals as a regular beau.

Miller accused the author of Patria’s design of betraying the ideals of modernism. But by that stage, Pniewski could afford to dismiss the critics. When the hotel was about to open its doors, he was busy designing a new Ministry of Foreign Affairs building in Warsaw for Józef Beck and had won the second competition for the Temple of Divine Providence – in front of his studio had formed a queue of wealthy and notable men planning villas and tenements. Customers were not after avant-garde, but after compromise. Just like in the case of Patria, which, while taking advantage of the achievements of modernity, still felt like a continuation of tradition. This authorial formula, indisputable talent and chutzpah carried Pniewski through the following decades. He became the darling of the Polish People’s Republic’s authorities, thanks to which he built quite a chunk of the post-war capital: the buildings of the Ministry of Communication, the Parliament, the National Bank of Poland, the Polish Radio, and the Grand Theatre.

Still, one thing can be said about Patria – it is bearing up well. It is almost 90 years old now and it has never undergone an overhaul. Most of the furniture disappeared during the war, but the stone cladding survived, as did the stuccos, the tiles and even the windows with the ingenious levers opening the vents without the need to climb a chair. The spacious lift with a bench also survived. It used to be operated by a lift attendant, but now visitors need to bother the nice lady at the reception. So, out of courtesy, we take the stairs. Quite a lot of architectural fixtures survived too: the door handles, the buttons and the switches.

The building clearly did and is still blessed with good managers, who repair and replace things on a regular basis without interfering with the historic matter. Nice, busy staff bustle about the clinically clean rooms. You feel as if you’re visiting some elderly couple whose pensions haven’t allowed them to renovate, so they compensate the lack of funds with care; they scrub, polish and wash. And they would give their guests the world.

Care and thriftiness are, however, not enough to keep Patria alive. The front facade is crumbling away. On the other hand, it’s scary to think what might happen if some zealot started adapting the hotel to the standing building regulations or contemporary ideas of comfort. Another Kiepura would probably be needed, an artist and entrepreneur, who would understand that first and foremost this is an architectural icon and only then tourist accommodation. In our hurray-patriotic times, this kind of patronage can be expected from the state. After all what kind of patria would it be if it couldn’t afford to save Patria?

Translated from the Polish by Anna Błasiak