The Sumerian sky goddess Inanna had a necklace and staff made of lapis lazuli. Pigment obtained from the rich blue mineral was used to paint the Madonna’s robes. In fact, the rock, mined in the mountains of Central Asia, is vital to many cultures.

The cold, inhospitable wilderness of the Afghan province Badakhshan is a network of rocky peaks, furrowed with treacherous gorges. The mountain range of the Hindu Kush rises there, 24,600 feet above sea level. Its name fully reflects the hostile character of this place—in Pashto, Hindu Kush means “killer of Hindus.” Despite these adverse conditions, the mines here have been exploited continuously for more than six thousand years. They are used to extract lapis lazuli—a stone which has become an attribute of divinity in many cultures, and was one of the first luxury goods.

The Rarest of Pigments

Lapis lazuli (literally, “blue stone” in Latin) is a metamorphic rock, or one that was transformed deep in the earth’s crust. Today it is considered a semi-precious stone. It is of medium hardness, which makes it relatively easy to process. However, what determined its enormous importance is its beautiful dark-blue color, which it owes to one of its ingredients: lazurite. Ever since ancient times, stones and gems have been associated with beliefs, magical powers, and social status. They shouldn’t be treated as mere minerals—they are also elements of culture, mythology, and art. Gemstones reflect human motivations, aspirations, and anxieties.

For many societies, blue was a color with a symbolic dimension. This probably happened because people desire everything that is unattainable or unusual—and blue pigments are some of the rarest on Earth. In the few plants and animals that boast this color, it is most frequently part of their structural coloration. This means that their bodies contain no blue pigment, but in the process of evolution they have developed fine structures that refract light to generate various shades of blue. Wanting to obtain this color for themselves, humans had to reach for rocks and minerals. In antiquity, their choice wasn’t great. Apart from the very rare and hard sapphire and light-blue turquoise there was only lapis lazuli.

Throughout the ages, merchant caravans from Bactria (as Badakhshan was once called) loaded with the precious stone made their way to the cities of India, China, Rome, Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, a region located in the Tigris-Euphrates basin.

The documented history of lapis lazuli trade dates back to the Neolithic period. The earliest traces, some nine thousand years ago, come from the Indus River valley, where in the mid-70s, French archeologists began to explore the remains of the ancient burial grounds of a settlement called Mehrgarh and encountered many ornaments made from the stone.

About seven thousand years ago, the inhabitants of Mesopotamia—as possibly the first in history—had enough wealth and leisure time to start seeking luxury goods. They were overwhelmed by a desire for the blue stone. The languages of the region attest to its incredibly high value. For example, zagindurû, the Akkadian word for lapis lazuli (but also for blue pigment or blue glass) contains the root za-gin, which describes something shiny and precious. Interestingly, ancient languages didn’t usually have a separate word for the color blue itself. This is related to the above-mentioned fact that it rarely occurs in nature.

The exclusive character of blue meant that both in Mesopotamia and other areas it was reserved for those of high social status and the ruling classes. The usage of a whole palette of blue as the key ornamentation feature at the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud is a good example. The wall paintings there, as well as various architectural details such as glazed bricks, colored sculptures and large-scale bas reliefs were all blue.

In ancient Mesopotamia, large quantities of small, personal objects were made from lapis lazuli. These could be figurines of animals or people; jewelry or cylinder seals, which were used for impressing official signatures and religious inscriptions on damp clay.

Royal Tombs

Some of the most sophisticated lapis lazuli artifacts are undoubtedly those found in southern Iraq by Charles Leonard Woolley. In 1922, this British scholar of the ancient “Near East”—now considered a forerunner of modern archeology—took the lead at the excavation of Tell el-Muqayyar, which used to be the famed Sumerian city-state of Ur. After many setbacks, Woolley made a ground-breaking discovery. He excavated the ancient city’s necropolis from under a thick layer of desert sand and bricks. Present-day estimations indicate that the dead were buried there for almost 3,300 years.

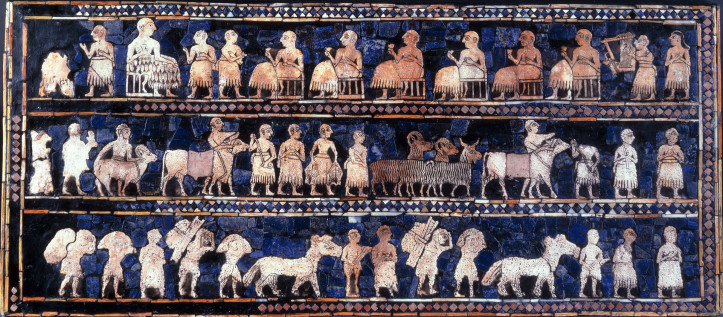

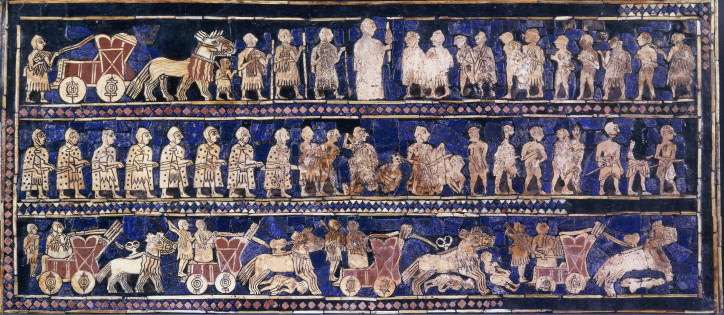

Woolley discovered more than two thousand burials there. The unique construction and furnishing of sixteen tombs, which he called “royal” on the basis of their inscriptions, stood out. In addition to innumerable items of jewelry, weapons, and golden vessels, the archeologists found a lyre—once belonging to Sumerian queen Pu-abi. It was decorated with a golden bull head and a stylized beard made of lapis lazuli. There were two gilded lambs resting against some golden thickets, with fleeces also made of the blue stone and shells. Finally, one of the most emblematic examples of Sumerian art was the famous ornate box, called the Standard of Ur, and also made of lapis lazuli and mother of pearl.

A Journey to the Underworld

The aforementioned stone is also the most frequently mentioned gem in Sumerian written sources. An approximately five-thousand-year-old history of the goddess Inanna invokes it as a crucial symbol of divine power. The myth tells the story of how the great goddess, the Queen of Heaven, descended into the underworld, struggled with her sister Ereshkigal—the Queen of the Dead—and finally restored the balance between life and death. While preparing for her journey, the fearless Inanna (later called Ishtar) donned the emblems of her divine powers, which doubled as the container of her magical talents—apart from her most splendid robes and the crown of heavens, she also had a lapis lazuli necklace and staff. The choice of this stone in the legend shouldn’t be a surprise, given that in ancient Sumer it was commonly associated with divine power. Sumerians believed that the stone houses the deity’s soul, which could be connected to through jewelry worn on the body.

Lapis lazuli also played an extremely important role in ancient Egypt, which was reflected in the language, just like in Mesopotamia. To name the color blue, Egyptians often used the phrase “lapis-lazuli-like,” and the hue, which to them symbolized the supernatural, was associated with the home of the highest deity Ra, heaven—its Egyptian name, shbd, was also used for lapis lazuli.

From the very beginnings of Egyptian statehood, lapis lazuli was used to create jewelry and amulets, and to decorate ornaments. The Egyptian Book of the Dead—a collection of magical texts aimed at helping the deceased in their journey through the Duat (the underworld) and into paradise—contained detailed descriptions of the use of the stone in burial rites. In the religious context, lapis lazuli was equated with resurrection, which is why many Egyptian handicraft items found in tombs contain the rock. In daily life, powdered lazurite was used by rich Egyptians as eyeshadow. Much later, this powder found application as a painter’s pigment, revolutionizing the European art world.

The Venetian Monopoly

Ultramarine was first used in the early Middle Ages. From around the thirteenth century onward, Europeans started experimenting with its formula in order to intensify its blue color. One of the recipes developed at the time was included by Cennino Cennini in his treatise entitled Il Libro Dell’arte: O, Trattato Della Pittura (A Treatise on Painting), which is still a rich source of information about the techniques used in the early Italian Renaissance. The goal of the lengthy and complicated extraction described by the painter was to separate pure lazurite from the other minerals constituting lapis lazuli.

According to Cennini, to obtain the pigment one needs to start with selecting the material for its lazurite content. The darkest fragments of rock were selected, and then burned, rapidly cooled, and finely ground. The resulting powder was mixed with liquid pine rosin, mastic, and beeswax. These procedures yielded a doughy paste called pastello, which was then kept at room temperature for a week and kneaded once a day. Later the paste was combined with heated potash, which extracted the blue pigment particles. Repeating the process several times yielded various gradations of color—from dark blue to a pale one, called ultramarine ash.

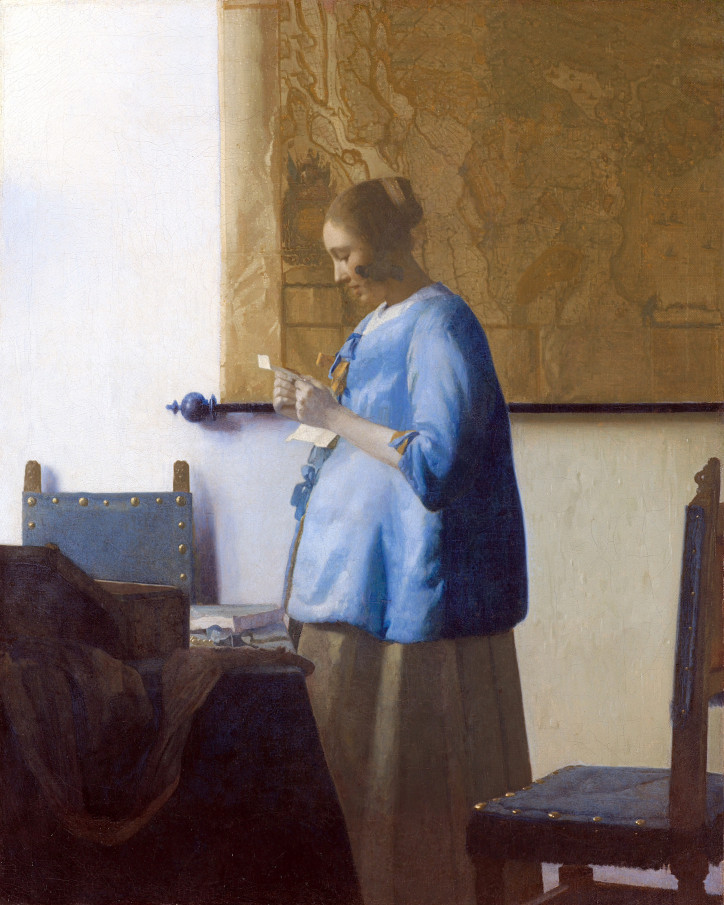

From the fifteenth century onwards, imports of lapis lazuli were almost entirely controlled by Venice. It was through its ports that shipments of the Asian stone arrived in Europe. This mode of transport also influenced the name of the pigment—ultramarinus means “from beyond the sea.” At that time, ultramarine was already the world’s most expensive pigment. Its prohibitive price quite often made it impossible for many famous artists to work. Michelangelo and Raphael had to count on the generosity of their patrons, and Johannes Vermeer’s predilection for ultramarine got him and his family into enormous debt. Today, the blue pigment is one of the Dutch Baroque painter’s most distinctive features—it appears in almost all of his works, and it was with its help that Vermeer achieved the characteristic brightness of strong daylight.

The discovery of Prussian blue at the beginning of the eighteenth century did not satisfy artists. It still wasn’t ultramarine: deep and durable. The synthetic version of this shade only became available a century later. In 1814, engraver and painter Jean-Joseph-François Tassaert accidentally noticed a residue with a color very similar to ultramarine in a lime kiln. This prompted the French Society for the Development of National Industry to invite proposals on how to synthesize the pigment. Two chemists, Jean-Baptiste Guimet and Christian Gmelin, were up to the task, and in 1828 this previously so expensive color became widely available. This doesn’t mean, however, that there are no more takers for real lapis lazuli. The mines of Badakhshan continue to operate, and the blue stone, the carrier of the loftiest symbolism of many glorious cultures, is still—aside from opium—the province’s main export.