We present artistic books on the pages of our print magazine, and the fact that we do is thanks to, among others, one Italian artist. He is loved both by children and by such intellectual masters as Umberto Eco.

“Never seen so much snow,” is how the Italian artist Bruno Munari starts the story of the Little White Riding Hood. On subsequent pages, we follow the story of the little girl dressed all in white, who is wading through snow drifts to get to her grandma, whom she hasn’t seen for a long time. Because of the blizzard, you can’t see a thing. The pages are white and the story unfolds, naturally, in our imagination. In his other book, The Circus in the Mist, the city of Milan is enveloped in a milky fog. On the pages, made of semi-opaque tracing paper, there are silhouettes of vehicles, street lamps and pedestrians hurrying in different directions. Ploughing page by page through the misty city, we finally arrive at the circus tent. We enter, and that’s when the book explodes with colours.

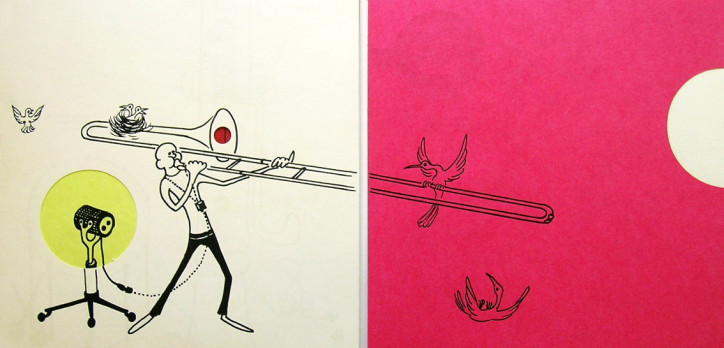

Reading each of Bruno Munari’s (1907–1998) more than 70 publications is an adventure, even if, in contrast