A century and a half ago, Jules Verne achieved great success with his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. The story features the mysterious Captain Nemo, an avenger in command of his own submarine. In letters to his publisher, the French writer described Captain Nemo as “a Polish aristocrat whose friends are dying in Siberia and whose nation is disappearing from Europe under the tyranny of Russia”. In the end, he had to modify his concept for commercial reasons, as a book containing this plotline would have been boycotted by Russian readers. But what would Verne’s novel have looked like had he stuck to his original idea?

Part I: The secret of the armour-plated narwhal

November 1867. French marine biologist Professor Pierre Aronnax and Canadian harpooner Ned Land are tracking a monster in the Pacific Ocean – the giant narwhal, which has been attacking local ships, makes the white sperm whale from Moby Dick look like small fry. They are suitably prepared with harpoon cannons, as well as a gun that fires 10-pound missiles over distances of several miles.

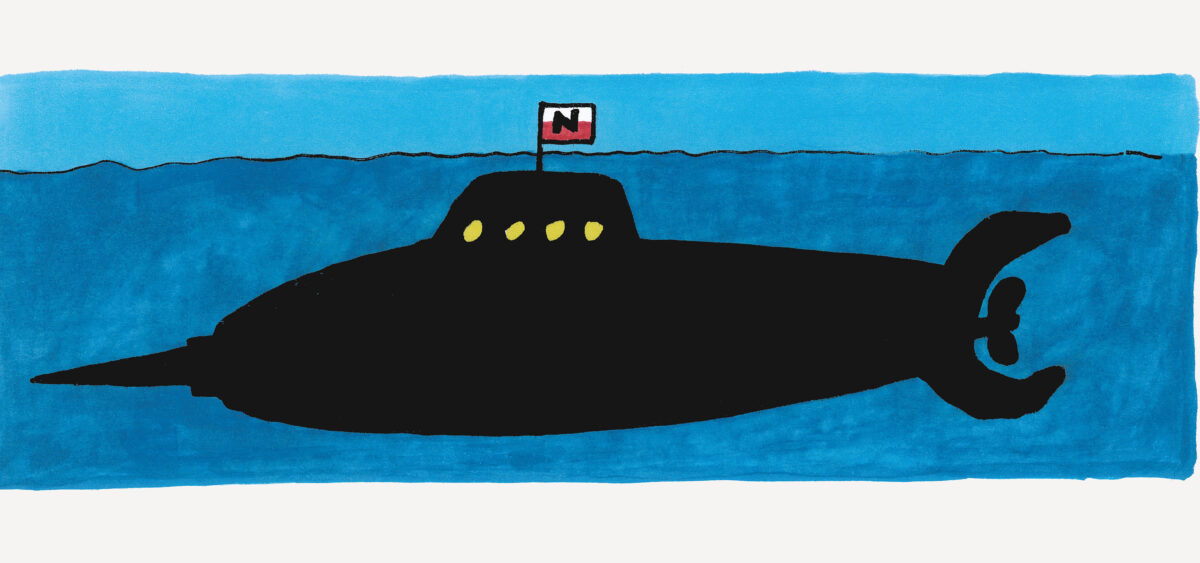

However, this gets them nowhere against the monster, which turns out to be not a living creature, but an armoured submarine! Aronnax and Land’s ship sinks to the bottom of the sea, and they, like Jonah, end up in the belly of the sea monster. There they are greeted by a well-groomed, bearded, middle-aged man who looks more like an aristocrat than a sea dog. He invites them on a coerced but comfortable journey, having introduced himself as Captain Nemo. Nemo: ‘nobody’.

Who is he? Why did he sink their ship, and others before it? The captain doesn’t want to talk about it. A visit to his salon, however, raises suspicions. His collection of etchings presents a series of heroes who fought against tyranny: the Greek Botsaris, the Polish Kościuszko, the Irish O’Connell, the Italian Manin, not to mention the Americans Washington, Lincoln and Brown. The presence of these Americans in particular, two of whom fought for the liberation of slaves, leads Aronnax to believe that he is dealing with a Yankee.

“Maybe he fought in the recent Civil War?” he says to his companion-in-misery Land, whose reticence makes him an excellent listener.

“Then why is he still fighting? The war’s over,” responds Land, dampening the French professor’s enthusiasm.

So maybe the key to the mystery of Captain Nemo is the name of his ship, ‘Nautilus’? The same as the Latin name for the sea cephalopods with the fabulous spiral shells. And the same as the name of the submarine designed in 1800 by the American engineer Robert Fulton for Napoleon Bonaparte.

“Aha, so he is an American!” exclaims Aronnax. And, playing dumb, he asks Captain Nemo about Fulton. Who knows, maybe he’s an ancestor?

“Fulton?” Nemo frowns. “That plagiarist?!”

“What plagiarist?” asks the professor.

“Fulton used the earlier fish-ship plans of Dr Fryderyk Hoffmann,” Nemo tugs angrily at his beard.

“I’ve never heard of him.” Aronnax sees that Nemo has taken the bait.

As he’d hoped, the captain continues his tirade. “I’m not surprised by your arrogance. Fulton stole away all the fame from Hoffmann. He was a decent patriot, a soldier and surgeon from Warsaw. He invented a ship which he planned to use to kidnap the famous Tadeusz Kościuszko – hero of Poles, Americans and revolutionaries all around the world – from the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg”

For a brief moment, silence falls. Aronnax wants to ask the final, most important question, but the captain doesn’t wait, he turns on his heels and leaves the room.

“So is he American or Polish? But what would a Pole be doing in the Pacific?” asks Land, confused. “Or maybe he’s French? He speaks as fluently as if it were his mother tongue. So who is he?”

“A revolutionary!” replies Aronnax.

The opportunity to get something more out of the captain comes at dinnertime. The men sit down to a meal of sea turtle tenderloin, dolphin liver, whale milk cream and anemone preserves. Nemo likes to eat, he’s clearly no vegetarian, and he has exquisite taste. Expensive taste. Just like all the furniture, paintings and other artworks on board – not to mention the Nautilus itself, this miracle of technology. Nemo explains in detail how the ship is powered; Aronnax and Land nod along, although they understand little of what he’s saying. They swallow even the most exaggerated figures like hungry pelicans, including those relating to Nemo’s fortunes.

“I have vast amounts of cash,” boasts the captain. “I could easily pay off France’s billions of debts.”

Aronnax is about to ask why the captain attacks and sinks ships, piercing them with the long spur on the Nautilus’ bow like a narwhal’s tusk. There’s a remarkable cruelty to this method… But again, the professor misses his chance as Nemo decides to take his guests for a walk – along the seabed.

Wearing heavy diving suits that make them feel sick (especially after eating), they roam the undersea forest at the bottom of the Pacific. As a marine biologist, Aronnax is fascinated by the abundance of life in the ocean – so much so that he doesn’t notice when a metre-wide, cross-eyed sea spider lunges towards him. Fortunately, Nemo is alert to the threat and fells the monster with the butt of his harpoon cannon.

“He was a real king among spiders,” jokes the captain, his laughter resounding in the iron helmet like a bell.

Part II: The oppressed

If Aronnax still had any doubts at that stage about Captain Nemo’s nationality, they were dispersed the very next day. On the shores of New Caledonia, the alarm is raised aboard the Nautilus: ahead of them is a ship flying the French flag.

“Could our journey be coming to an end?” wonders Land. “Perhaps Nemo is a pirate in service to France?”

No. The ship on the horizon is a target. Locked up in their cabin, Land and Aronnax have no idea what’s happening. All they can hear is the sound of constant impacts. In the evening, over dinner, Nemo briefly explains to them what happened.

“Don’t worry, Aronnax. I’m not hunting Frenchmen, where did you get that idea? After all, I myself… anyway, never mind.” Nemo tugs at his beard again. “I just had to stop that ship to free an innocent man who was being transported like a slave.”

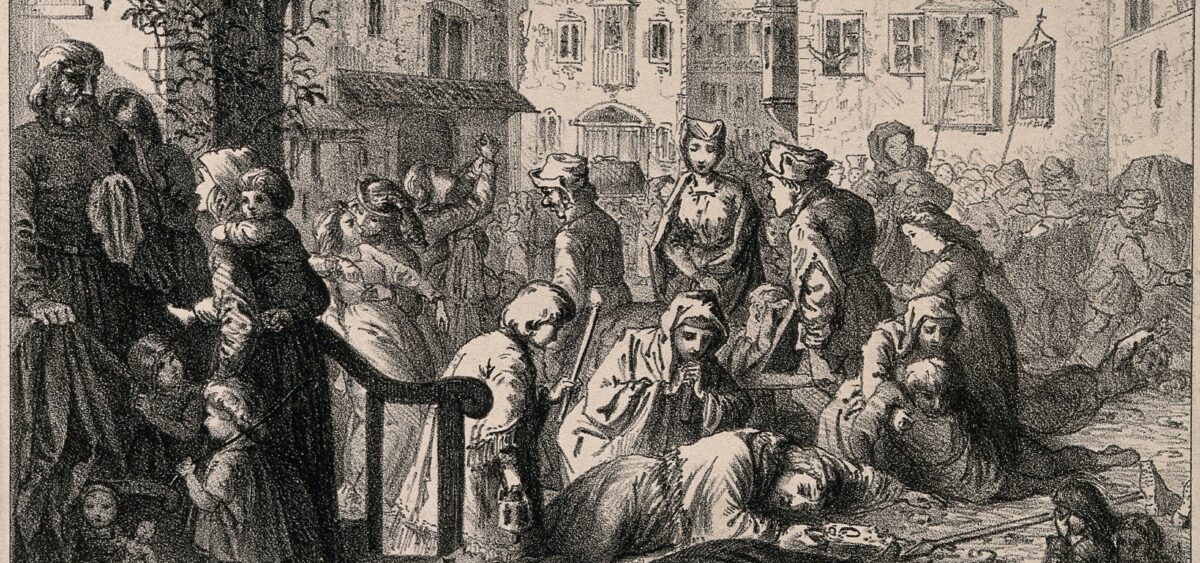

The man’s name is Antoni B. Of course Aronnax has heard of him! He’s the hero of a huge scandal, a Pole who took part in the January Uprising and emigrated to France following its defeat. There, he was shocked to see the French Emperor and the Russian Tsar parading around Paris together as thick as thieves. One day, their carriage is lying in wait in the Bois de Boulogne. As they arrive, Antoni B. takes out his pistol and shoots. He misses, the bullet hits a horse. So he shoots again. This time, the bullet tears the barrel of the gun apart! The Pole is captured and brought before the court. His sentence: deportation to the French colony in New Caledonia, at the end of the world, in the Pacific.

“And what will you do with this… um… innocent man?” asks Aronnax with a sneer. “Will he be joining your pirate crew?”

“Far from it. He’s not a man of the sea. He will be my representative in Australia,” replies the captain.

Land looks at Aronnax and the same thought occurs to them both: “So he is Polish! A revolutionary, like all the rest of them.” The commander of the Nautilus interrupts their exchange of knowing glances.

“One more thing, gentlemen. I’d like to invite you to a ceremony taking place an hour from now,” says Nemo slowly, as if choosing his words carefully.

“A ceremony?”

“Yes. One of my men was killed in the attack. We’re going to lay him to rest at the bottom of the sea.”

The ceremony is modest but rather oppressive, not least because of the pressure on the ocean floor. An undersea glade, a tomb made of rocks and a coral cross. Silent sailors leaning on the hoes they used to dig the grave. Captain Nemo meditating with his arms crossed. “Is Antoni B. hiding in one of these diving suits?” wonders Aronnax. “The man for whose freedom this sailor died and was buried at the bottom of the ocean? How many more lives has this madness cost? Couldn’t all Nemo’s inventions, money and enthusiasm be used for the good of mankind, not to sow terror?”

Antoni B. disembarks the Nautilus off the coast of Australia. Before leaving, he talks at length with the captain – as far as Aronnax can tell, they’re speaking Polish. The name Strzelecki comes up several times, a name that Aronnax knows well. He’s a traveller, an explorer of the Antipodes. Apparently, he has discovered some incredible gold deposits. So, when the young Pole leaves the ship – this time with books and maps under his arm, not a gun – Aronnax becomes convinced that he’s going to trace the veins of gold described by Strzelecki.

“I wouldn’t go ashore in this heat for any amount of treasure,” murmurs Land, burrowing away in the depths of his cabin. He’s been listless of late. The lack of physical exercise and the enforced isolation bother him a great deal. He only comes to life when admiring the skills of a local fisherman diving in search of pearls off the coast of India, where the Nautilus surfaces. But the fisherman’s life is endangered by a sudden shark attack. Land shouts for a harpoon and is about to jump in and help him, but Captain Nemo is faster. He does away with the sharp-toothed sea predator, just like the huge spider before it, and the giant octopus that’s yet to come.

But let’s get back to the fisherman, whose misfortune has turned to good luck. He can’t thank the captain enough. Nemo, however, refusing to accept his thanks, decides to give a gift to the poor, brave man. He presses a pouch full of pearls into his hand.

“Not only did you save his skin, you also gave him a whole new, affluent life,” says Aronnax with a mixture of amazement and admiration, but also a touch of indignation, as if the captain’s generosity has revealed some kind of inappropriate, tasteless ostentation.

“This Indian fisherman, professor, is a resident of an oppressed country, just like me,” replies Nemo.

“It’s hard to imagine you as an Indian,” says Land, his highly emotional state subsiding.

“Really?” The captain is surprised. “A long time ago, as a young sailor, I used to smuggle weapons for Indian insurgents fighting the English. I’m one of them.”

Part III: The man who wanted to be someone

The next stage of the journey takes the men to distant islands. When Nemo looks at their shores, he appears to be immersed in memories. He must be fond of them. First are the tiny, cold islets of Amsterdam and Saint-Paul in the Indian Ocean. Next, the hot, exotic Réunion. It is there that Aronnax learns from the sailors of the Nautilus (who are talking more and more boldly with their passenger-prisoners) about another episode in the captain’s life.

It turns out that, as an ordinary sailor, he once had a base in Réunion. He made a living there from smuggling and trading. Weapons, pearls, fabrics, Chinese porcelain, spices, opium – whatever he could. In the event of a pirate attack on his ship, he would light a cigar next to a powder keg, ready to blow up himself and his rivals.

Sailing under the French flag, he came across the forgotten islands of Amsterdam and Saint-Paul, and seized them officially on behalf of France. He built barracks, brought in labourers and whalers, amassed books, constructed a laboratory, and in his spare time he watched the penguins for hours on end. Sometimes, stray ships would arrive on the islands and the crews were surprised that anyone lived there. When the British made claims to these lands, the captain threatened to dig a trench there and defend himself – if not under the French flag, then under the Polish.

Hearing this story, the professor remembers the account described in the book of a certain Mr Verne of the children of the famous Captain Grant searching for their father over distant seas. They reached the island of Amsterdam and discovered that it was once run by a Polish-Frenchman. Aronnax has also read that these lands could be worth a lot of money as coal storages for steamboats travelling across the Indian Ocean.

Ultimately, however, the captain invested his money differently, in the thriving sugar plantations of Réunion. He settled there and married a French woman from the island. However, he lost his desire for the settled way of life when his beloved fell ill and died of the plague. Devastated, he struggled to find his place. Until, one day, news arrived from Europe: the Revolutions of 1848 had broken out!

The captain raised the money to set off to join the revolts in the Old Continent, where his brother was already fighting. They fought in Italy and in Germany, but the captain didn’t reach his native Poland – not then, nor 15 years later during the January Uprising. It was then that he decided to change the rules of the game – he would fight tyranny with terror. He faked his own death and commissioned a group of geniuses to design a submarine, paying them with the riches he had accumulated.

For every uprising against the great powers, he smuggled weapons to the insurgents. He also began to fight slave traders and refused to take any money that could have come from human trade.

Having heard all these stories, Aronnax somehow has the feeling that – contrary to his initial impression – Nemo is a wreck. He has spent his whole life battling powerlessness – both his own and others’. Battling the opposition and heartlessness of the world, and large-scale politics. Even his terror was anonymous, devoid of subjectivity. After all, with his super-ship, the captain disclosed nothing about himself, preferring to imitate a narwhal or sperm whale raging across the seas. What was he waiting for? What was he up to?

This impression stays with the professor, even when Nemo performs miracles over the next few months of their journey. He extracts treasures from the wrecks of sunken Spanish galleons transporting blood gold looted in the New World. He shows the men the underwater coal mines he founded. He sails to Antarctica and plants a red and white pennant embroidered with the letter N. And he doesn’t stop there – he also takes Aronnax and Land to the ruins of Atlantis he discovered…

But why do all this? Does he want to show off? Aronnax thinks things will become clear when the captain receives an urgent message off the coast of Europe from friendly Cretan insurgents. At that point, Nemo becomes even more excited. He looks like a hunter chasing game.

Part IV: Hunting the frigate

In late September 1868, the Nautilus is approaching the Scandinavian Peninsula. As they near Jutland, an alarm goes off on board. A war frigate with a red, white and blue flag with the cross of Saint Andrew has appeared on the horizon. Land quickly recognizes it as a Tsarist steamship, the pride of the Russian Navy. The ship’s name is Alexander Nevsky.

The mystery is no more. Nemo admits he has been tracking this frigate for a long time. He had learned from the Cretans that the tsar’s son, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich Romanov, was returning from Greece to Russia on board this ship.

It seems the captain’s mask is off.

“At last, I can take revenge on my tormentors. Those who cost me so many loved ones. Have you read the Book of Ezekiel? I have a favourite section…” he thunders. Then he begins frantically telling Aronnax about his father, a respected officer who died destitute. About his deceased mother, a Frenchwoman. About his brother, an insurgent leader in exile… And finally, about how, as a teenager, he took part in the November Uprising.

“It was a wonderful feeling when we could finally take revenge on the Russians.” The captain’s eyes are shining. “My brother wrote: ‘Can you hear the rockets hiss / Beating the Muscovites’ necks with a stick / The evil spirits won’t count Moscow’s corpses…’”

Nemo fought to the end. He was still defending Warsaw as the uprising was burning out. He stood by the cannon on the redoubt, ready to blow himself up. Wounded, he was taken prisoner. He managed to escape to the West, to France. There, he wandered the port streets of Nantes for days, dreaming of ships, long journeys and a better life. Until he finally became a sailor, trained as a captain, and grew up to be a man of action.

“A terrorist!” shouts Aronnax. What else could you call the planned attack on the Alexander Nevsky?

“Silence!” replies Nemo. “Let them defend themselves! It’s a warship!”

“Do you really want to sink this Russian ship because the Tsarevich is on board?” Land asks bleakly.

“And how!” replies the captain and gives the order for the attack to commence.

The Nautilus begins to gather speed. It trembles like a living beast. And finally, its spur pierces the tsarist frigate with a crack, like a needle puncturing a piece of linen. The captain is ecstatic.

The Alexander Nevsky begins to sink. Nemo and his crew watch in silence as their prey sinks into the depths. The hapless Russian sailors climb the masts and cling desperately to the sails, but their efforts are in vain. The Skagerrak strait will be their tomb.

Shaken up, Aronnax turns and retreats to his cabin without a word. Land, his face pale, simply shakes his head and follows the Frenchman.

Just a few hours later, they find out what happened next.

At the last moment, Nemo orders the submarine to ascend to the surface and approach the half-dead survivors. As they cling to the hull of the Nautilus, he tows them to the Danish coast. The European press will report that the Alexander Nevsky ran aground in an unfortunate accident, but the crew was saved, and the tsarevich emerged from the disaster unscathed. Nemo will remain a nobody.

It makes no sense for Aronnax and Land to continue their journey. There was supposed to be some sort of punch line, a grand finale, but… the captain orders them to be released at the earliest opportunity. Aronnax wants to say something uplifting to him before they leave, but he has no idea what. He too has a strange feeling of powerlessness. The Nautilus sails away towards Greenland. There’s still the North Pole to discover.

Professor Aronnax will spend several years searching for information on Captain Nemo and trying to discover his real name. All he finds is a dust-covered photograph in a Paris studio, and scrawled on the back: ‘Adam Piotr Mierosławski’.

Translated from the Polish by Kate Webster