Let’s imagine a world without imagination. Or that what remained at the bottom of Pandora’s box wasn’t Hope, but Imagination. The second version is easier to visualize because without imagination there can’t be any hope, either. Nor can there be plans for the future, readiness to rebel, inspiration to break old habits, the ability to bite off only as much as we can chew, and the desire to continue living, despite everything.

Let’s imagine… Imagine that! It’s unimaginable! It’s impossible to imagine! It’s beyond human imagination! These phrases have permanently entered our language, yet we never stop to think about what they mean. After all, they describe the crossing of boundaries between what is and what might be; between what surrounds us and what is in our minds; between reality and fantasy. The connections between the Polish word for imagination (wyobraźnia) and the word for freedom (wolność) aren’t entirely coincidental. Freedom without imagination is difficult to imagine. Similarly, there’s a close connection between the English words ‘imagination’ and ‘image’ – because it’s impossible to imagine anything in isolation from an image.

Imagination is the enemy of routine and the dread of dictators, pedants, bores, clergymen and conservatives. It’s the force that drives the world. Without it there would be no rebellions, social revolutions, scientific discoveries, distant voyages, romances breaking class divisions, games, entertainment, or enjoyment of life. There would be no art or literature. There would be no romantic comedies or horror movies. Visionaries would vanish from the world. There would be very little left.

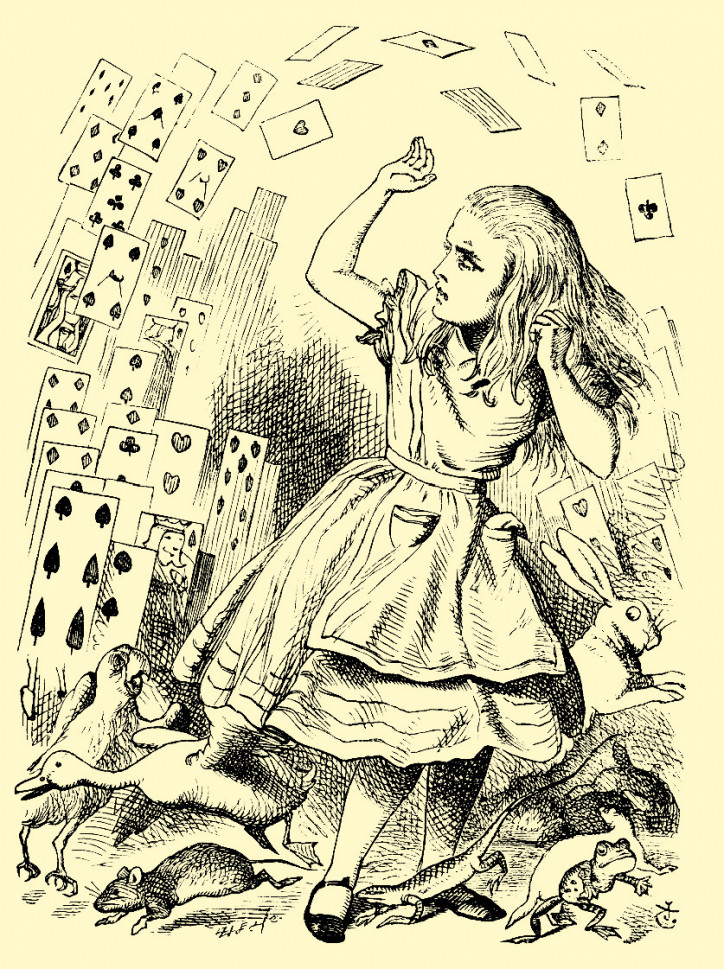

When she’s in Wonderland, Alice becomes so accustomed to unusual events that she finds ‘normal’ life boring and silly. She learns that adventures which undermine the familiar rules governing our world enhance the imagination. So she imagines, for example, herself vanishing like a burnt-out candle. Then she imagines what a flame looks like after a candle has been blown out. Lewis Carroll doesn’t describe exactly what Alice sees, thus stimulating our imaginations as well.

The Surrealists were honorary citizens of the Land of Imagination. Lewis Carroll was worshipped by Louis Aragon. In Carroll’s nonsense, Aragon perceived a revolt against Victorian morality; he pointed out parallels with Lautréamont’s The Songs of Maldoror and Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell. André Breton included “The Lobster Quadrille” in his Anthology of Black Humour. Alice in Wonderland has continued to inspire the surrealist