Every one of us can live a better life. With peace of mind, in the rhythm of the universe, and with a sense of order. We’ve known that for the past ninety-nine years. That is, since a certain Indian monk landed in Boston and infatuated a feverish America.

The “City of Sparta” was the first ship to sail from Bombay to Boston after World War I. It left in the summer of 1920, with a cargo of jute and tea, along with sixty-one passengers. They included British students, missionaries, businessmen, tourists, two Armenians rescued from the genocide in Turkey, and eleven Hindus. One of them was a man with long hair dressed in a traditional, ochre-coloured outfit. His name, Mukunda Lal Ghosh, was entered into the passenger list along with an incorrect date of birth. At the time, he was twenty-seven, not twenty-five, as the officer had hammered out on the typewriter. The “Profession” column had quite an intriguing entry: “governing brahmin” (although he was born into the kshatriya, the military caste), and next to it a handwritten note: “professor.” One more category was also added: “English-speaking subject of the British Queen.” His nationality, “Bengali,” was crossed out and corrected to “Eastern Hindu.” The following information was also noted: “Not liberal, save in matters of religion”.

This seems logical enough, as he was on his way to the Congress of Religious Liberals as the official representative of Hinduism.

The Swami from India

From these few little peculiarities, it’s easy to understand how for the Euro-Atlantic world, with its tables and definitions, Mukunda was an issue from the very start. Indeed, to this day, we have not been able to fully express in our own words (and this text will be no exception) who this Indian pilgrim was who had come with the mission of building a bridge between the East and West. Such a fusion seems quite natural in this day and age. It could even be perceived as a trivial, well-travelled path that Europeans and Americans follow to the numerous yoga and meditation centers in moments of metaphysical doubt and personal crisis. But 100 years ago, the thought of a global teaching of awakening the mind and aligning the body with the energy of the cosmos was a pioneering move for us; one that required courage.

The idea emanated in times when India was deeply divided by a caste hierarchy and socially conflicted by the colonial rule of ‘divide and conquer’, Europe was falling into fascist madness, while in America racial prejudice was the order of the day and the Ku Klux Klan marched in its streets. A common model of thinking was popular on both sides of the Atlantic, which Rudyard Kipling expressed in a single sentence: “East is East, and West is West”.

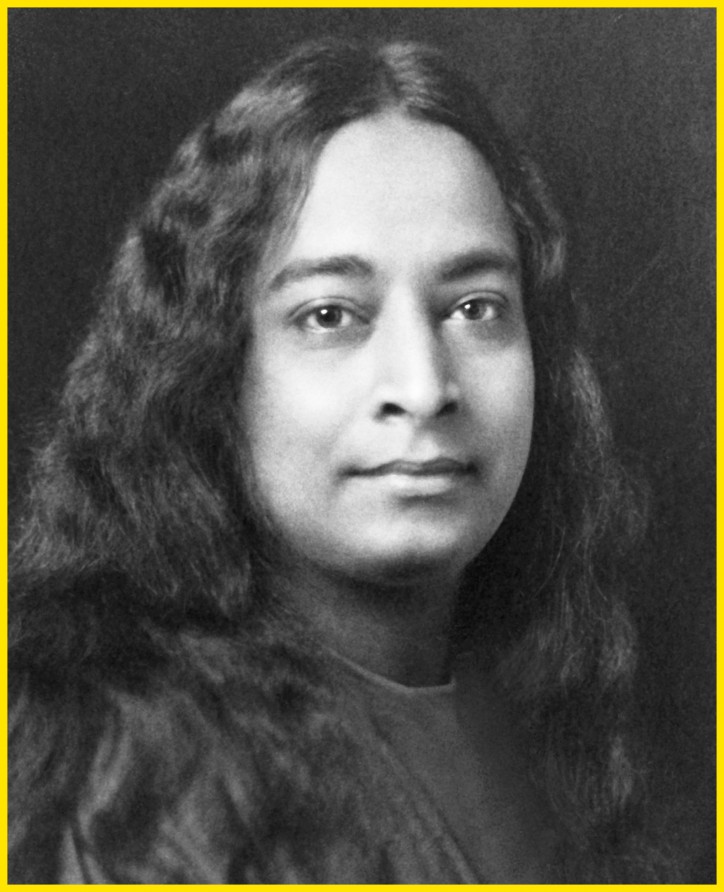

After forty-eight days at sea, each one spent with a feeling of solitude and general “unknowningness,” Mukunda entered the port in Boston. A photojournalist from the Boston Globe photographed the newcomer. The black-and-white photo appeared on September 20, 1920 on page seven of the paper. It portrayed a man—his body wrapped in robes and an impressive turban on his head—wearing specially tied knee socks and leather Oxford shoes, with long hair, but a clean-shaven face. He had gotten rid of his beard on the ship, most likely on the advice of fellow passengers, who knew what a sensation he would be even without it. On the photo, Mukunda has a gentle smile. Below the photo was a caption: “The Swami from India.”

“Swami” is an honourable title for a clergyman, the equivalent of a monk, although in Hinduism, being a monk does not necessarily mean spending your life in a formal monastery (just like there are no institutionalized Hindu churches). Rather, it means being a member of a line of clergymen, being obedient to many generations of gurus and their teachings, as well as leading a life in spiritual discipline, accompanied by sacrifices and moral obligations. In other words, pursuing a spiritual mission without the supervision of a religious organization.

The Swami won the hearts of reporters by greeting them in fluent English. There wouldn’t be anything terribly strange in this (many Hindus studied at colleges established by the British), if it weren’t for the fact that, many years later, Mukunda claimed that he actually did not know a word of English when he boarded the ship. In the book The Autobiography of a Yogi, he writes that when he was asked to present a lecture for his fellow passengers, he was so stressed at first that he couldn’t say a thing. To his aid came a vision of his guru Sri Yukteswar, whose call, only heard by Mukunda, was: “Speak!” That’s how the monk, overcome by linguistic complexes, would in that brief moment become a seasoned speaker. This was one of the events that he would later refer to as a miracle. Likewise, he considered as an act of higher force the fact that he had received the invitation to the congress in Boston from an Indian clergyman whom he had met by accident and who, as it turned out, could not go himself. While still on board the ship, Mukunda collected a handful of business cards and invitations to speak in various American cities.

He stayed at the YMCA on Huntington Avenue, rode the subway with zeal, and carefully selected his meals in the cafeteria to suit his vegetarian diet. At the beginning, he kept to bread and milk. He would walk around, full of curiosity, yet he experienced hostility right away. He would be stared at, ridiculed and insulted, and various objects would be thrown at him. Once some girls in a street car tugged at his hair, thinking he was dressed up for Halloween. To give himself a break, he would sometimes wear European clothes and pull his hair back.

Although no notes have been found to confirm this, colliding with a world in which diversity fuelled prejudice must have been a shock for him. Mukunda came to America from India. Even though it was economically stratified, full of poverty and ever strongly immersed in the Hindu-Muslim conflict, India was a country that respected diversity. On the shores of the Ganges, the multitude of lifestyles did not cause controversy, as the co-existence of contradictions is the essence of Hinduism.

He came to the West with that very message: of unity as the essence of life manifested in many ways. The US was a young nation molded from people representing a variety of communities, beliefs, and cultures. They were only just beginning to experiment with equality and giving others the right to co-exist in freedom. Meanwhile, Mukunda was representing a tradition spanning thousands of years. One that preaches an understanding of one God, but a God that does not exclude anyone or anything. He is everything and everywhere, in every single person.

One God

That was also what he spoke about at the Congress of Religious Liberals. Instead of presenting a set of dogmas, he conveyed universal ideas that he referred to as the “science of the soul”. The scientific approach was an important element of his speeches, and was the terminology he would use while working in the US and other countries over the next three decades. On the one hand, he understood the esteem that knowledge had been enjoying in the West since the period of the Enlightenment. He was well versed in biology, anatomy and physiotherapy, and was up to speed on the latest findings in physics, as well as the fledgling realm of psychology.

On the other hand, though, he proposed a different understanding of science. For followers of Hinduism—or from a wider perspective, the philosophy of the East—that which was experienced was considered to be the truth, rather than what could be rationally confirmed. So if we assume that religion is the awareness of the presence of God, then, Mukunda argued, there is only one religion and one God. The young monk suggested that reality should be perceived as a Maya (or a multicoloured illusion); a type of shimmering cloth which masks the truth that energy is the only thing that exists.

The truths that he was declaring fell upon a certain “moment of peculiarity,” or the intellectual acceleration at the beginning of the roaring 1920s. While any deliberations concerning energy could have been easily rejected just a moment earlier, the development of physics, Einstein’s research, and the discovery that the world is in fact made up of atoms—which are both matter and energy at the same time and are constantly in motion and under tension—led to a stunning coupling effect. The old truths of the East began to take on the form of proven scientific evidence in the West. An opportunity appeared for these notions to meet, though they were conveyed using different languages.

This tendency affected not only ordinary people, for whom the finale of the Belle Époque—which had been suffocating on poisonous gas and drowning in rotting trenches—became an impetus that forced them to redesign their thinking, and redirected them onto the path of exploration. An encounter of Eastern and Western philosophy was being observed at the highest level of thought as well. Carl Gustav Jung wrote that the East had much to offer for people in a mentally-shattered Europe, and indeed saw an opportunity in linking scientific notions with knowledge of the soul. Albert Einstein was close friends with Rabindranath Tagore—the ‘Bengali da Vinci’, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, an ingenious poet, singer and thinker. He founded a pioneering university in India that merged scientific thought from both sides of the world. To this day at Shantiniketan, the school of free thinking situated in a village near Kolkata, students indulge in a mix of academic knowledge and physical and spiritual activity, all this while in the open air, in the shade of trees, with a healthy posture and full awareness of their breathing.

Mukunda met Tagor (they had in fact lived close to each other in northern Kolkata) in New York’s intellectual Greenwich Village, full of yogis, artists and singers. Mukunda was a child of the Bengali renaissance—an artistic awakening that came to be in the area of Kolkata (former Calcutta, the capital of British India, and also the most important intellectual center on the subcontinent), spanning the spiritual sphere, education, culture and language, as well as social liberation. It created a base that would challenge the caste hierarchy and call for the recognition of Indian cultures as equal and in co-existence with other intellectual trends in the world.

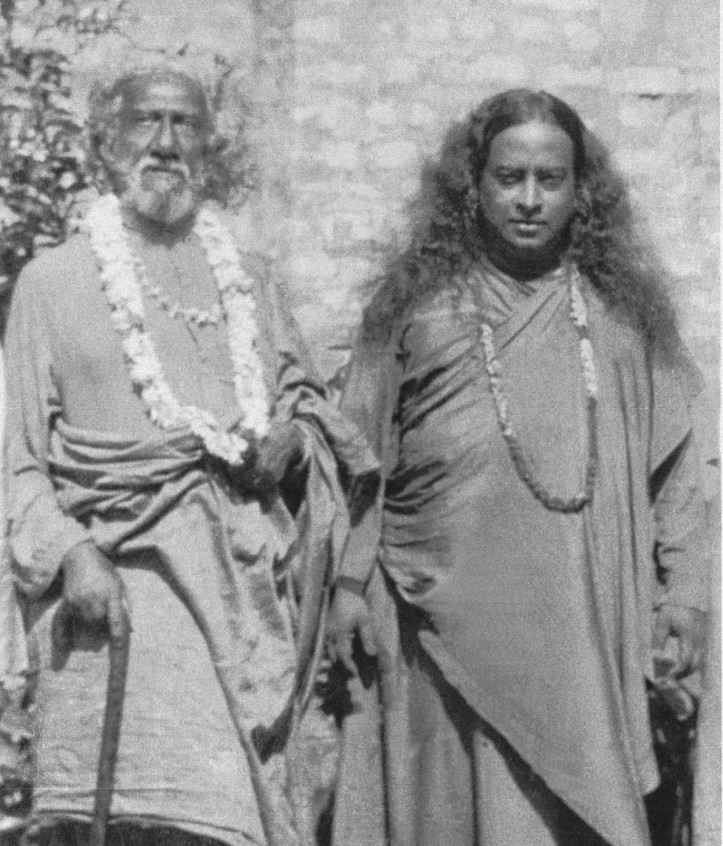

It was this very prophecy—creating the link between the spiritual East and the material-anchored West—that Mukunda’s spiritual gurus, Sri Yukteswar in Varanasi and his other deceased masters, had instilled in him. It was them that the young monk was supposed to have seen in his visions as shining figures speaking to him. He was their missionary in America, a land flung into a frenzy of rampant growth and reckless investing and buying, yet seeking salvation.

Prohibition was introduced in the US, and illegal clubs blossomed where jazz was played and the Charleston was danced. Cities were marked by their constant rush and the relentless quest for money. Manhattan and Chicago were climbing higher thanks to state-of-the-art technology: structural steel, elevators and electricity. ‘The sky is the limit’ was the motto of those days—indeed, ambitions and dreams knew no bounds. A spirit of mobility was in the air, as automobiles and telephones opened the door to travel, communication and transactions on a scale unheard of before. Imposing fortunes were growing. A new sexuality, fashion and art were erupting. Women could vote or go to psychoanalysis sessions, and anybody could earn money and believe in what they wanted. Appearing right in the middle of this resonant melting pot was a Hindu yogi calling for the complete opposite. He would say: “Where motion stops, God enters.”

The Super Guru

Many years later, the Los Angeles Times declared Mukunda, known to the world by his holy name of Paramahansa Yogananda, as the first celebrity Super Guru of the 20th century. You can just imagine the gentle smile with which the spiritual master responded to such recognition. But he wouldn’t have earned that nickname if he hadn’t put so much hard work into it. As the first guru and yogi, he created a global empire of followers, a type of matrix for those who followed, like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and the transcendental meditation movement, or the Ramakrishna movement, which started off low-key but then gained in popularity. Yogananda was the first to establish a network of spiritual improvement centers, courses, correspondence study programmes, and publications. To this day, people in 175 countries practice his teachings. There are around five hundred centers modeled on the ones he founded one hundred years ago in Ranchi, India and Mount Washington, New Hampshire. How did he achieve that?

In addition to a scientific perspective—the language of reason and research—Yogananda consistently applied other approaches, which made it easier for people of the West to look at him as a common-sense authority, and not one of those scammers who had been filling lecture halls and newspaper ads since the Great War. Namely, the Indian monk talked a lot about Christ. He tried to promote the ‘original Christianity’, or the early ideals that accompanied the followers of Christ when they were a young sect. These included equality, brotherhood, Jesus as the son of God (and therefore the unity of humans with God).

One of the ideals of Hinduism that is most difficult to convey is the aspect of full acceptance. While other monotheistic religions have an exclusionary character (“Thou shalt have no other gods before me . . .”, “There is no god but Allah . . .”), Hinduism does not pay too much attention to religious form and practice. In fact, its followers can choose among their favourite gods. For example, Yogananda’s family held Kali in high veneration. Kali was a good-natured, though violent goddess who fought off demons. In private rooms of prayer or on altars you will quite often find the Hindu Vishnu, Krishna, Ganesh or Saraswati. Set right next to them are figures of Buddha, Christ and . . . Bollywood stars. Yogananda believed that John the Baptist was the guru and spiritual teacher of Jesus, as well as the reincarnation of Elijah the Prophet.

What is considered in the West as sacrilegious or superstitious is accepted by Hinduism as one of the ways of understanding God. If people need His image – if it is easier for them to glorify the Spirit in the form of prophets or divinities – Hinduism has no issue with that. According to many Hindu schools of equal footing, there are a number of different paths to God, such as philosophical contemplation, spiritual sacrifices, yoga or deeds. Hinduism is the quintessence of freedom in our pursuit of the truth about the universe and our role in it. It perceives God as an ocean, while we are the waves submerged in it. Yet that particular perception of freedom still proves to be too wide of a proposal for many Westerners. It is still easy to reject as an ‘all meaning nothing’ offer. At the same time, we find it hard to accept that reality, the meticulously created material and emotional layer could be… without meaning.

A New Theology

But let’s come back down to Earth, or rather, the US earth in 1920. Yogananda was breaking new ground with his work. With the help of his first allies and students, he organized small meetings in Boston in the form of lectures. They were held in conference rooms where a handful of attendees would appear. For the next three years, the spiritual leader would live here and there—people would take him in, or he would stay at boarding houses.

He carefully listened to his surroundings and recognized the meaning of information, advertisement and money. His first ads appeared in newspapers, on the radio and on posters. In the press, he was usually classified in the ‘Variety’ or ‘New Theology’ section, along with ads about burlesques, vaudeville shows, film screenings or esoteric meetings. He would be introduced as an Indian clergyman, but also as a “famous psychologist and educator from Kolkata”. He would manage to organize weekly meetings, have open lectures on Saturdays at 7:45 pm, give lessons to interested students, and present physical and mental exercises for a small fee. The subject area of the lectures shows quite clearly that Yogananda fell into an interdisciplinary niche for which finding the adequate language was difficult. So he would talk about the “Law of Karma and Fate,” teach “How to Control Your Life Forces,” present the “Psychology of Success,” or discuss the “Spiritual Christmas.” He used terminology that bordered on spirituality, faith, and something that we refer to today as “coaching.”

Yogananda specialized in Kriya Yoga, an approach that concentrates on the ability to consciously control energy, or more precisely, the flow of energy in the body, up and down along the spinal cord. Yogananda remained loyal to the eight basic rules of yoga defined by the mythical guru Patanjali, who described yoga as life with a specific moral attitude combined with physical activity, which teaches you how to unite your body and soul, experience deep states of meditation, and experience a bond with all existence and God. Yogananda would direct the focus to energy “management.” A set of exercises and practices that he had put together in India and popularized under the name of Yogoda would teach people how to fuel their bodies with energy taken from the environment and beyond by tensing and relaxing their muscles while consciously controlling their breathing.

This spiritual/physical activity was an element that would liberate people from the common Western conviction that the body and soul are separate. The act of recognizing the unity of the two, and experiencing the feeling that they are one, was the first step towards a much greater challenge: acknowledging the unity of the universe. The first American adept in Kriya Yoga was a doctor working in Boston, Minott Lewis, who had met Yogananda in a church on Christmas Eve, and experienced something that many of his students would talk or write about later. In the eyes of the guru, Lewis saw a kind of shining energy that he wanted to surrender himself to right then and there. That very evening, he declared that he would follow his spiritual master. In the months and years to come, the number of Yogananda’s students and loyal companions would grow.

He gave his first big lecture in the spring of 1921 in the auditorium of a music conservatory. Crowds piled in even though that same evening, Toscanini was conducting the La Scala orchestra at the Boston Philharmonic next door. The first investment was made in 1922, when Alice Hasey donated a small plot of land and seasonal building in the town of Waltham, which meant that regular spiritual sessions could be organized in the outdoors. Hasey was the first in a long line of women who were exceptionally devoted to Yogananda, and who would donate small or quite impressive sums to his operation, additionally helping in the management of the centers. In 1922, Yogananda gained a key assistant. His close friend and companion in spiritual practice from his younger years, Dhirananda, sailed in from Kolkata. He would be his right-hand man for fifteen years, managing the educational centers as well as the lecture tours spanning thousands of kilometers. He would remain a key associate until a scandal erupted, in which Dhirananda was accused of promiscuity and relations with married women, meaning that, in effect, Yogananda himself was accused of leading a spiritual harem. His right-hand man would all of a sudden demand compensation for years of missionary work, taking his master to court (though, as it turned out, Dhirananda had in fact misused enormous sums of money). After all of this, he would eventually return to India, get married, and set off on an academic career.

Self-Realization

The popularity of Yogananda, an excellent speaker who knew how to use informal language and effectively combine it with old-fashioned concepts, and who with time enhanced his appearances with songs and music, was rapidly growing. Already in 1923, he was invited to give a series of lectures in New York. There, he applied a simple business model, which he would use for many years to come. His lectures were open, but the lessons would cost a fee. He would distribute brochures with an introduction to the basic assumptions of Kriya Yoga, but only students at higher levels of advancement would discover all its secrets. Yogananda started to publish books with prayers, instructions on concentration techniques, meditation and breathing, as well as ‘energizing exercises’, poems and songs. He quickly became popular among the Manhattan elite, and won them over by adapting the terminology and complexity of the exercises to the capabilities of his adepts.

He was criticized for this. In the US and India, he was accused of cynical and commercial behaviour, as well as of “vulgarizing yoga”. Yogananda defended himself by consistently maintaining that his operations were not making anybody wealthy. A few years later, the activity was formalized as a non-profit organization. The role of the Self-Realization Fellowship was to promote Kriya Yoga, and the philosophy and exercises prepared by Yogananda. The master also transferred the rights to all his works to the fellowship. This included above all his autobiography, which is considered to be one of the most important and most popular books on spirituality of all time.

The Autobiography of a Yogi sold millions of copies in over fifty languages and contributed to the popularization of Yogananda’s thoughts more than thousands of his lectures ever did. He published the autobiography in 1946, just as America was emerging from the post-World War II crisis. Increasingly, more money was being accumulated, and along with it, growing faith in the future, with many people yearning for inner revitalization. Two decades from its first release, the yogi’s autobiography – which was written in an approachable manner and initially planned as a description of saints and inspiring people whom Yogananda had met throughout his life – fit the bill for the needs of the young counterculture generation, appalled by the war in Vietnam and seeking a new morality. George Harrison had a stack of these books at home; he would pass them out to guests, saying each time that if it weren’t for Yogananda, he would be dead. Steve Jobs constantly read the book all through his life. Each person that came to the funeral of the technological guru in 2011 received a small black box that held a copy of the Autobiography of a Yogi.

The book contains descriptions of over 140 miraculous events. It is quite legitimately referred to as “the book that changed the lives of millions.”

The gains from the autobiography supported the Fellowship. However, throughout most of his spiritual career, Yogananda had financial problems. He would take out loans and be late with payments. Although he was a recognized clergyman, signing the book contract took him over a year. In addition, the author had to buy out half of the edition himself.

Throughout the years, the balance on his bank account never exceeded $200. From the time he came to the US until the mid-1930s— the very bottom of the Great Depression, when nobody had a single cent for spiritual development—the guru constantly travelled. He lectured, he taught, he wrote. In the mid-1920s, together with his Muslim secretary Mohammed Rashid, he drove almost five thousand kilometers from the east coast to teach in California. They went through the so-called Bible Belt—the conservative central and southern states. Accompanying them on their trip were two white students, whose presence was supposed to protect them from any possible racist attacks.

In Los Angeles, Yogananda found quite an audience. He called it the American Varanasi, or the “center of spirituality,” where no idea was too radical and where everything that was strange was openly embraced.

It was also there that he settled down in the second half of the 1940s, near San Diego, setting up his retreat—a small room with a sprawling and spectacular view of the Pacific. Thanks to the generosity of his students, a spiritual center was built there (a monastery for women was also established) alongside a church of All Religions. In the later period of his life, when he travelled and spoke publicly much less frequently, he became very fertile in his writing. He worked on a collection of motivational letters, songs, and a second important book called Whispers from Eternity, which was a volume of clarifications, prayers, and his spiritual credo.

He died in 1952, the same way as he had lived: consciously. From the reports of witnesses and biographers, we know that he felt quite precisely that his time had come—he spoke of it on the morning of his death. His condition was clearly worse, he had trouble moving, but he did manage to make it to a meeting with Indian diplomats and the Indian ambassador visiting California. He was on stage reciting a poem about his love for India when he suddenly collapsed and fell. The official cause of death was cardiac arrest.

He departed from this world, leaving behind a lively and widespread institution, which took on a shape more formalized than the monastery that he had joined as a mere 19-year-old boy, stubborn and independent. He quickly understood that nowadays “even the truth needs to move around in an organized manner”. He educated his apprentices, so he himself could gradually withdraw from any contact with his surroundings. In that aspect, he was very much like his father, who after the untimely death of his wife when Mukunda was only a few years old, focused on Kriya Yoga. After work, he would lock himself up for hours on end and deeply meditate in solitude.

Retreats in the Himalayas

Having possibly been strongly influenced by that model, the future five-year-old Yogananda would perform pujas (or prayer sacrifices). He would then meditate in the storeroom on the roof of his house in Kolkata, indifferent to the merciless heat and monsoon rains. Together with his friends, he set up the first Ashram (or spiritual center) in the arbour of a messy property in his neighbourhood.

He didn’t care about school. The only thing that forced him to finish elementary school, high school and college were the orders given by his father, and guru Sri Yukteswar. He was seldom present in class and got bored quickly, although he was mathematically talented, wrote poetry, was a great runner and played team sports. After school, he preferred to spend time on the banks of the Hooghly River, a branch of the Ganges, among the old gurus, whom he would ask never-ending questions. Then, after several hours of cleansing baths, he would walk along the edge, naked and buried in thought, until some outraged woman or shopkeeper would yell at him to cover himself up.

Even as a boy, he wanted to be a monk. His mother supported his dream. She had visions, believing that Mukunda survived the difficult birth thanks to the intervention of her guru. He gave her son a medallion, which, as she claimed, miraculously materialized in her hand. His father was less enthusiastic, and together with his older sons, tried to direct Mukunda onto the path of a bureaucratic family career. They would interrupt his arbitrary quests into the Himalayas, where he had intended to live in sacrifice among the sadhu, the pilgrimage sages. His brother would catch him at train stations or on trains, and take him back home.

Finally, his father gave in, giving Mukunda his blessing to become a swami. He let him leave for the monastery in Varanasi. He supported his son when he opened the first school of spiritual learning in Ranchi, which still operates to this day. In 1920, it was his father, a high-ranking employee of the British Indian railways, who helped him get a passport in a surprisingly short time and paid for a first-class cabin, suddenly made available by a certain passenger, on the ‘City of Sparta’ for the man in a bright turban.

When in 1935, Paramahansa Yogananda returned to India for the one and only time, he spent a year there, travelling in a Ford he had brought over from the US, visiting his beloved places as well as teaching. Everywhere he went, he was greeted by crowds of people who would decorate him with garlands. He enjoyed the status of a live saint, worshipped in a way usually reserved for divine beings. The only person he would now bow down to, brushing the dust off his feet with devotion, was his father.

***

The memorial service after the death of Yogananda, according to whom faith was only a passage and a transition, took place on Mount Washington. During the ceremony, the body of the yogi was displayed in an open coffin, causing a wave of reports that he looked like a young boy. Music was played, and the ceremony was half Hindu, half Christian. Quotes from the Bible, the Vedas and the writings of Mahatma Gandhi were read. His remains are interred in the mausoleum of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park cemetery in Glendale, California.

My sources included the following books: Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda (trans. Wojciech Szczepkowski, Zabrze 2009), The Life of Yogananda: The Story of the Yogi Who Became the First Modern Guru by Philip Goldberg (Hay House, Portland 2018), Whispers from Eternity by Paramahansa Yogananda (trans. Zbigniew Płoszczyca, Gdynia 2016), and collected works published in a series called The Wisdom of Yogananda (Gdynia 2016–2018).