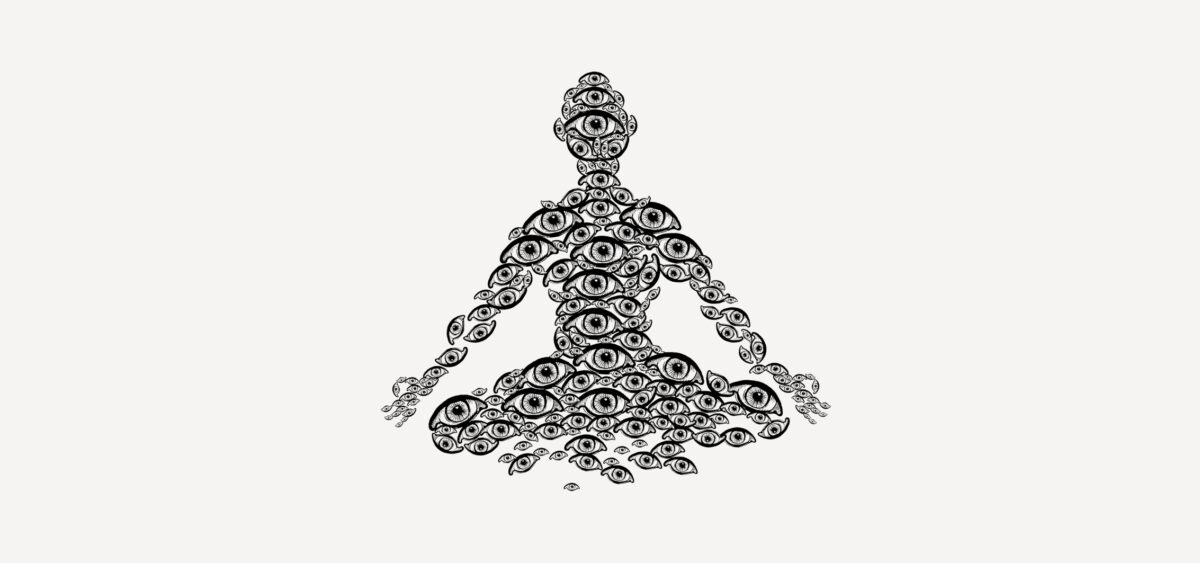

According to Wikipedia, there are over 40 types of meditation. The majority of them have been proven to enhance physical health, the psyche, and even the function and structure of the brain. Contrary to the stereotype, meditation doesn’t need to have anything in common with religion or faith (but, of course, it can).

“Mantra? But really, what’s the difference between that and my patients who keep repeating shit, shit, shit over and over again?” was the question a certain outstanding and esteemed clinical psychologist from Harvard University asked when a young Daniel Goleman presented his idea for a PhD thesis to a group of professors. The title was “The Effect of Meditation on the Mind”. This also included meditation based on a mantra, or a technique involving the constant repetition of a word or phrase.

It was the beginning of the 1970s. In spite of the variety of subversive and extravagant ideas bubbling beyond university walls (as the counterculture was at its prime), behaviourism – the conviction that humans are organisms that one can reasonably speak of only from the perspective of their behaviour – prevailed in academic psychology

The inner experience? An intimate feeling of subjectivity? There is no such