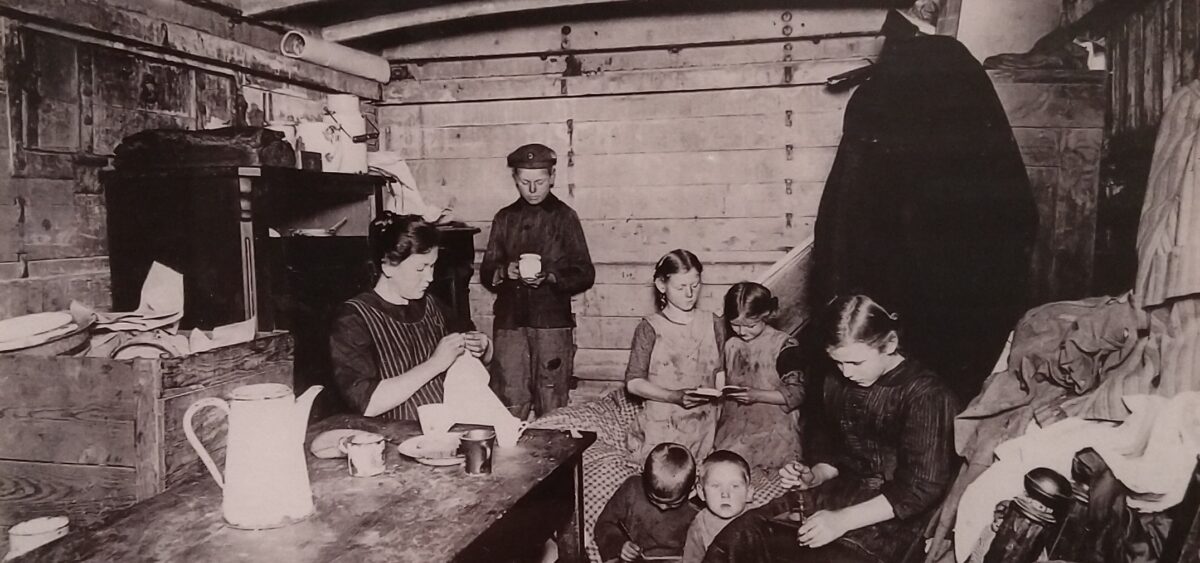

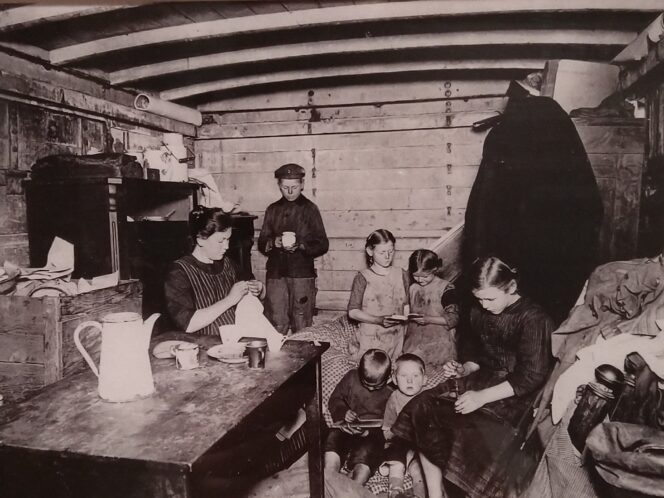

The testimony to the interwar era presented at the recent Kraków exhibition More Than Bauhaus is difficult to accept. In addition to people, the photos portray poverty, hunger, emaciation. And simultaneously, we the viewers know well that the world presented in these photos will disappear in a moment. This essay about three similar photos, which nevertheless differ significantly, was written for “Przekrój” by Wojciech Nowicki.

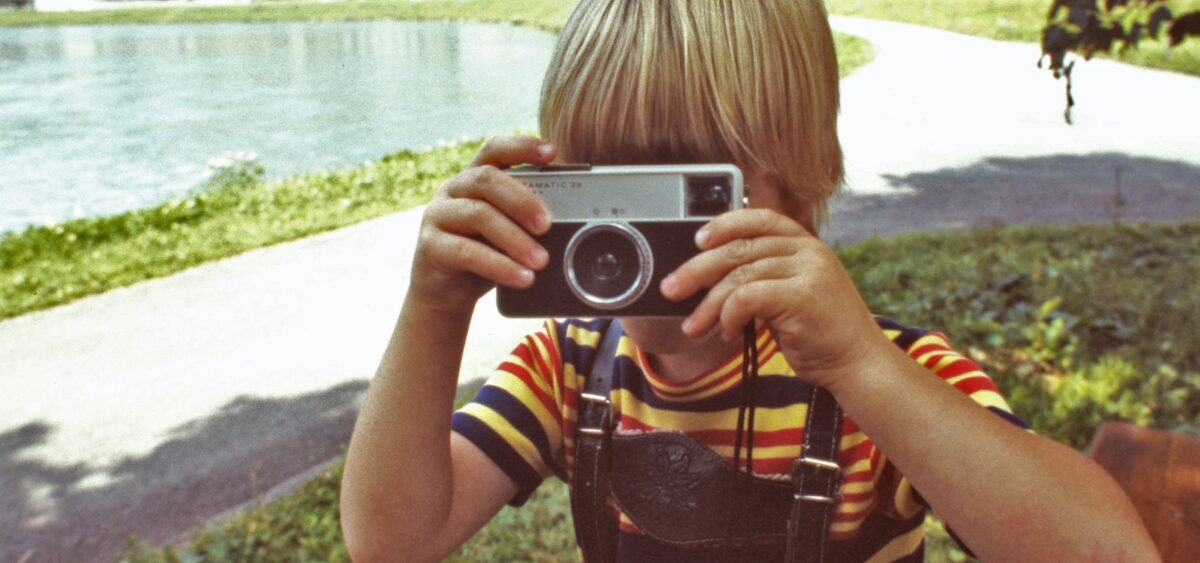

I have here three photos; I saw small prints of them at the exhibition. They were easy to miss. The first two might be by the same photographer, but that’s just an assumption. From the same period, on the same topic: the effects of the Great Depression in 1929–1933 in Germany. The third photo can easily be grouped with the first two, because it’s about a crisis in the same land – but here it’s a different crisis. Not a global one, but an internal, German one, an earlier one. It’s from 1920.

All of the photos, occupying the space between reportage and documentary, were created in the years when press photography didn’t worry about photographers’ names: the person with the camera was just an ordinary piece of equipment. An arduous, neverending job, but also an opportunity for work and pay. During times of poverty, they photograph people suffering poverty, but they do it from the position of people who still