Wassily Kandinsky studied to be a lawyer, but instead became an artist. The biggest break in his life came when he understood that even when art does not mimic objects, it remains saturated with spirituality.

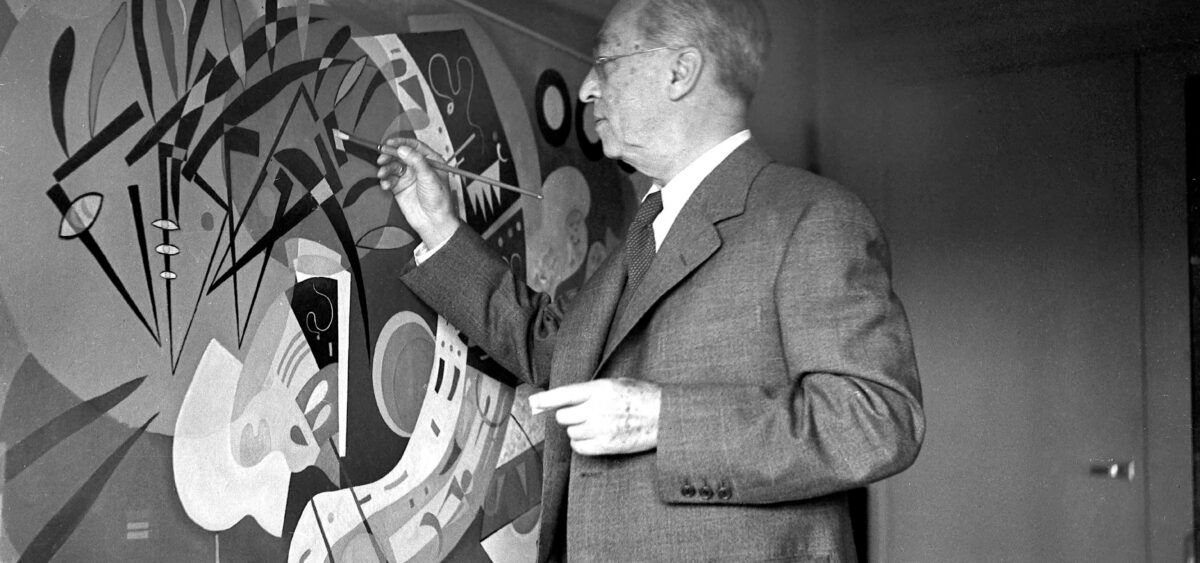

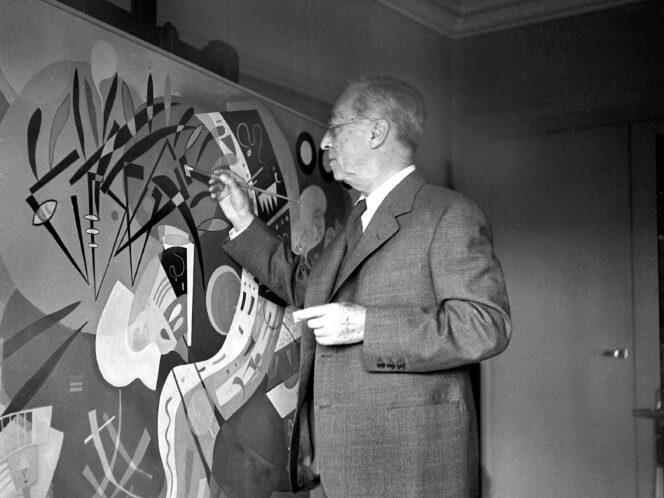

Kandinsky’s coffin went on display in the artist’s atelier. Nina, his widow, fulfilled the Orthodox rite. By the coffin, instead of an icon, she placed her husband’s final great composition – the painting Reciprocal Accords. It was created two years earlier, in 1942, amid the turmoil of war, and features biomorphic shapes and cool colours, enamel-like smoothness and lustre. Nothing on this canvas indicates unrest or a state of emergency. Following years of painting dramatic scenes, conflict and struggle, often conveyed by the contracting of light and shade, strong colours and directional tensions, Kandinsky’s art softened, as he apparently reached a state of inner peace and harmony. After all, he always claimed that a painting is a reflection of one’s soul and a gateway to transcendence. “Whatever I might say about myself or my pictures can touch the pure artistic meaning only superficially. The observer must learn to look at the picture as a graphic representation of a mood and not as a representation of objects.”

The birth of an artist

The father of abstract art forged the new path in painting slowly, with difficulty and caution. He combined painterly ardour with the frostiness of an art theorist. He believed that art was directly subordinate to cosmic forces. Following the Russian theologian and poet Vladimir Solovyov , Kandinsky criticized the