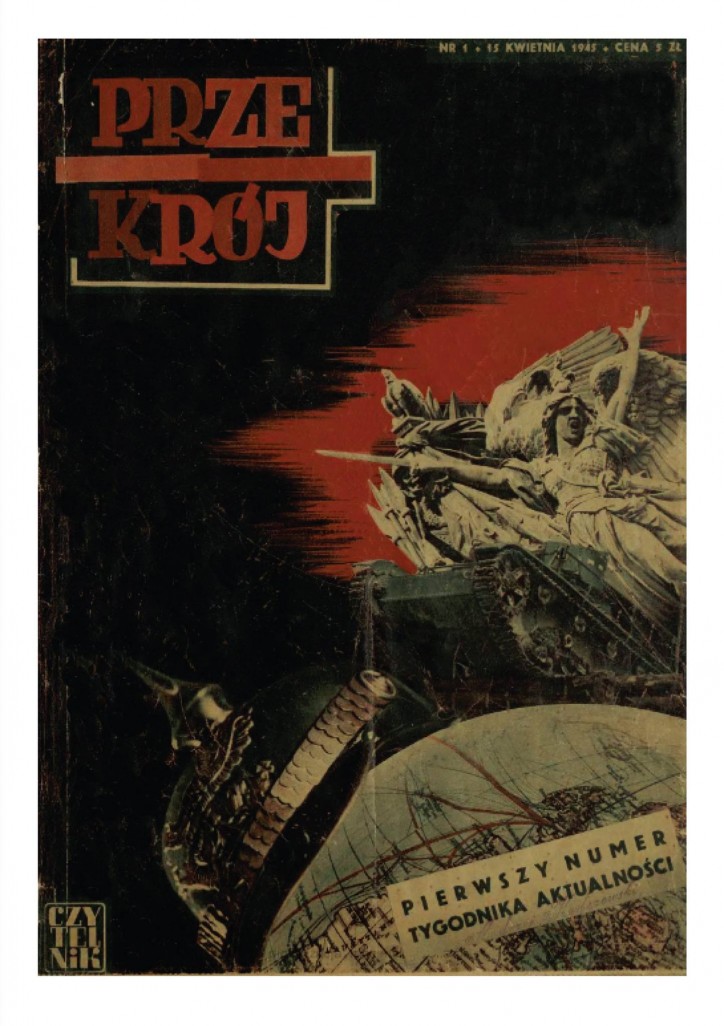

The cover shown here belongs to the first issue of Przekrój, which appeared on April 15, 1945––before the end of the Second World War. At the time, the future of the magazine was uncertain.

The designer of this cover and the overall look of Przekrój was Janusz Maria Brzeski, the artist who popularized the collage technique in Poland.

The term “collage” was used in China as early as 200 BCE, but only appeared in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. The cubists Georges Braque, and slightly later, Pablo Picasso, were the first to use it––one of Picasso’s famous early collages is