An acacia branch, a rope, a skull, a compass, a square – every symbol depicted on a Masonic artefact serves to remind its owner about the duties of a lodge member and the knowledge they have acquired in arcane rituals.

Contrary to popular opinion, Masonic lodges are not secret organizations – although Masonic rituals are certainly shrouded in mystery. Their secretive character is a key factor in the selection of props used by brotherhood members. Apart from symbolic emblems, such as aprons, sashes or gloves, the society’s customs are enriched by extraordinary regalia: Masonic jewellery.

The word ‘mason’ is an occupational name for someone who works with stone. The name of the fraternal organization is also tied to its founding myth. The principle figure in this story is the architect Hiram Abiff, who was delegated by his namesake, the ruler of the Phoenician city of Tyre, to watch over the construction of King Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. Abiff was a Freemason, the only man alive who knew the Grand Masonic Word – the most important secret of the Master Mason. He promised to reveal it to his disciples after the completion of the temple. However, the impatient apprentices decided to force his hand earlier, and murdered the Master when he refused. The rest of the myth describes King Solomon himself resurrecting Hiram. Once the architect returned to the living, he allegedly revealed the Secret of the Masonic Master in the first word he pronounced – passed on to his successors to this day.

Freemasonry, sometimes called a royal art by its followers, is organized into fraternities or lodges (from Old French, ‘arbour’ or ‘hut’). It first became active in England and Scotland at the turn of the 17th century.

It was a chaotic time in the history of the British Isles. King Charles I was executed at the beginning of the third civil war, Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth and his dictatorship deepened the existing divides. The restoration of the Stuart dynasty after Cromwell’s death did not last long. During the so-called Glorious Revolution, the English Parliament declared war against Jacob II and forced him to flee the country. The coup was driven by the Parliamentarians’ fear of royal dominion and the risk of Catholicism being reinstated as official religion. However, it must be said that the Protestant majority not only controlled, but also persecuted Catholics. This religious and political turmoil gave birth to Freemasonry.

The main goal of the first Freemasons was to reconcile the two fatally conflicted religions. Soon enough, they became engaged in solving the social problems of modernization, as well as establishing dialogue between the old and the new elites.

Neither contemporary nor historical Freemasons functioned in uniform organizations. Freemasonry was always a movement that relied on ethics. It was developed through symbols and allegories and promotes its own conception of man and society, based on a set of principles Freemasons consider crucial. Various fraternities developed different ceremonies, symbols and rituals that resemble religious mores in some ways – and also rely on ceremonial clothes, props, allegories and symbolism. As a whole, Masonic practices share one common feature – they depend upon a secret initiation ritual.

The discreet character of Masonic rituals may have influenced the society’s black legend. The most frequent accusation brought against it was its secretive activity, which of course had to mean that Freemasons were driven by unholy intentions. The fact that Masonic principles clearly promote tolerance and encourage members to care for their own self-development (and nurture that of others) did not help.

Although the Protestant church was generally favourable towards Freemasons, they did not enjoy Christian support. Almost 21 years after the first Grand Lodge opened, Pope Clement XII decided to compromise the activity of the organization. He published the papal bull In eminenti apostolatus specula and forbid Christian followers from joining lodges under threat of excommunication. He gave three arguments: first, Freemasons kept numerous secrets; second, they dared to claim all men were created equal; and third, most important, those liber muratori had the gall to act as if all religions were equally worthy. Of course, the pope’s efforts did not cause the demise of Freemasonry, but his claims must have worsened the widespread belief in Masonic conspiracy.

Keeping Masonic secrets was mostly possible due to the language of symbols used by the society’s members. Lodges would often borrow symbols from various chivalric orders, with alchemist iconography being an important source as well. However, the vast majority of Masonic terminology was inspired by the work and rituals of ancient architects. Depictions of the compass, the trowel or the square (a tool used to measure right angles) are among the most popular Masonic emblems. Their original meaning changed during the Enlightenment, becoming more complex and better suited to a given lodge. The meaning encoded in symbols is an important addition to Masonic artefacts.

Mysterious jewellery

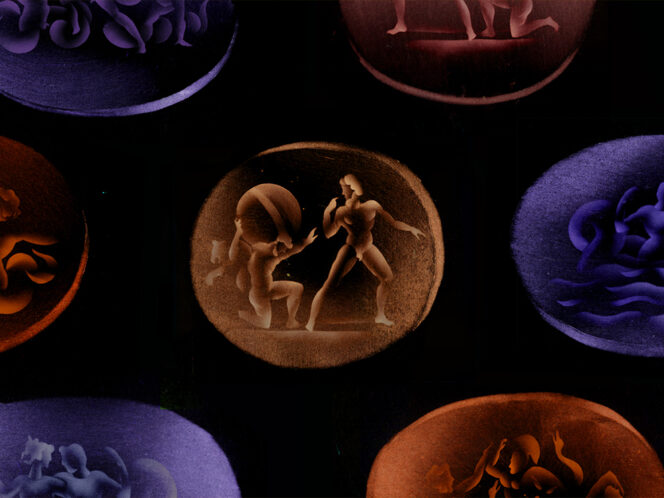

If we take into account the secrecy of Masonic ceremonies, it is not surprising that the ornaments used by Freemasons had to be equally puzzling. Although they looked like normal jewellery, their meaning was highly symbolic. Thus, the jewels embodied the arcana of Masonic knowledge, only comprehensible to initiated members.

When pocket watches were in fashion, fobs were a widely-used addition. Fobs were short watch chains that kept the chronometer from falling out of the owner’s pocket. The chain usually had a radial ending, used to attach other decorative objects. Thus wearers could present various symbolic pendants as discreet signs of membership in their chosen organization. However, the most intriguing objects of this sort were undoubtedly Masonic crosses.

These jewels are still produced today, but the most beautiful ones were made in the 19th century. At first glance, they seem to be simple golden balls decorated with four little clamps and a small circle to hang by. Due to an ingenious placing of the hinges, the ball opens into the shape of a cross once the clamps are loosened. Each of the six segments of the cross has the shape of a pyramid with a circular base. The base used to be golden or gilded, and its walls were made of blackened silver. Each pyramid facet is marked by an engraved symbol – with a total of 24 engravings.

The placement and selection of symbols are not the same on each jewel, and their meaning depicts its owner’s principles. The symbols should be read from left to right, then top to bottom. Owners usually choose the Eye of Providence (the Grand Architect of the Universe), the Sun (direct, intuitive knowledge) and the Moon (sensitivity and feeling), a rope, a knot and two tassels (fraternal unity), a skull and crossbones (death and resurrection into new life), a rough ashlar (noviciate), an acacia branch (immortality), a perfect ashlar (mastery), as well as the following tools: a compass (wisdom), a square (balance, honesty, zeal), a trowel (cooperation), a hammer (work and power), a level (moral law) or a chisel (caring for others).

If a cross was purchased, its owner would obtain a convenient narrative description of the engraved symbols prepared by the jewel’s maker. Other artefacts also existed – for instance, jewels that formed a five-point star after opening and represented membership in the Order of the Eastern Star, or cube-shaped pendants that symbolized the road to a master’s perfection.

Moving jewels

Another, more formal kind of Masonic ornamentation are the so-called moving jewels. These small, metal emblems, fastened to the sash of a Masonic official, symbolize his power and the authority of his rank. Their design and meaning depend on the rites they are used for. The ornaments are called ‘moving’ because they are passed on from one Freemason to another. They do not have to be very valuable. However, some pieces are made of gold and precious stones. Pinned to the masters’ sashes, the artefacts show their level of initiation.

Rings

These jewels are not a mandatory Masonic accessory. They usually have the form of a signet engraved with a chosen symbol. They serve to underscore their owner’s adherence to Masonic goals and values.

The square and compass

The symbol of the compass juxtaposed with the square is a basic attribute in Masonic iconography. Stonemasons once used these tools on a daily basis.

The square has transcendental meaning and relies on allegory. Just as the mason uses it to make sure his work is balanced and proportionate, the square reminds the Freemason to treat others in a just and equal way. The same goes for the compass, once used to trace arcs and circles on stone. In Masonic iconography, it serve to remind its wearer about the need to follow established moral principles.

The letter G and the Eye of Providence

Sometimes, the symbol of the square and compass is enhanced with the letter G. The history of its use is most probably related to Scottish rites. Its specific interpretations may vary, depending on the brotherhood.

Some say the letter G should be read as the third letter of the Hebrew alphabet – gimel – that reflects the symbolism of mercy. Others read it as the initial letter of the word ‘gnosis’, meaning ‘knowledge’. However, the most common interpretation of the letter G presents it as the crucial Masonic symbol of the Great Architect of the Universe, a depiction of spiritual and intellectual ideas, instead of a personified God. Furthermore, all these meanings are enriched by the letter’s relation to geometry, which mediaeval builders believed to be the source of all knowledge.

The idea of connecting God and geometry – that is, faith and science – is another reference to Masonic tradition. Freemasons see it as originating from the history of ancient masters who participated in the great Biblical projects. The architects, fascinated by the great possibilities offered by geometry, saw it as a gift from God. The symbol of the Eye of Providence has a very similar meaning – the eye represents God, whereas the triangle stands for the mathematical perfection of geometry (although some also see it as a reminder that human thoughts and actions are closely scrutinized).

The Masonic twin pillars

Another extremely important Masonic symbol are the twin pillars, Jachin and Boaz. According to biblical sources, they were made of bronze (or brass) and guarded the entrance to the first Temple of King Solomon in Jerusalem. The word ‘Jachin’, spelled יָכִין, may be translated as ‘He will establish’ or ‘God has made steadfast’, whereas ‘Boa’ – בֹּעַז – signifies ‘strong’ or ‘in him (lies) strength’. The Jachin pillar stood on the right side of the temple portico, while Boaz stood on the left. Each was 18 ells (8.2 metres) high, with a circumference of 12 ells (1.8 metres diameter). The capitals were lily-shaped, 5 ells high (2.4 metres), decorated with palm leaves and pomegranates.

In Masonic iconography, Jachin references the idea of ascension as well as the concept of activity, and traditionally represents the male element. Boaz depicts the concept of wisdom and the passive forces of nature, connoting femininity. Both pillars remind onlookers about the limitations of the created world and symbolize dualism as a necessary manifestation of Unity.

***

Exact explanations of specific symbols and rituals cannot be divulged, since Freemasons are obliged to keep them secret. Nowadays, however, when information flows globally, many secrets – once dutifully guarded – have become common knowledge among the educated public.

Translated from the Polish by Joanna Piechura