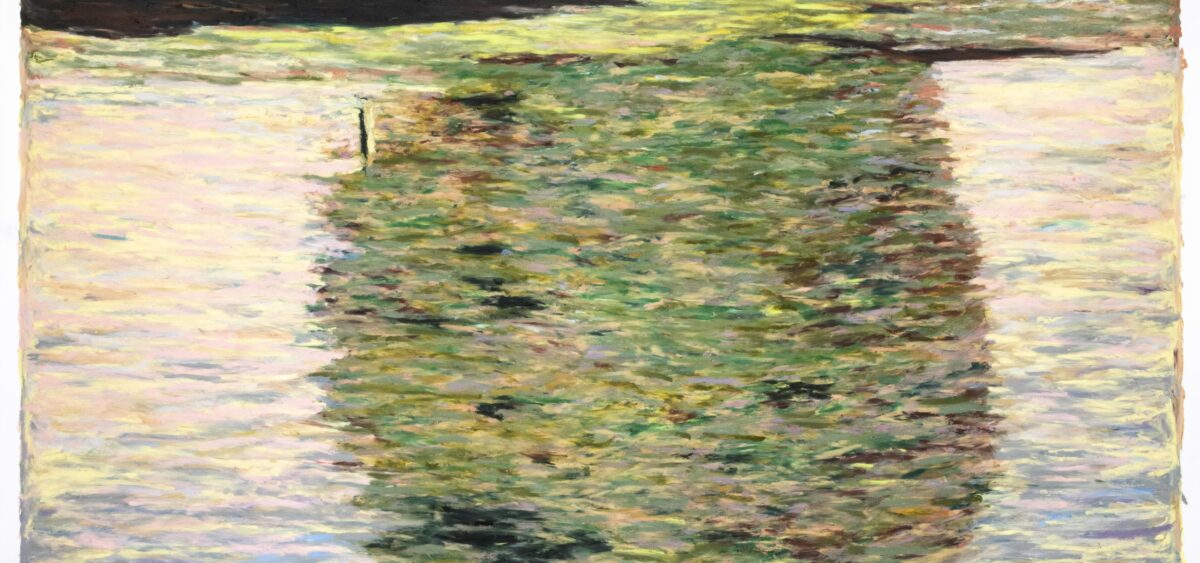

She is Ukraine’s most famous artist. She painted, drew, decorated ceramics, and embroidered. Her designs have graced postage stamps and coins, and she remains an inspiration to artists and textile designers today.

The world rediscovered Maria Prymachenko on February 27, 2022, when the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum (in Kyiv Oblast) had burned down following a Russian bombardment. Twenty-five of the artist’s works were inside, and local residents managed to rescue some of them.

Maria Prymachenko was born in 1909 into an artistically talented rural family in the village of Bolotnia. Her mother did embroidery, her father was a carpenter, and her grandmother painted Easter eggs. Just like another outstanding female artist—the surrealist painter Frida Kahlo—Prymachenko suffered from polio as a child, and she also wore long, hand-embroidered skirts to conceal her paralyzed leg.

She learned to draw, paint, and embroider at home. Even though she never acquired any artistic qualifications and had just four years of primary education, she became a professional embroiderer