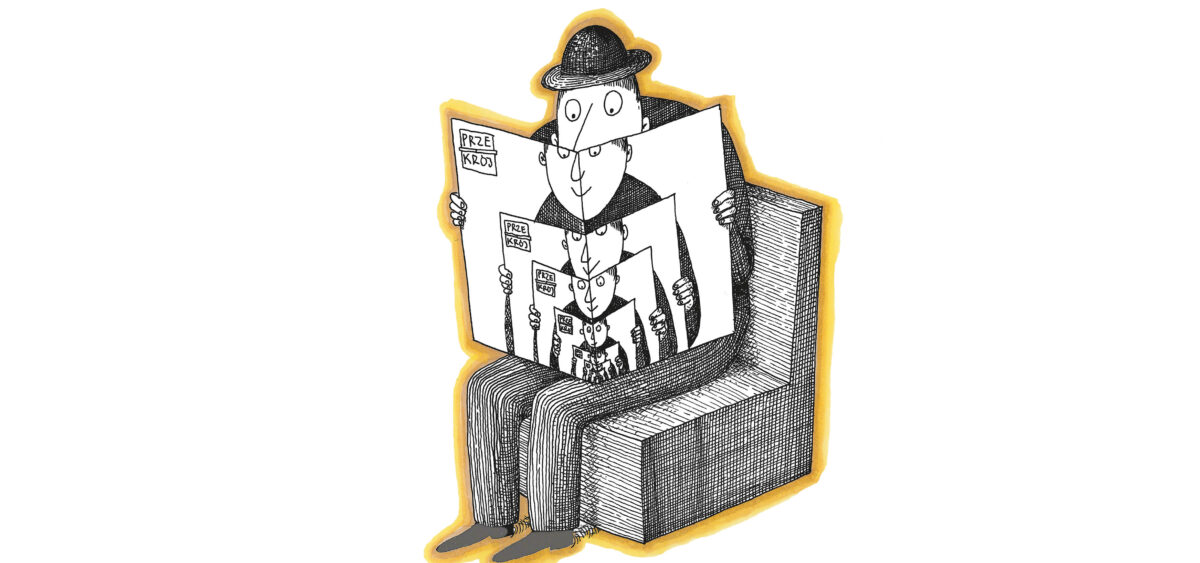

In the heavy, postwar atmosphere, a magazine was born, created from humor, absurdity, lightness, and color. Przekrój was a phenomenon. It was unlike anything else; set sideways to the course of the regime and operating in technical poverty. It was quite simply an impossibility. And yet, there it was, and everyone read it, from the back to the front.

The war was still on when the first issue came out in April 1945. An accident had helped its start. On a street in Łódź, Jerzy Borejsza, the head of a growing publishing empire called Czytelnik, bumped into Marian Eile. They knew each other from before the war when Eile had been secretary of the Wiadomości Literackie [Literary News]. Borejsza was looking for people to create a weekly illustrated supplement. Eile hopped into a little crop sprayer plane and flew as fast as he could down to Kraków, where priceless technical and intellectual materials were stored: printing presses that still worked and, living one above the other in the same tenement block, a group of writers and artists who had survived the wartime conflagration. Jerzy Putrament—who was meant to be the editor-in-chief—had the misfortune of being shot. During his recovery, he simply said to Eile: “Take my place.” So Eile took over—for the next twenty-four years and 1,277 weekly issues of Przekrój, without which, for many, life under socialism would have been unbearable. Years later, Agnieszka Osiecka wrote that Przekrój “was a lesson in laughter, tact, and sensitivity. Przekrój had created something which de facto didn’t exist: the illusive literary salon.” Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, who wrote for the weekly for many years and who was the author of the column Teatrzyk Zielona Gęś [Green Goose Theatre], put it more succinctly, inventing the notion of “Przekrój civilization.”

Przekrój’s Spark

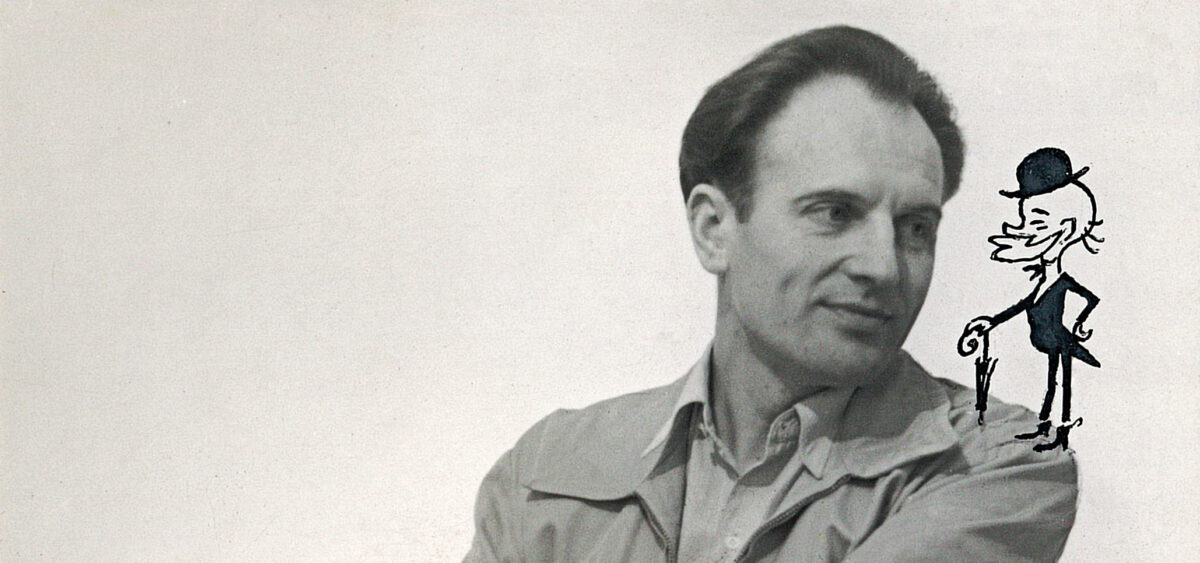

“Lightly; the magazine should have a light touch,” believed Eile, a permanently dissatisfied perfectionist. He was the ideal editor, who always spotted unnecessary words in a text and came up with the best titles. He was a skilled draughtsman and someone who liked to see everything through to the end. He was charismatic and very personable in private, but, at work, he was demanding and sometimes brusque. He knew how to inspire but also how to say no. To outstanding writers, who he would go on to employ for years, he would say grudgingly: “Well, stay for a trial period. One week…” He rarely gave praise. In his Paris days, he had soaked up refinement and style. He was popular with