My unwavering enthusiasm for Raymond Peynet and his collection of romantic, sensual illustrations titled The Lovers (Les Amoureux) dates back almost four decades.

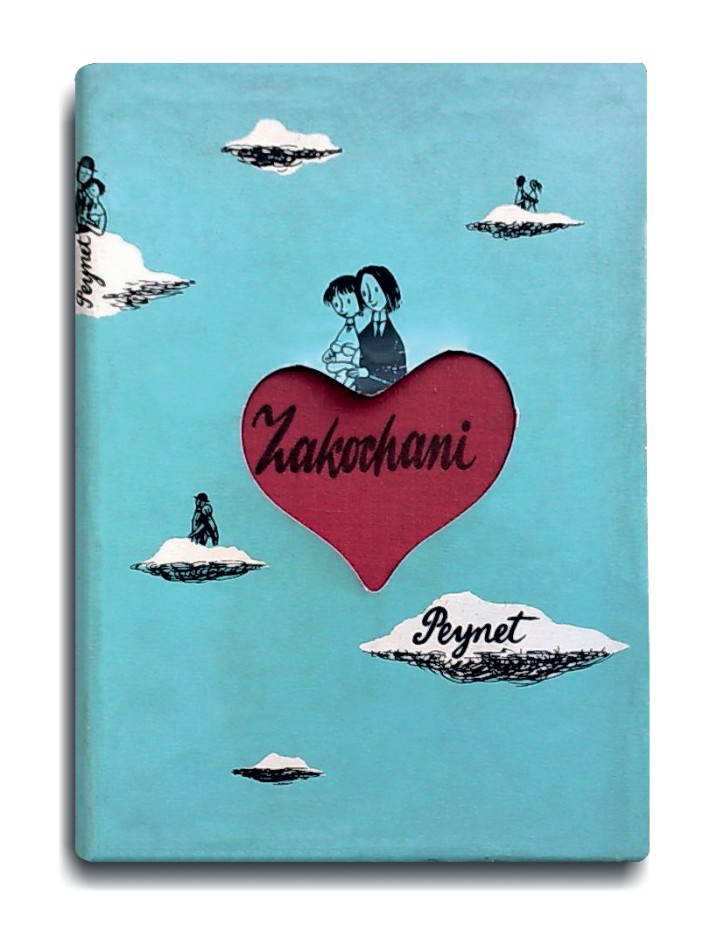

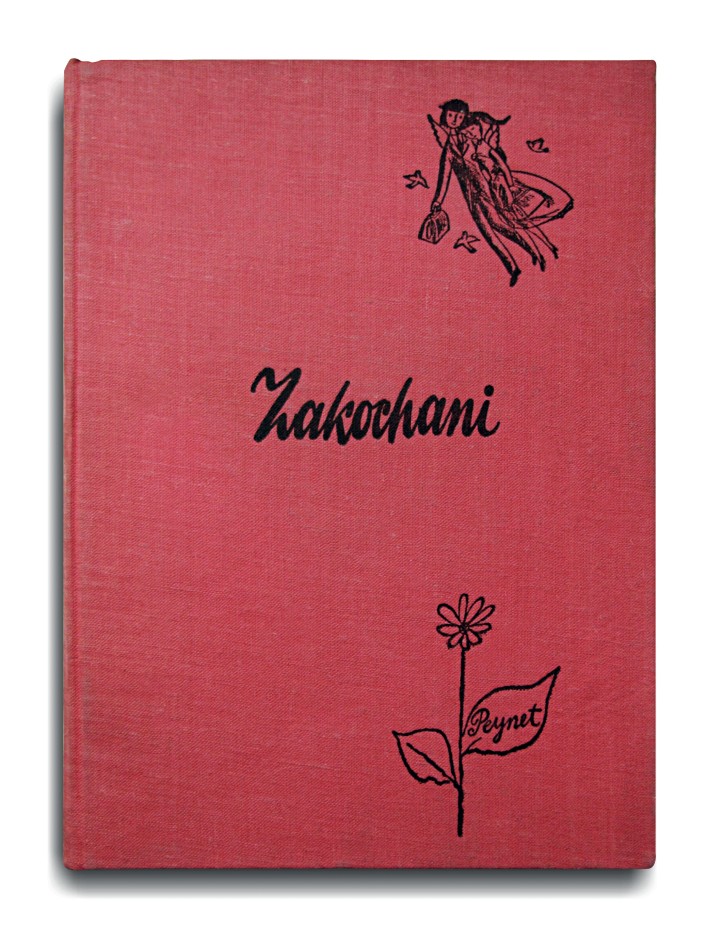

It began with a small claret-colored, cloth-bound tome published in 1958, which my parents received from some friends as their engagement gift. Years later, I discovered that originally it had also included a turquoise dust cover with a cut out, heart-shaped window in the center. I mention this because, as it happens, during my childhood this little book was a kind of window through which I could admire the world of romance, slightly tinged with a shade of erotica.

Even though I was still in short trousers, I was already fantasizing about passionate kisses. The rare glimpses of a derrière through