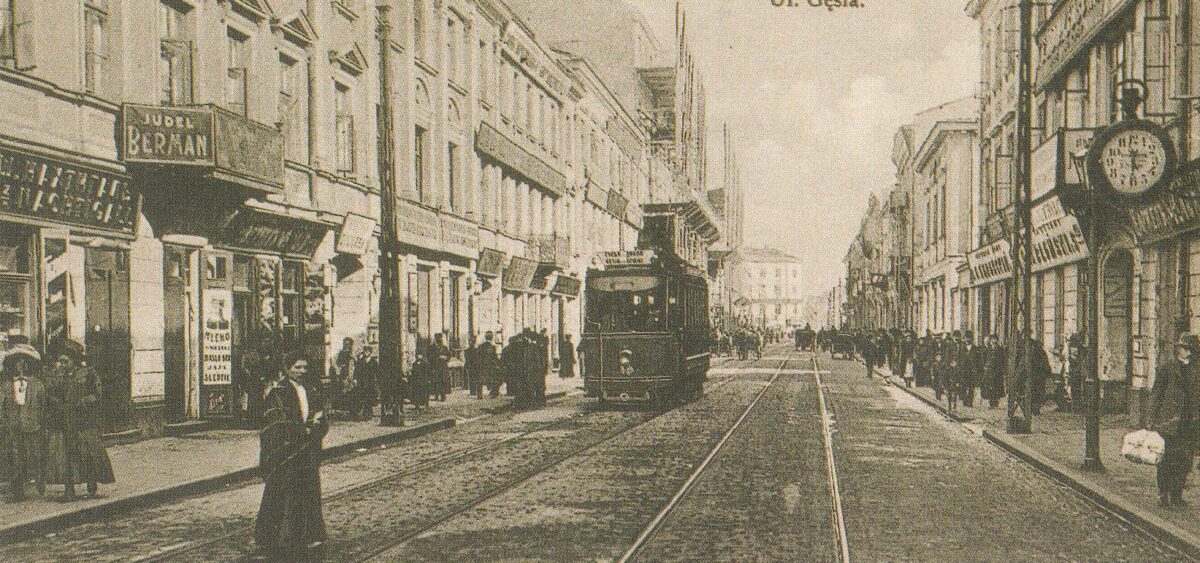

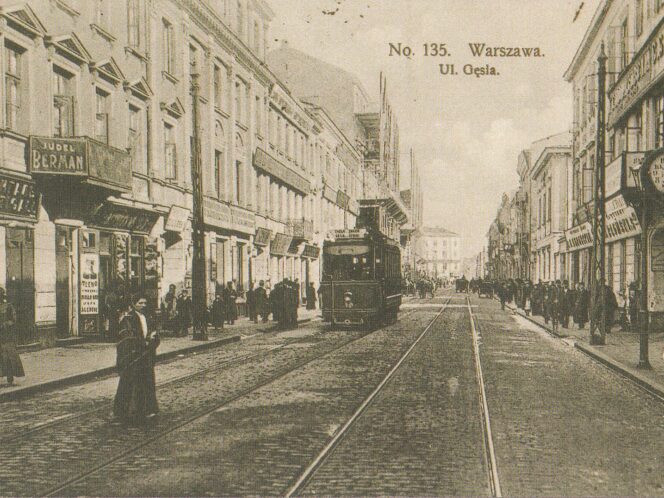

Post-war Warsaw, April. A group of people meets next to the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes to hear yet again the story of Izaak Feldwurm. Their narrator is the elderly Pan Abram, who knew Feldwurm from before the war and who even thinks that he once saw his legendary manuscript. But what was this legendary work all about and was it ever finished? Did it, as some claim, survive the war hidden in a tin receptacle under the rubble? Or was it rather destroyed by the author? And did Feldwurm himself survive? How else would he be pestering the living today – so many years later? Why would he not let himself be forgotten? Questions abound as the narrator of the story sets out in search of the manuscript and its legendary author…

He longed to be a writer. A great and famous writer like Yitskhok Leybush Peretz or Stefan Żeromski. When his office was closed, and so on Saturdays and feast-days, when he neither attended the promotional evenings of other authors nor visited the Hasidim, Izaak Feldwurm would write up the notes to his own book. He had been writing for years and was unable to finish it. According to friends, who referred to Feldwurm’s own confessions but had never seen the manuscript, it was a vast and vitally important novel about the city of Warsaw and its inhabitants. The action was to embrace several, if not fourteen generations. As to the main protagonists, Feldwurm had thought up over two dozen himself. They were merchants, clerks, staid middle-class townsfolk, rabbis and wonder-workers, but also representatives of Warsaw’s proletariat. Their stories were subtly interwoven; businesses passed from father to son; troubles with which grandmothers had wrestled affected granddaughters and great granddaughters. Some inherited servants, others poverty—as if in Feldwurm’s novelistic world no one was privileged to free themselves from their destiny, defined here once and for all, to some extent in harmony with the author’s fatalistic view of the deficiencies of earthly justice.