The point of departure for Sława Harasymowicz’s exhibition is a tragedy that took place in the closing days of World War II, in Neustadt Bay, near Lübeck. Prisoners evacuated from the Neuengamme concentration camp lost their lives in the bombardment of three German ships by the RAF; among those who perished was the artist’s great-uncle, Marian Górkiewicz.

The artist undertook years of research to learn the circumstances behind her relative’s death. However, the project seems endless. New clues pushed her towards different ways of interpreting the evidence and prompted her to ask more questions. This is essentially a utopian investigation, as it is based on objects that bear witness rather than people’s testimonies, on very scarce visual documentation contrasted with the overwhelming number of archival documents and reports in many different languages.

What happened on 3rd May 1945? Why did the Allies raid the German ships, despite the warnings about the prisoners on board (in a report partially declassified in the 1970s, it was described as a fatal error)? Why did the prisoners from Western European countries have the opportunity to leave the ships after the Red Cross intervention, while the other prisoners, from Poland and Russia, were forced to stay?

The research by Sława Harasymowicz is full of murky twists and turns, interlocking and astonishing stories involving both people and objects. The once luxurious Cap Arcona passenger liner had ‘sunk’ once before, as a stand-in for the Titanic in the Nazi anti-British propaganda film of 1943. Sequences from the film, in which we see the lush ship interiors decorated with artworks, are included in one of Harasymowicz’s works, H.N.5 515 (Film-Dream). The Thielbek was first torpedoed by the British in 1941 in Norway; then it was raised and repaired, only to be sunk in the depths of the Baltic Sea in Neustadt Bay four years later. Pulled from the sea after the disaster of 1945, the ship was noted to contain 800 tonnes of sludge. The silt was gradually removed and sifted through for over a month in search of human remains and preserved objects. The ship was cleaned and repaired, it would acquire new names and change hands; it remained in use till the mid-1970s.

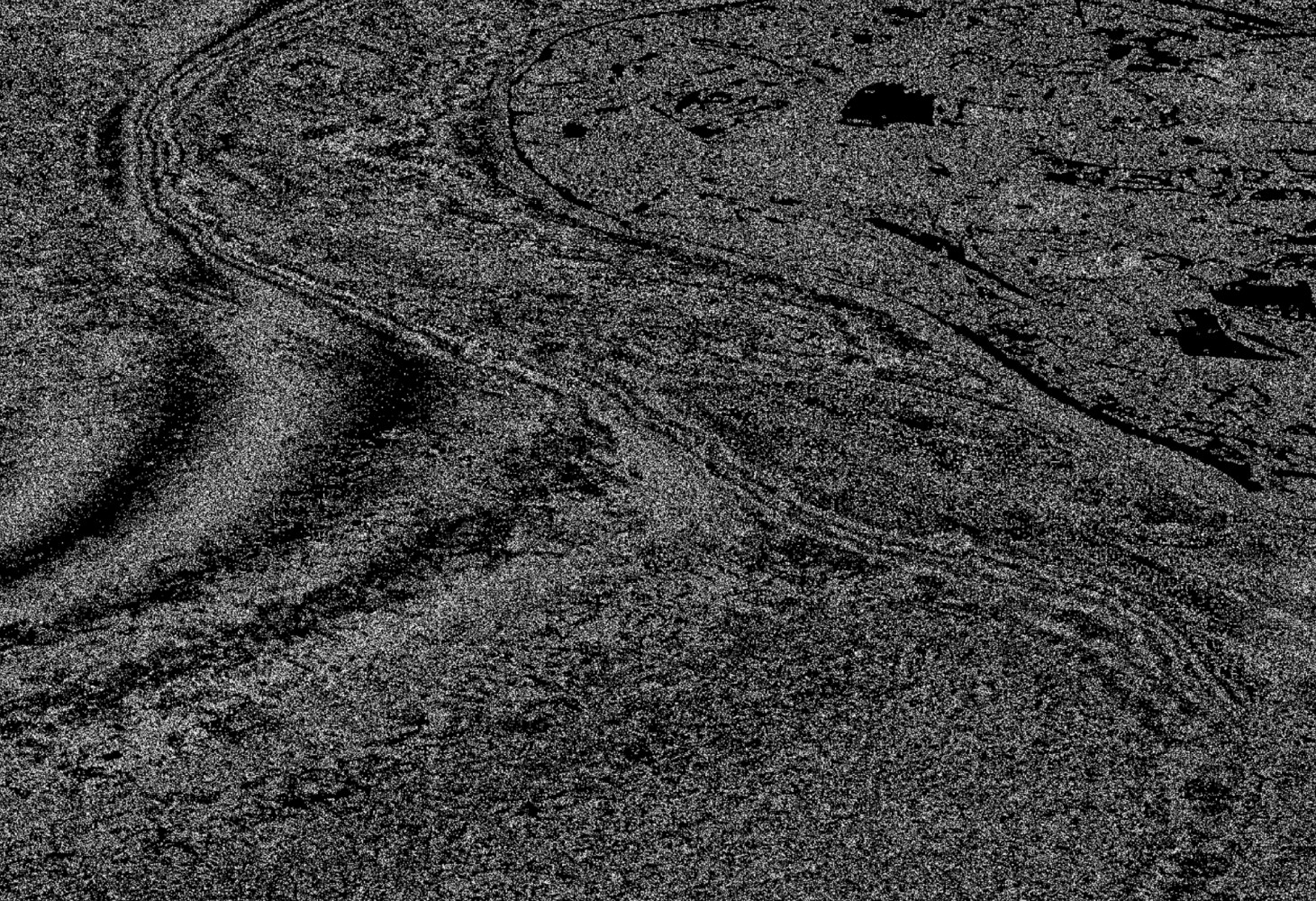

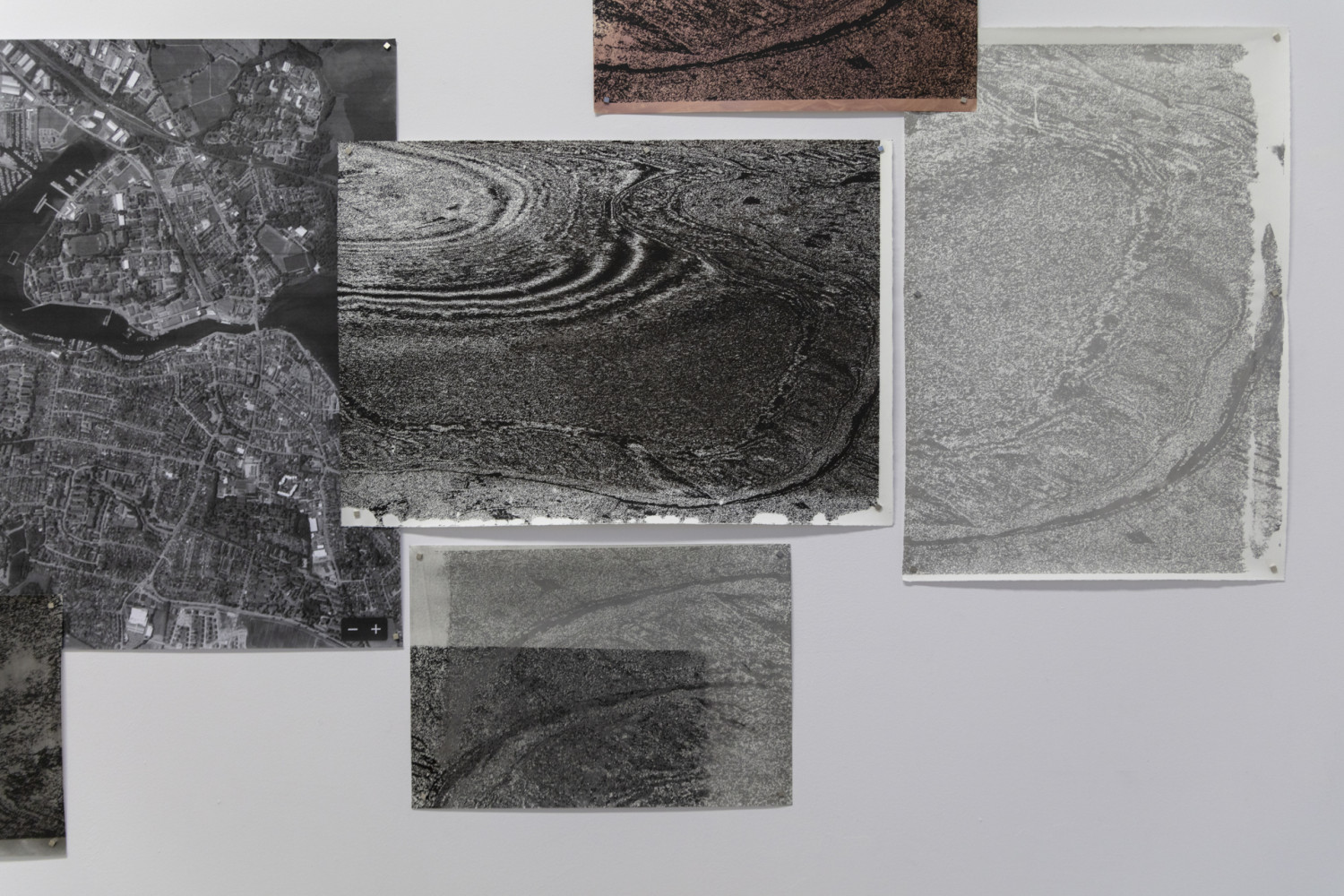

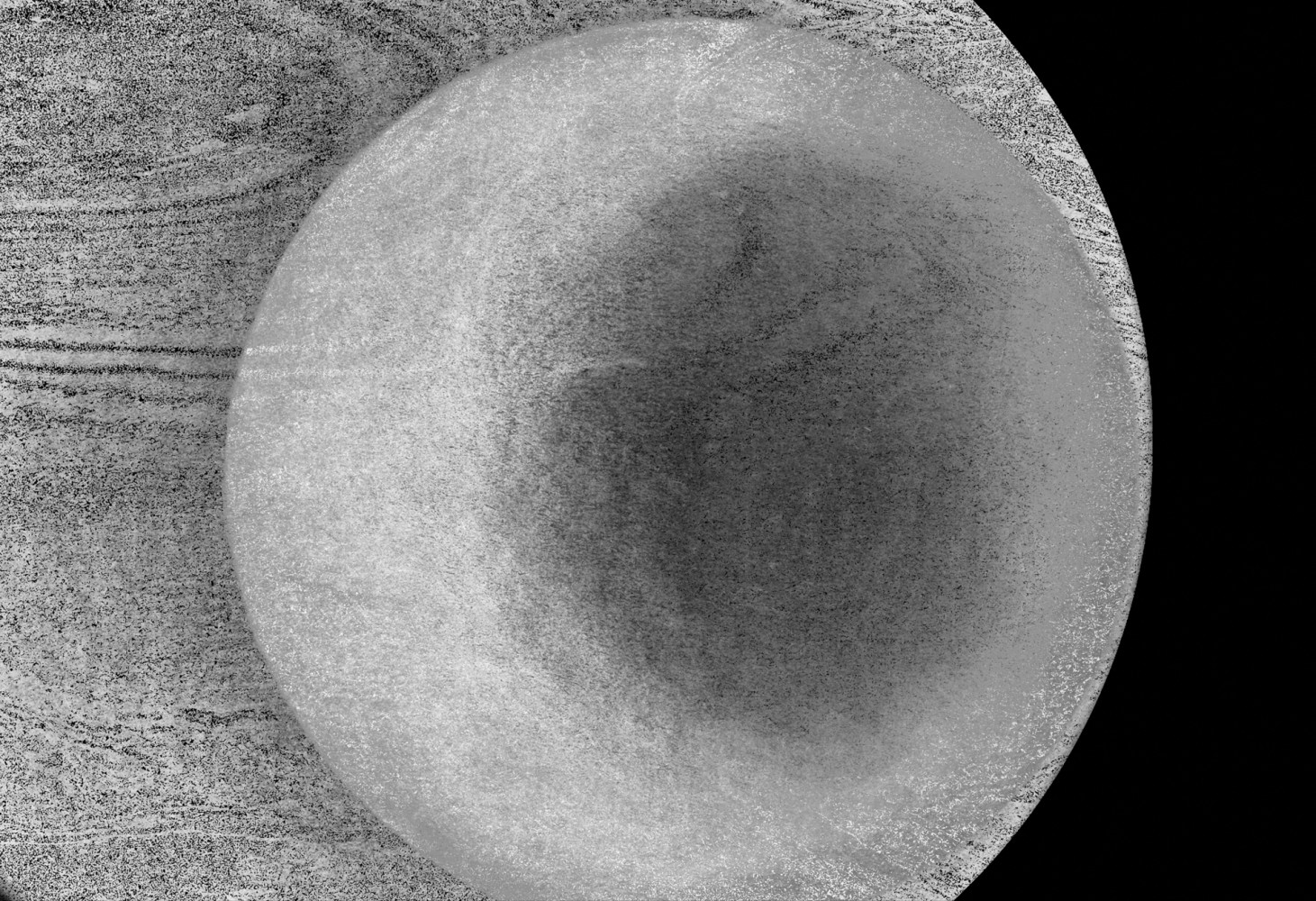

Among the possessions excavated from the sludge that covered Thielbek was a spoon that had belonged to Marian Górkiewicz. The artist addresses this part of the story and the shocking report on refloating the ship in her installation Silt. This work comprises hand-pulled screen prints, dense, thick and rough in texture, based on digital close-ups of a fragment of the bay obtained through Google Earth. The multiplied, fragmentary image forms a kind of reimagined map. However, this gesture of pulling in closer to the site of the tragedy does not offer any answers.

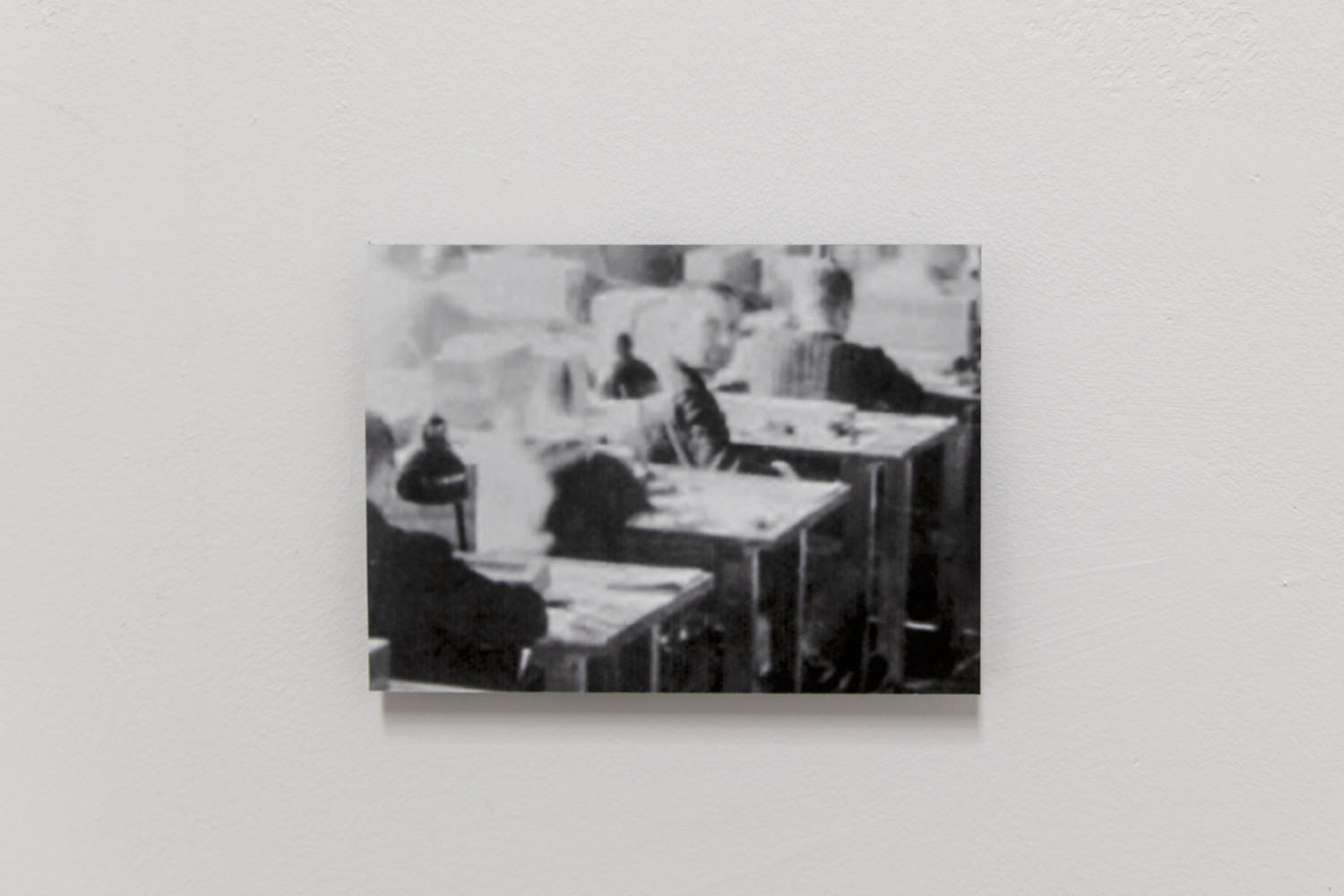

In an undercover photograph depicting the interiors of the workshop at the Neuengamme concentration camp (image dated 1941-44), prisoners can be seen using a magnifying glass and tweezers to construct miniature timer mechanisms for German anti-aircraft rockets. According to survivors’ testimonies, the work was painstaking and damaged people’s eyesight, causing severe headaches. In the exhibition, the close-up fragment of the photograph has been juxtaposed with a screen-printed work (Metals / Alloys), in which the artist adapted the archive’s list of alloys used in constructing the miniature timers. The artist also addressed the themes of visual acuity and impairment, straining one’s eyes, looking closely and gazing in her video Untitled (Perspective), a re-edit of British Ministry of Information archival footage from 1943-45. This work, which adheres to the video briefing form, presents the actions that precede air raids, such as viewing maps through optical devices, air surveys that enable the precise location of targets, and damage estimates – in the context of war, damage equals a mission’s success. The theme of vision is also discussed in the animated Untitled.

The exhibition opens with an image of burning ships. The photograph was taken from a distance, from the land, through an open window framing the image on the right. There is no information about this intriguing photograph from the collection of the Municipal Museum of Neustadt in Holstein. Who took it, and from what location? What does it show, and how can we get closer? This photographic image symbolically opens and at the same time closes Sława Harasymowicz’s exhibition, leaving the viewers without any clear answers.

Curators: Marta Przybyło, Anna Hornik

Sława Harasymowicz is a visual artist using drawing, photography and moving image along with more typical ‘graphic media’, such as screen-print or digital reproduction, in works exploring the relationships between text and meaning, word and context, art and language, (lack of) image and imagination. Her point of departure is often ‘archive’, as a strategy and a cognitive tool to pose questions around the validity of recollection, the ambiguity of reconstruction, political representation and autobiography.

Harasymowicz has recently exhibited at Archaeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw (2020), Crate Margate (2019) and Margate Town Museum in collaboration with Turner Contemporary (2018), BWA Gallery Tarnów (2018) and Bunkier Gallery, Kraków (2017-18). Alumna of the Royal College of Art London and the Jagiellonian University Kraków, she is currently undertaking a practice-based PhD in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London. She lives in East Kent on the North Sea Coast.