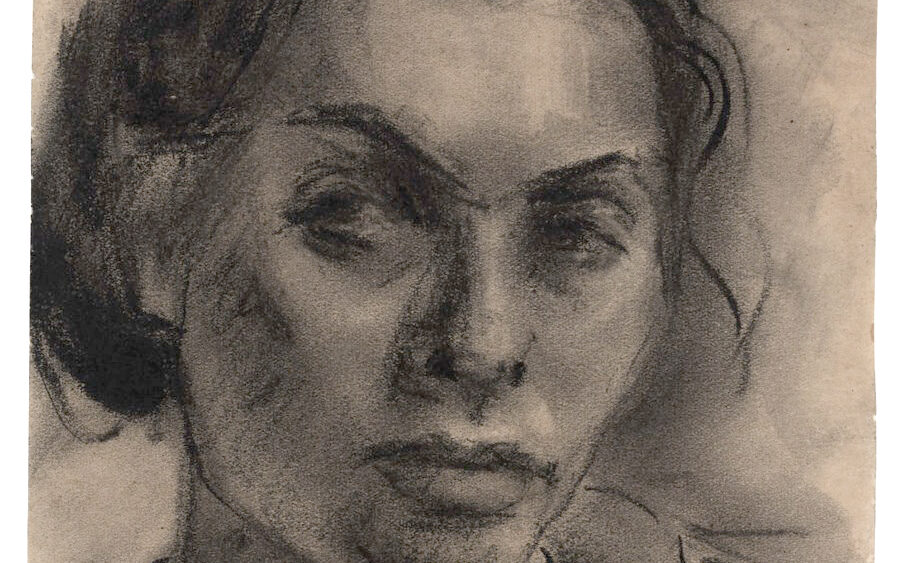

Painters, writers, musicians, actors. The residents of Poland’s Jewish Ghettoes—for whom living also meant creating—produced artistic works till the end. Sylwia Stano writes about those who didn’t let their love for beauty be taken away from them.

The first concert of the Jewish Symphonic Orchestra took place in Warsaw on November 25, 1940, nine days after the ghetto had been sealed. It was conducted by Marian Neuteich, composer and cellist, who set up the orchestra and became its artistic director. The programme featured, among others, Beethoven’s pieces, which were forbidden compositions.

In the ghetto, the symphonic repertoire was subject to many restrictions. First of all, the Germans only allowed the playing of ‘Jewish’ music. Therefore, it was permitted to play Bizet, Offenbach, Mendelssohn and Mahler, but not Chopin, Verdi, Mozart and Beethoven. Second, the musicians in the Ghetto didn’t have access to all the sheet music. Third, the make-up of the orchestra wasn’t complete, particularly when it came to wind instruments. For these reasons, numerous changes were made to classical pieces. Aleksander Rozensztejn, reviewer at Gazeta Żydowska (The Jewish Gazette), wrote in 1941: “The noble, romantic sound of the French horn was replaced with the somewhat bright and flat sound of the saxophone, but the intelligent and sensitive listener took this substitute as a necessity brought about by extraordinary conditions.”

Although the reviews didn’t mention it, Beethoven still belonged to the most often performed composers. Professor Marian Fuks cites Ludwik Hirszfeld, founder of the Polish School of Immunology, who wrote in his memoir The Story of One Life about the strange mood at concerts during which pieces forbidden by the occupiers were performed because “those malicious Jews loved Beethoven, and Brahms and Chopin, and they would rather risk imprisonment than give up on this timeless beauty. I even remember Beethoven’s 9th Symphony Ode to Joy being performed by the prisoners. . .