“It seemed strange to me that the human mind, through its knowledge, would not be capable of achieving that which had been granted by nature to creatures lower than we are,” wrote Tytus Liwiusz Burattini in the 17th-century Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as he enviously observed birds soaring in the air. He believed that thanks to the power of reason, humans would soon be able to fly as well.

Burattini was born in Italy (with the name Tito Livio) in 1617, where he received his education not only in the field of mathematical sciences, but also in architecture, languages and classic literature. This nobleman of modest means left for Egypt right after he had completed his studies, so that he could supplement his theoretical knowledge with experience gained in what was, at the time, a very exotic place. The young, multi-talented researcher worked hard at measuring pyramids, conducting archaeological excavations and drawing out maps of the country. Perhaps he had grown tired of the excessively hot climate, because at the beginning of the 1640s he left for Kraków.

He made a good choice. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, still wealthy and powerful, was an oasis of tolerance and civil liberties in a Europe ravaged by wars; a place where young, talented people from the West could find generous patrons and develop their careers. This was the path that Burattini wished to follow as well. He started his research work right away by, for example, designing a “scale so sensitive that a single hair disturbs its balance”, or by calculating the percentage composition of alloys based on Archimedes’ principle. Unfortunately, we don’t know what he specifically discovered and determined, because his dissertations on physics, notes from Egypt and other documents were stolen during a journey to Venice in 1645. As the ambitious Italian approached the age of 30, he had to start again from scratch.

Giving humans wings

Luckily, a year later, at the recommendation of Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga, Burattini ended up in Warsaw in the court of King Władysław IV Vasa. He impressed the King right away by presenting a treatise bearing a sensational title: “Flying is not impossible, contrary to what we have believed so far”.

Above all, he argued in his treatise that “we should not worry ourselves with considerations of the advantage that birds have over us, because while they have been privileged by nature, they have not been granted any material that would be lighter than air.”

“And while their feathers are very light,” he continued, “experience shows us that when dropped from high up, even the smallest of feathers will eventually fall, so if it weren’t for the rapid movement of their wings, birds would not only not be able to take flight, but would plummet to the ground with significant impact.” Having made that observation, Burattini started to design an ornithopter – a machine that would give people wings which they could move using their own muscles, such that the entire structure could fly in the air. His invention had the shape of a… dragon.

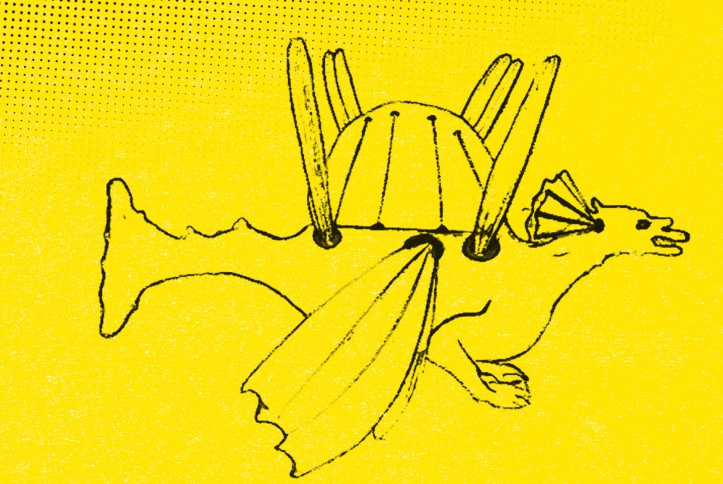

The dragon designed by Burattini had eight wings, powered by the movements of the pilot thanks to a system of levers and springs (which we regretfully know nothing about). The tail of the machine would work as a rudder, and the structure had to be made of wood and underwire, all of which was covered with material. What’s more, the hull of the dragon could be used as a boat if the machine had to land on water, while a parachute would provide additional security for the pilots. Therefore, if one of the wings were to break off, the designer explained, the machine “would not crash to the ground as a result, but would rather slowly fall down, such that the people inside would suffer only minor injury.” (Let’s add here that although a scant few inventors had already devised plans for parachutes, there was yet to be found a daredevil who would test the functioning of such a device in practice).

The dragon would ultimately fit two people inside, whereby it would be sufficient for only one of them to power the wings, while the other rested. The inventor also planned a space to store food and drink inside the vehicle – which would allow for journeys lasting days without landing – and also wanted to equip his ship with a compass, meaning that even night flights would not be an issue.

A cat flying in a dragon

We must remember here that the deliberations of the Italian inventor were quite original and proprietary then – this is because not many visionaries of the time believed that humans could take flight. Even the great Leonardo da Vinci, who had already studied the mechanical aspects of bird flight (and designed and tested a variety of models of flying ships in the 15th century), failed in this respect and never published the results of his investigations. Any subsequent trials to take flight had similarly ended in failure, and sometimes even in the death of the test pilot. Yet this did not discourage the creator of the flying dragon.

Information about the sensational invention quickly spread throughout the salons of Europe, while the accomplishments of the Italian, who was described as having “offered his mind to the Polish King” and having presented a “wonderful proposal of flying in the air”, were being keenly discussed in French, English and German courts.

Władysław IV himself also became personally interested in the project, and was probably witness to a remarkable demonstration. This is because in February 1648, a flying dragon took to the Warsaw skies. Sitting in the more-than-a-metre-long machine, in the role of test pilot, was a… cat. Burattini powered the mechanism that moved the wings using a rope, while one of the onlookers later described in a letter that if “the cat had possessed reason, which would have let it work the machine, it could have stayed in the air even longer.” Unfortunately, we do not find any information in historic sources regarding the fate of the courageous animal.

Burattini created another design for French scientists. To facilitate transport of the device, he prepared the model in parts for self-assembly, although he doubted that anyone would find a constructor in France able to assemble such a complicated machine. His concerns were quite well-founded, as chronicles do not mention anything about any similar dragons flying over Paris.

Nevertheless, it was Burattini’s ambition to create a device that would make airborne travel possible not only for cats, but for people as well. He believed that thanks to his invention, an airborne journey from Warsaw to Constantinople would take a mere 12 hours. Wladysław IV, no doubt looking forward to the potential military uses of such a device, committed to cover the cost of the construction of a full-size version of the machine. Feeling confident, the designer promised to finish work in eight months, and claimed that he would not accept any pay during that time. He did not want to receive his much-deserved reward until the dragon took to the sky with its crew.

Unfortunately, King Władysław IV died three months after the presentation of the flying model with the cat. His successor, Jan Kazimierz, had to grapple with a number of serious threats, such as the Khmelnytsky Uprising. Consequently, flights over Warsaw were not exactly the most important thing on his mind. Might the lack of interest from the new monarch merely have been a convenient excuse, allowing the Italian to honourably withdraw from further tests otherwise doomed to failure? Whatever the reason was, you’ll have a hard time finding any further mention of the flying dragon in historic sources.

Following Icarus

Burattini himself remained creatively engaged. He would continue to look into the sky, conducting astronomical observations through a telescope he designed himself, which resulted in his discovery of spots on Venus. He also made the lenses for Johannes Hevelius’s telescope. As we read in old letters, he was a clever mechanic too. It seems that he built a hydraulic machine powered by a windmill, which could supply even several thousands of barrels of water a day. He also publicized the Misura Universale, a scientific dissertation in which he developed the concept of a universal unit of measure, identical all over the world. In the meantime, he married a Polish girl, fathered a son, and in the times of the Deluge, fought by the side of Jan Kazimierz, organizing an infantry unit out of his own pocket. In recognition of his merit, he was granted a lease of the national mint. Although the issue of coins most likely did not give him much particular satisfaction, it did become his main source of income (simultaneously creating many enemies who would accuse him of fraud in the production of money).

Efforts to take flight by mimicking the movements of birds – attempts had been made ever since the times of Icarus, after all – finally became the dead-end of aviation, though many inventors would still try, even 250 years after Burattini. In the end, it wasn’t ornithopters that lifted humanity to the heavens, but rather balloons, gliders, sailplanes and airplanes. Regrettably, Burattini did not live to see those times. The Italian designer and inventor died in 1681 in Vilnius – he had apparently been living in such poverty then that he had no means for a proper burial. The final resting place of Tytus Liwiusz Burattini is unknown.

The knowledge we possess today suggests that there was no way that the flying dragon, powered exclusively by the muscles of the pilot, could ever have flown. What is interesting, though, is that in the works of Johann Joachim Becher, a 17th-century German doctor and chemist, we find a note about an eyewitness claiming to have seen how Burattini himself travelled in such a dragon over Warsaw… Did the Italian who “offered his mind to the Polish King”, indeed take flight? The most important thing is that he managed to bring people around to a very significant idea. Let’s recall the title of his dissertation: “Flying is not impossible, contrary to what we have believed so far”.