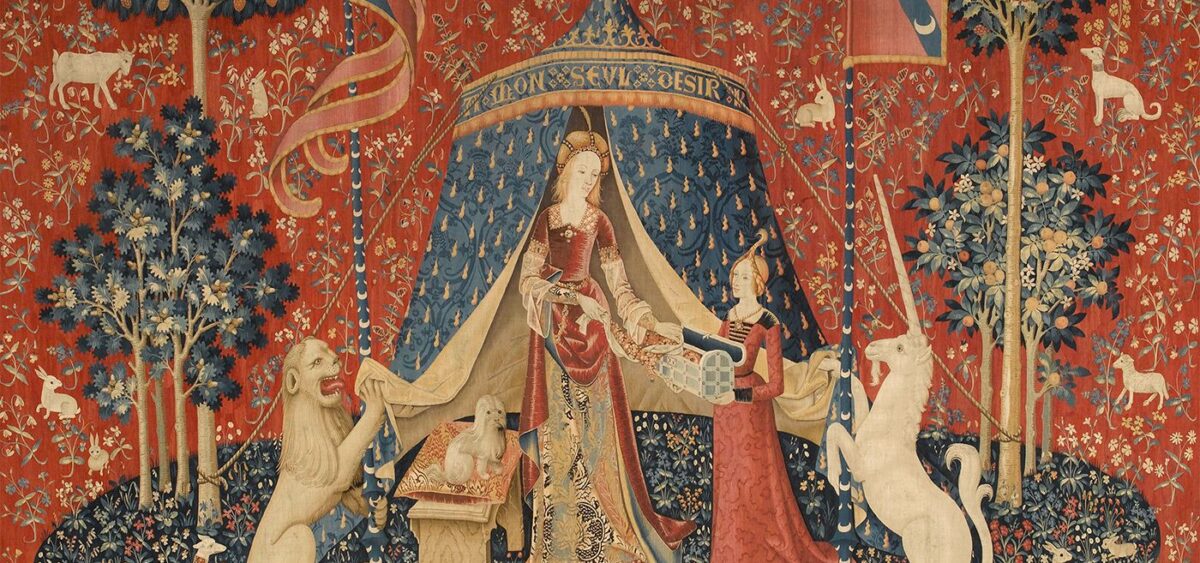

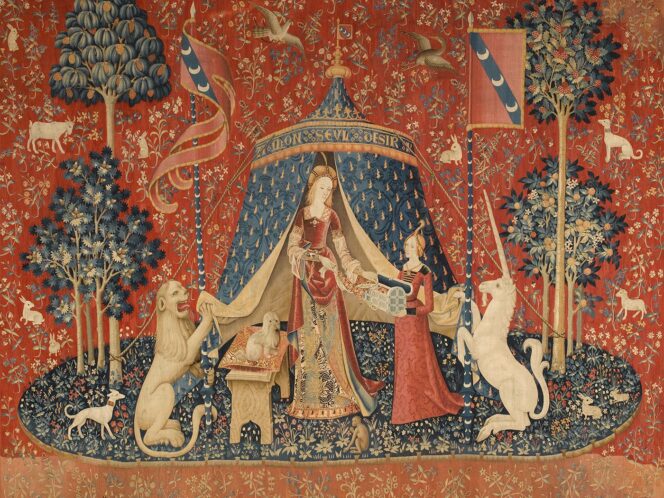

The best place to get lost would be among the tapestries of The Lady and the Unicorn at the Musée de Cluny in Paris. Agnieszka Drotkiewicz takes us on an extraordinary journey in the footsteps of George Sand (and others).

George Sand’s muddy shoes

The red is saturated and you can see the abundance of plants against it. Some of them are easy to identify, even for a moderately skilled naturalist: lily of the valley or daffodils here, wild strawberries there. Is this what the writer George Sand saw under her feet on a rainy day at Boussac Castle? It is hard to believe that Count de Carbonnière, one of the owners of the castle, would decide to place tapestries on the floor instead of carpets, but who knows?

There are some uncertainties and doubts surrounding the six tapestries depicting a lady and unicorn, exhibited today at the Musée de Cluny (or Musée National du Moyen Âge) in Paris. So perhaps this version is true: Sand, wiping her muddy shoes, looked carefully at the carpet on the floor. At that time, Boussac Castle was the seat of the sub-prefecture, and the writer came to settle official matters related to her house in nearby Nohant. The plant motif on the fabric reminded her of tapestries from the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. She forgot about the official business and asked whether there were any more tapestries. It turned out that yes, there were six – Sand’s notes mention eight tapestries; two of them were lost. Each one depicts a lady, her companion – both in gorgeous dresses