On 4th October 1951, Henrietta Lacks passes away from a very aggressive form of cancer.

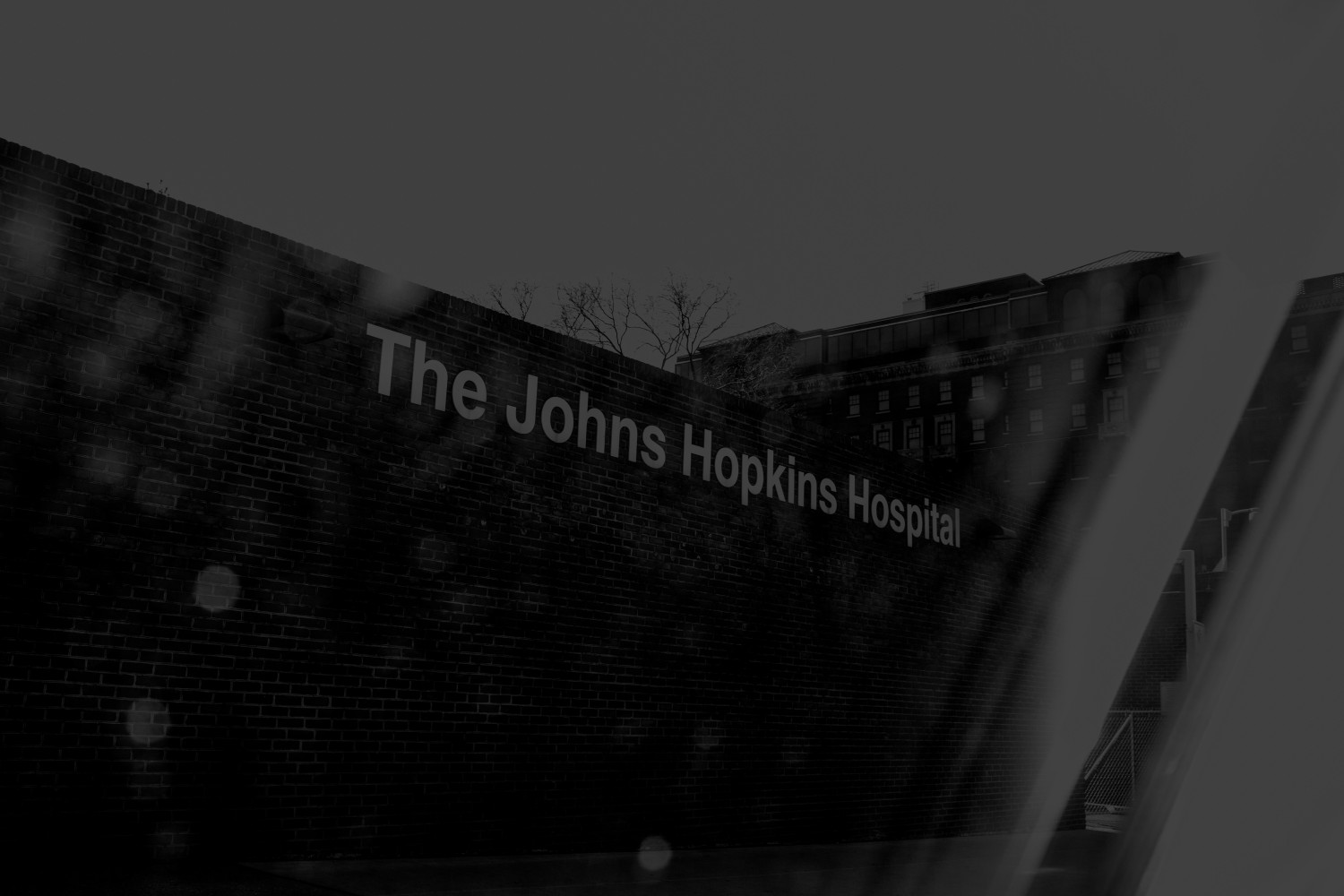

Then her last journey begins, from the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to the family cemetery in Virginia. Nobody knew at the time that another journey started for her, more precisely for her cells. A small sample of her tumour was taken without her knowledge by Dr George Gey. He baptized these cells HeLa (as in Henrietta Lacks), and was amazed to observe that they behaved in a way never seen before. Until then, human cell culture was impossible. Cells would decay quickly, but hers kept growing and multiplying, again and again, infinitely.

Henrietta could not know it, but she had become immortal.

This case is one of the most famous, and problematic, stories in modern medicine. Her family was an underprivileged African-American family, who had no idea that their mother/wife/cousin’s cellular material was used all over the world by researchers in thousands of experiments, vaccine developments, virus investigations, beauty product trials. Her cells were even exposed to nuclear bombs, and sent all the way up to space.

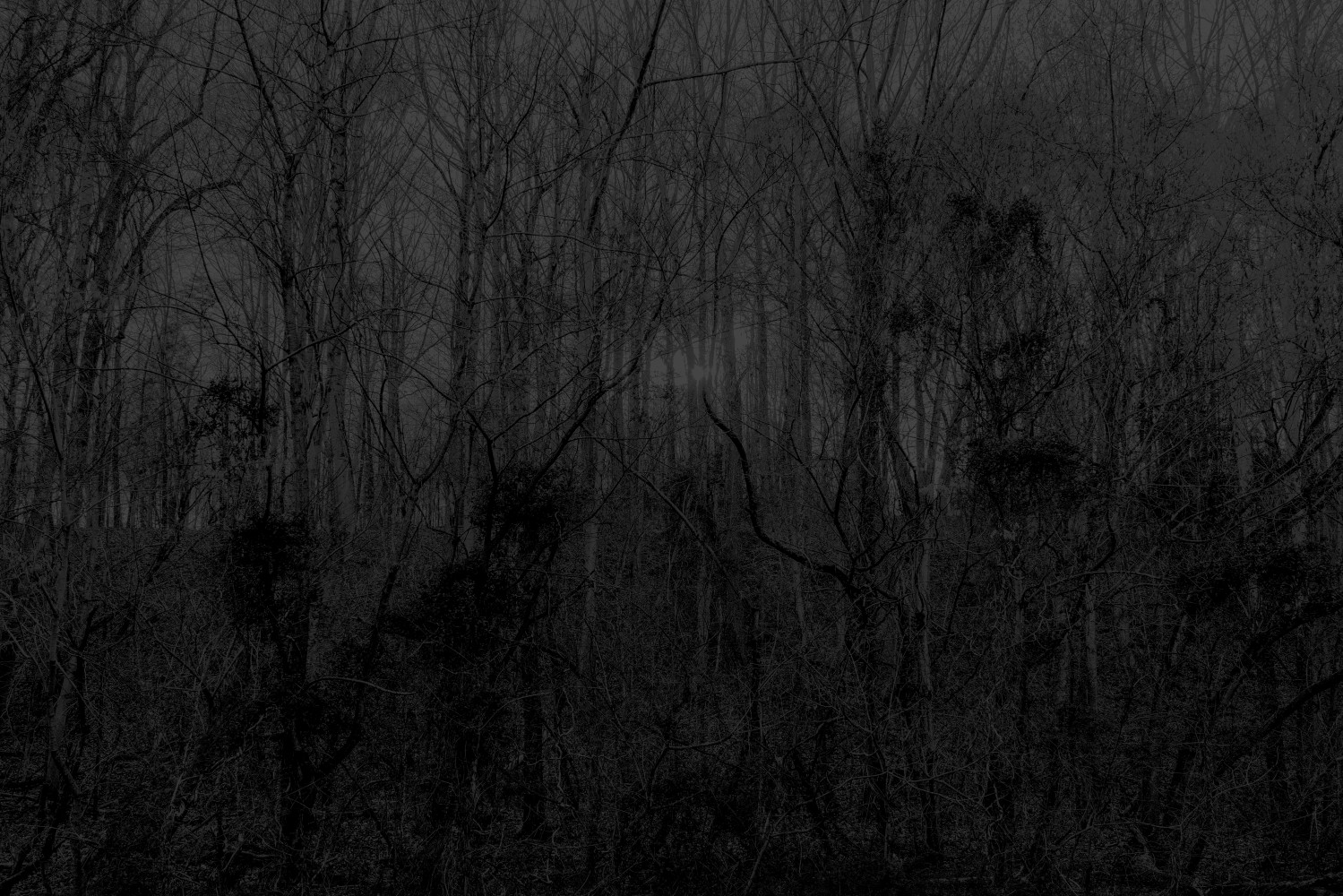

The installation of David Fathi’s work is designed as a road. The spectator follows a path. On one side are imposing pitch-black landscapes taken on Henrietta Lacks’ last road, punctuated by ghostly apparitions of HeLa cells. On the other side is text, data, in huge quantaties, describing in a direct manner the controversies of the story in five chapters: Segregation, Mutation, Contamination, Appropriation and Spacetime.

The Last Road of the Immortal Woman is where Henrietta Lacks is no longer alive, but not yet immortal. A liminal space separating mortality and immortality, the scientific and the emotional, the political and the personal, the metaphysical and the empirical, exploitation and recognition.

A funeral march for Henrietta Lacks, but a new beginning for her cells.