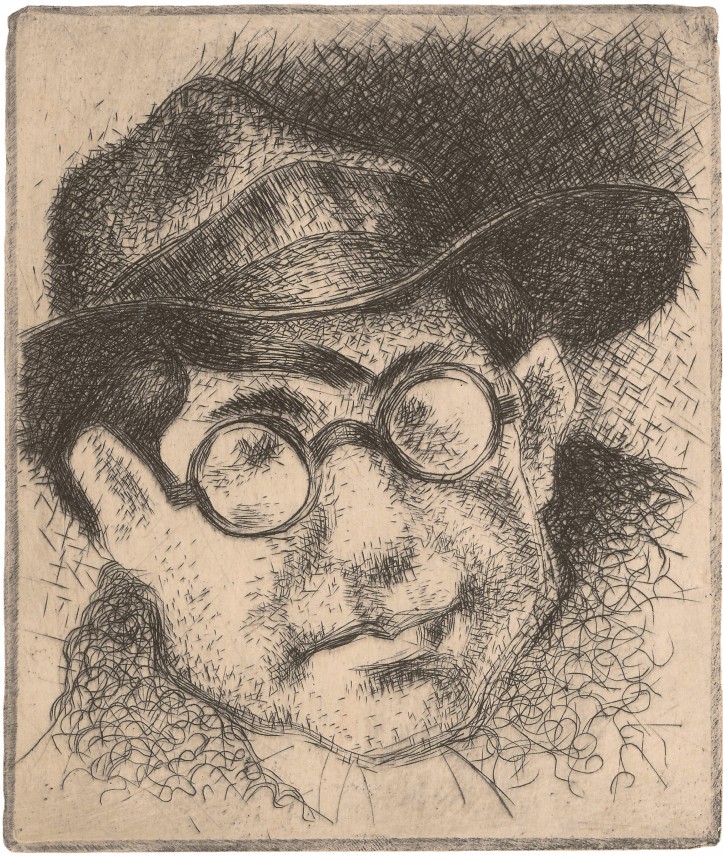

Leopold Lewicki’s talent was immediately spotted by the critics. They appreciated not only his innovative canvases, but also his grotesque prints, stylized to look as if created by a child. One of the critics even compared the artist to van Gogh.

Leopold Lewicki was born on 7th August 1906 in the village of Burdiakowce (modern-day Burdyakivtsi in Ukraine), not far from Czortków (Chortkiv) in the Tarnopol (Ternopil) Voivodeship, where his father Jan Lewicki was a blacksmith in the estate of Count Gołuchowski. Jan later worked as a metalworker in a railway depot, which was quite useful for Lelek – under which name the young Leopold was known – because, as a national railway worker’s family member, he was entitled to free train travel within the borders of the Polish state. Leopold’s mother – Olga, née Bluss – came from a Ukrainian family, and one of his grandmothers was Jewish. As a grown man, Leopold married Henia, daughter of Benzion Nadler from Czortków, and by doing this, he brought together the then three main blood strands of the historic Podolia region (in what is now western and central Ukraine).

In autumn of 1925, after graduating from the Juliusz Słowacki Gymnasium in Czortków, Lewicki began his studies in Kraków. At first, he enrolled at the Law Department of the Jagiellonian University, but in the end decided to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. He was a student of Władysław Jarocki and Józef Mehoffer. At the turn of 1930 and 1931, he went to Paris to continues his