The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw is holding an exhibition on traditional and contemporary anti-fascism in art.

It is September. We are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II. We are in a city that was razed to the ground by fascists and we have a crisis in democracy. Can you imagine a better time, location or circumstances in which to put on an art exhibition against war and fascism? The title of the exhibition sounds a little like moral blackmail. Never Again. Art against War and Fascism in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Can one possibly disagree with such art? Who supports war? Who is in favour of fascism? Even a decade ago, the answer to these questions would have been obvious to the point of being boring. However, we are living in interesting times in which the obvious of yesterday isn’t so obvious any more.

The contemporary definition, and even the moral evaluation of fascism, is becoming relative. Anti-fascism is a debatable notion. Even the slogan ‘Never Again War’ doesn’t sound as unambiguous as it once did, because history likes to repeat itself and mankind doesn’t learn from its mistakes. The exhibition itself becomes enigmatic. All very well for the exhibition, but at the same time, all the tougher for us.

***

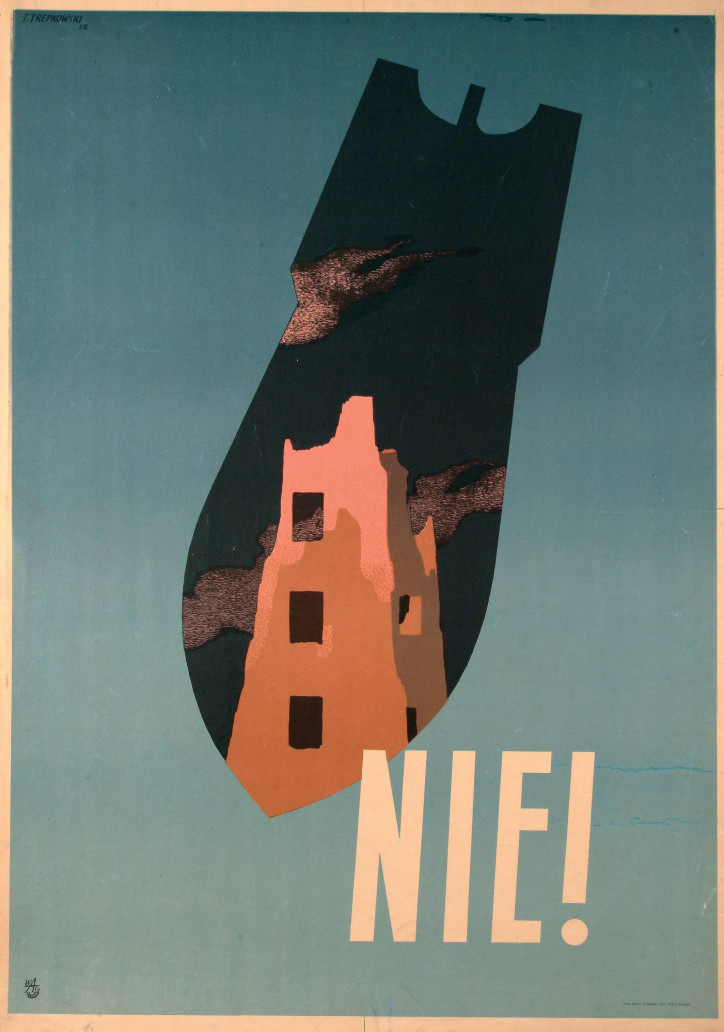

We enter the Museum of Modern Art (MSN) and we see, hanging at the back, one of the most important paintings of the 20th century: Guernica. It is not Picasso’s original, but we do have here the next best thing: Wojciech Fangor’s replica painted for the 1955 Festival of Youth and Students. Above Guernica hangs another iconic image, this time a local one: a Tadeusz Trepkowski poster from 1952. It shows a blue sky with a bomb flying across it. The outline of the bomb forms a window through which one sees the ruins of a burned town and the single word ‘Nie!’ (No!).

A very strong start that leads us perfectly into an anti-war and anti-fascist mindset, along with all the questions that provokes. What can art do about fascism? Where is the line between artistic creativity and propaganda? In extreme circumstances, can one resort to propaganda and still remain faithful to art? Should one? This exhibition addresses these questions across three different periods: the eve of the outbreak of World War II, the end of Stalinism, and the present day.

Human sandwich, or devour your Jews

We begin in the 1930s – in Poland, in Germany, and in Europe. Liberal democracy is in crisis (sound familiar?); fascism and its ideological clones are getting stronger. The forces of the People’s Front oppose them. Modern art, with a few exceptions, finds itself on the left side of the barricade in this conflict.

In the first part of the exhibition, we see many modernist paintings of demonstrations, protests, street fights. Fascists are fighting with socialists and communists; the forces of darkness struggle against the legions of light. Many of these works were created by Polish artists, particularly members of the pre-war Kraków Group. This is not a battle playing out symbolically; the streets really are running with blood. In this situation, for many artists the question about the boundary between art and propaganda becomes irrelevant. Among the artists from the 1930s on show at Never Again is John Heartfield, the German master of political photomontage. One of his works shows the process of making a human sandwich, bearing the caption: “Goebbels’ recipe for food shortages in Germany: What? No lard and butter to eat? Why don’t you just devour your Jews!”

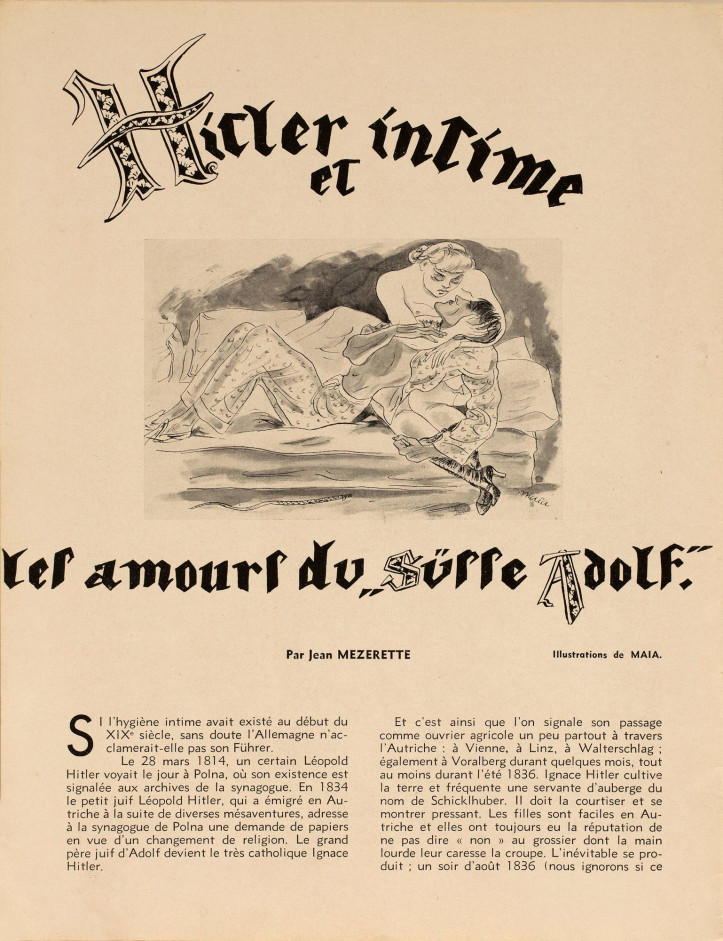

In Germany in 1933, artists like Heartfield or George Grosz – on display next to him – become cursed creators of ‘degenerative art’. This fate awaits others later on. The case of Maja Berezowska is instructive. In the exhibition we see a caricature of Hitler, which the artist published in a French satirical magazine while she was living in Paris in the 1930s. Miłostki słodkiego Adolfa [The Flings of Sweet Adolf] may be provocative, but is fundamentally harmless. Yet the subject was not amused by it, and did not forget it. During the occupation of Warsaw, the Gestapo tracked down and arrested the artist. A second series of her works on display at the exhibition come from the Pawiak prison and from Ravensbrück concentration camp, where Berezowska was sent in 1942 because of her art.

Picasso vacillates

Guernica is the most important – this is the central piece of the exhibition. In 1937, Pablo Picasso is fighting the Spanish Civil War with his paintbrush on the side of the Republicans; he paints a vision of the world shattered by the fascist bombs that Hitler’s Condor Legion has dropped on a Basque village. The painting is first shown at the Paris International Exposition, which, on the eve of war, becomes a symbolic battlefield between the forces of fascism and anti-fascism, fought through works of art, architecture and propaganda. Guernica, like a magnifying lens, focuses in on the engagement of art in the resistance against fascism. It also highlights the paradoxes of the anti-fascist movement. The greatest of these lay in the symbolic and organizational appropriation of the anti-fascist concept by Moscow, which skilfully cornered the European left of the 1930s. They had no alternative – the fight against fascism was synonymous with support for the USSR.

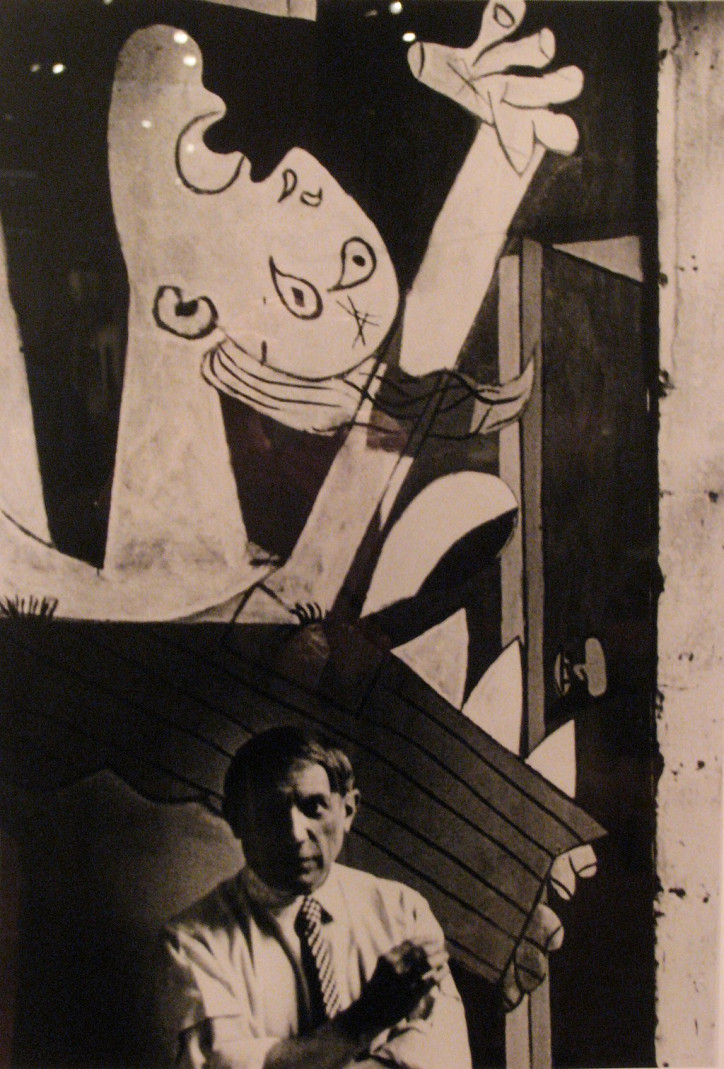

Totalitarianism or totalitarianism – Picasso found himself facing this choice too when painting Guernica. Among the most interesting exhibits on display in the MSN are the photographs that document the process of creating the legendary painting. They were made by Dora Maar, Picasso’s partner at the time, or rather the painter’s next victim. A retrospective of this unusual artist recently closed at the Pompidou Centre. A painter, photographer and surrealist, her works were absent from the art scene for decades, overshadowed by Picasso’s fame. In 1937, when Guernica was painted, the couple’s love affair had just begun and Maar photographed, step by step, the emergence of the painting from its enormous, empty canvas. These photographs are a chronicle of the birth of a masterpiece, but also a record of the ideological doubts of the artist. The early, sketched outlines of Guernica were thick with Communist International anti-fascist symbols – in the middle of the composition was the representation of a clenched fist. While painting the picture, Picasso was getting increasingly bad news from Spain about the role played by Soviet intelligence in the civil war and also about the Stalinists’ bloody dealings with Spanish anarchists. The anti-fascist emblems gradually disappear from the painting; there are none at all in the final picture. Guernica is still an artwork that targets fascism and, above all, is a protest against war, but in a symbolic sense Picasso maintains a distance from the anti-fascist movement that had been instrumentalized and manipulated by Stalin.

Meanwhile, the story of Guernica is only just beginning. Many political adventures still await it. The picture will become a universal source of anti-war inspiration, but will also fall victim to more than one manipulation. At the MSN, Picasso’s vision acts as a time machine that takes the viewer from the first chapter of the exhibition in the 1930s to the second. We remember, however, that the original masterpiece hangs peacefully in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, and the work we are looking at now in Warsaw is a copy painted by Wojciech Fangor.

It is 1955.

We defend peace down to the last bullet

Stalin is no longer alive, but Stalinism is still dragging on; Khrushchev will finish it off a year later with his ‘secret speech’. Historical fascism – the regimes of Hitler and Mussolini and their proteges and collaborators – has been vanquished. However, the fight with fascism is still going strong. Its official leader is still the Soviet Union. If, in the 1930s, Moscow was manipulating the anti-fascist movement, then we can say that after World War II it developed pretensions to owning the movement. In the vassal states of the Eastern Bloc, the authorities rework the protest movement into a propaganda machine. Anti-fascism in its Soviet incarnation has a new aesthetic form – before the war it was avant-garde, with leading modern artists engaged in the debate, but, in the eyes of the Stalinist culture bosses, modern art seems to be almost as degenerate as the creators of the political culture of the Third Reich. Simultaneously, the notion of fascism is watered down. The anti-fascist movement is now fighting above all with American imperialism, protesting against the war in Korea (which the Eastern Bloc is also indirectly engaged in) and condemning colonialism. Fascism becomes a synonym for capitalism and implicitly extends as far as the Western, anti-Soviet, liberal democracies. To paraphrase Göring, Stalin could easily have said: “In the post-war world, only I decide who is a fascist.”

Anti-fascism becomes indistinguishable from the call to fight for peace. This is fought on the fronts of the Cold War and is conducted through an arms race, with the militaristic, Soviet empire on the front line of battle. There is a grave risk that the final moments of the struggle for peace will cause the eruption of a new war, this time an atomic one.

Can one save an anti-fascist ideology and the authenticity of artistic pacifism that have been hijacked by communist propaganda to fuel to the Cold War conflict? The curators of Never Again are looking for answers to this question in Arsenal, the legendary exhibition that went down in history as the symbolic end of socialist realism in Poland. People forget that its official title was Against War, against Fascism. It took place in Warsaw in 1955 as part of the 5th International Festival of Youth and Students, organized under the patronage of the USSR. It was for this very festival that Wojciech Fangor painted his replica of Guernica, which was displayed in a public space in the city. It is hard to find a better backdrop for Picasso’s painting. Post-war Warsaw is itself one enormous Guernica. In the centre, on Stalin Square, gleams the new Palace of Culture and Science, but much of the land around still lies in ruins. The facades of destroyed buildings are hung with modernist decorations, monumental pacifist photo-montages, and the city becomes an art installation with an anti-war message. Delegations of progressive youth from 114 countries march through this scene, demonstrating their conviction that the only alternative to fascism and war is humanism – but only a socialist one.

In the press cuttings and archive photographs that document the festival at the MSN, we can see universal enthusiasm and ideological unity across the multinational diversity. Selected artworks from the Arsenal exhibition in 1955 are shown alongside the archival materials. Their authors are also demonstrating ‘against war and fascism’, but their tone is a long way from the upbeat atmosphere of the internationalist celebration being staged on the streets of Warsaw. The artworks from Arsenal are predominantly dark in palette and dramatic in content. The youth are not marching across them towards a glorious future. The artists’ focus is more on the victims of war than on its heroes. In their works, Izaak Celnikier and Marek Oberländer conjure up the ghost of the Holocaust, unrepresented in socialist realist art and never mentioned in the communist anti-fascist narrative. The anti-fascist art from Arsenal is closer to the drama of Guernica than the poetry of the propaganda posters. It is defined by humanism, but no longer a socialist one; rather a universal one, devoid of political adjectives.

The vaccine is losing its power

The history of the interplay between art and anti-fascism is fascinating, but would there be any sense in telling this story if no lesson could be drawn from it for today? The exhibition has numerous historical works and archive pieces, but all roads obviously lead to the present day. Is the darkening shadow that hangs over it cast by the return of fascism? Neo-fascism? Post-fascism? Are we again, as in the dark days of the 1930s, waiting for the voice of art to stand up to fascism, and do we need to re-think traditional anti-fascist culture? Can we learn something from it that will be useful in the contemporary struggle for peace? In the third part of the exhibition, therefore, we are teleported to the broadly-defined modern day. The end of history is long overdue and the history machine is rolling again. It is just hard to recognize the direction of travel. Towards a glorious future? Or maybe it is making a sharp U-turn and returning to a new 1930s, as the curators of Never Again suggest through their assembly of works by male and female artists who are, in the 21st century, once again encapsulating the spirit of anti-fascism in their works.

“The evaluation of 20th century totalitarianism, which seemed to be uncontroversial, has unexpectedly changed course, losing its cautionary power and its usefulness as an anti-war or anti-violence vaccine,” write the authors of the exhibition. “Is it possible that history is supposed to repeat itself in spite of the whole catalogue of knowledge we have accumulated about the consequences of ideological inflammation of conflicts triggering violent practices?”

What would we do without war?

“I congratulate Poland,” blurted out Donald Trump, congratulating us on the latest anniversary – the 80th already – of the outbreak of World War II. It is always nice to be congratulated, although this one was somewhat surprising. The September disaster, two bloody occupations, millions killed, Poland in ruins, first decimated by the Germans, then made a vassal of the USSR, not to mention the Holocaust… The President probably made a slip of the tongue. He didn’t mean to congratulate us, rather to express his condolences. Or maybe it was a slip, but not a normal one, more Freudian? I have the impression that the further we are from the outbreak of war, the more earnestly we congratulate ourselves that it broke out.

Travelling through 21st century Poland, from Warsaw Insurgents’ Square, I turn into Condemned Soldiers’ Street; I go along the Auschwitz Victims’ Embankment to the Victims of the Katyń Massacre Roundabout. As I walk past memorials to the Home Army and People’s Army, I pass squares named after various brigades, battalions, formations and forces.

What would we have done without World War II? What would we have called our squares and avenues? Instead of living on Defenders of Tobruk Street, we would probably be living on Pasqueflower or Little Pine Street. To whom would we have built memorials? We would have had to put them up for poets or, God forbid, scientists. Without World War II there would have been no heroic defence of Westerplatte, nor the phenomenon of the Underground State, nor even a trace of Polska Walcząca (Fighting Poland; an iconic anchor-shaped emblem symbolizing Polish resistance during World War II – ed. note); all these events, institutions and symbols that still so powerfully frame our imagination. Poland did not trigger World War II and yet we manage to paint our role in it – chiefly the role of victim – as the greatest achievement in the history of our national society. It is not surprising then that the Warsaw Uprising is the subject of particular pride. What would we have done without it?

I am frightened by the cult of World War II and of how its myths are placed at the very heart of our collective identity. For from mythology does there not flow a natural conclusion that there is nothing better for the nation than a good war that gives our lives collective glory, pathos and purpose?

Peace has reigned for too long, causing people to lose their sense of identity. They try to regain it by putting bumper stickers of Fighting Poland on their Passats and Golfs. I agree with the curators of the MSN, that the power of the pacifist vaccine on war psychosis is fading. I see it in the media, in street names and in the school curriculum my children are following, where World War II is presented not as a catastrophe, but as a unique opportunity to give one’s life, to spill blood and face huge losses. 80 years after September 1939, World War II in Poland is a popular, almost cult brand.

The concept of righteous war is being reinstated. Will it be accompanied by…

…a relapse into fascism?

The curators from the MSN are seeking answers in the works of contemporary male and female artists who are still striving for peace and democracy. However, their struggles resemble a fight waged in a museum where someone turned off the lights. You hear a footstep, someone or something is approaching, but from where? What? Who? Is unbridled capitalism the modern-day incarnation of fascism? Populism? Homophobia?

Or maybe racism? This is what Raymond Pettibon suggests in a series of torrid political drawings at the exhibition. So does The Polish Society of Friends of Maxwell Itoya, which exhibits documents from its citizens’ investigation into the police shooting of the unarmed Nigerian trader at the Stadion Dziesięcolecia open air market in Warsaw. Hito Steyerl, in a sparse but powerful video film, conjures up the morbid story of the persecution of the last Jewish inhabitant of Babenhausen, a small town in the German state of Hesse. The hero of this story, Tony Abraham Merin, put up with blackmail and threats for years. But when the neighbours burnt down his house, he finally gave in and emigrated. The shocking thing in this case is that, although these events would fit perfectly into the narrative of the 1920s, they in fact took place not so long ago, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in the liberal and united Federal Republic of Germany. Babenhausen became a ‘Jew free town’ only in 1993.

Martha Rosler, in her iconic collages House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, portrays how the middle class turns a blind eye to violence, tracking the fascist moment in American imperialism and in the neo-colonial adventures of the US, from Vietnam to Iraq. Does she hit the mark? Yes and no. Contemporary artists, driven by their instinct to defend democracy from fascist tendencies, are free of the political manipulation with which their predecessors from the 1930s and 1950s had to contend. Meanwhile, however, they seem to be struggling with a threat that appears to be ubiquitous but, paradoxically, at the same time difficult to pin down. Historical fascism metamorphosed into ‘eternal fascism’ whose defining characteristics Umberto Eco penetratingly presented in his famous lecture of 1995. The cult of tradition and heroism, irrationality, explaining the world through conspiracy theories, the fear of others, machismo, resistance to modernization, dreams of agency and power, the populist ‘elitism of the masses’, contempt for anyone weaker, and the replacement of discourse with newspeak – these are just some of the characteristics. Sound familiar? Of course they do. Many of these elements can be found in the political culture that is blooming around us, evolving across our television screens, in election campaigns and in party manifestos. At the MSN, however, we stop short of entering a space where we might actually engage with the current disputes. This is not an exhibition where we see clips from July 2019 in Białystok [where participants in the city’s first LGBT equality march were verbally and physically abused by a combination of football hooligans, the far-right, and others – ed. note], or supporters of the ONR [National Radical Camp, a far-right, ultranationalist organization active in the interwar period and revived more recently – ed. note] marching in formation through the streets of Warsaw, or the state-sponsored commemoration of the anniversary of the formation of the Brygada Świętokrzyska [a World War II underground military group, formed by the nationalist National Democracy movement and alleged to have collaborated with German Nazis – ed. note]. The closer we get to today, the more Never Again adopts a general tone. We stop at hints. In the spirit of the proverb “Two words are enough for a wise head”, anyone who wants to can draw concrete conclusions from the generalities. In this sense, the project is safe, even conservative.

However, even if the MSN had wanted to tread on dangerous ground – pointing the finger at those people and things that display symptoms of having been ‘bitten by fascism’ – it wouldn’t have been easy. The problem is that the components of Umberto’s ‘eternal fascism’ are strewn across various political and quasi-political discussions, from the nationalist right, through various colours of populism (including left-wing populism), to the Eurosceptic narrative, the alternative reality of fake news, or in seemingly apolitical phenomena, such as the anti-vaccine movement. It is questionable whether labelling the anti-vaxxers or homophobes or Brexiteers as fascists does anything to clarify the situation or assist in winning the argument. We live in an eclectic era, and contemporary ideologies are also eclectic; even the anti-democratic ones.

Do historical analogies, the main theme of the exhibition at the MSN, make any sense in this situation? Can the anti-fascist tradition in art still serve any practical purpose?

Wilhelm Sasnal exhibits paintings in which he reprises the icons of the anti-fascist-anti-war propaganda of the communist Polish People’s Republic. In one of them – a marvellous, grand canvas – the artist paints the monumental inscription ‘Never again’, which, in 1966, was erected at Westerplatte. The text is made from enormous flat letters with a gloomy, ominous forest wall darkening in the background. The form of this textual monument is compromised. It has bad connotations. In the times of First Secretaries Gomułka and Gierek, propaganda slogans about the leading role of the party were made from similar cut-out letters, monumental in scale, but arranged into empty words. On the other hand, one can’t fail to agree with the message of ‘Never again’; its origins in the People’s Republic do not invalidate it.

***

In Sasnal’s work, the question returns of what can be saved from the anti-fascist tradition and used today. Wolfgang Tillmans provides his own distinctive answer to this with a project that closes the exhibition and provides its punchline. The cult German photographer, who moves through the fringes of fashion, club culture and queer – a true poet of hedonism – has, for several years now, been putting increasing effort into fighting on the fronts of pro-democracy social campaigns. He has established a special foundation to do so. In 2016, he encouraged the British to remain in the EU, arguing against xenophobia and populism. Most recently, he was persuading the continent’s inhabitants to vote in the European Parliament elections. His engagement in these projects is more akin to modern marketing campaigns than the anti-fascist agitprop tradition that we see at the start of the exhibition. In Tillmans’ posters and billboards, he uses corporate and advertising language to defend democracy, tolerance and, last but not least, the European Union. “If Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini want to dissolve the European Union, what position do You hold?” asks the artist in one poster from his series entitled Protect the European Union against nationalism. Another poster from the same series strikes a tone that wouldn’t have embarrassed the organizers of the Festival of Youth and Students from 1955: “The European Union isn’t a faceless machine. The European Union represents 508 million people who live and work in peace.” So what is the message to take away from this anti-fascist experience? The good, old, bureaucratic European Union, which in its honesty seems almost boring and is unable to deliver dreams of heroic anti-fascist deeds? Maybe this is the nub of the matter? Nowadays populists are sexy and violence is spectacular, while anti-fascism has become a tedious, ineffective daily chore, like Tillmans’ campaigns. If so, alright then: let’s leave the exhibition and get down to work, as the German artist does. It is hard not to agree with him when he writes on one of his posters: “Democracy, peace and human rights have many enemies. Weakening the European Union strengthens them. Only as a united Europe can we oppose them. The European Union is not our enemy. It protects our rights.”

Never Again. Art against War and Fascism in the 20th and 21st Centuries.

Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw

Until 17th November 2019

Curators: Sebastian Cichocki, Joanna Mytkowska, Łukasz Ronduda, Aleksandra Urbańska

Translated by Annie Krasińska