In Europe, mandalas are usually associated with beautiful paintings in the shape of a circle, but in the East they have a deeper meaning—they are both a form and tool of meditation, as well as a symbolic reflection of the perfect order of the universe.

Carl Gustav Jung noticed their therapeutic dimension and recommended that his patients create mandalas. Today, they are increasingly used in art therapy as a method of restoring life balance.

Agnieszka Rostkowska: Since when have people created mandalas?

Luiza Poreda: I believe forever. One of the cave paintings from the Paleolithic era can be considered as the first mandala; next to depictions of animals and other elements of nature, archeologists discovered a drawing of a circle with a dot in the middle. Presumably, a human tried to grasp the reality around them in this way: they presented reality as a circle and themself as a point in the middle. We may wonder if this was not the first manifestation of the self-consciousness of a human who saw themself as part of the world. They chose the circle, most likely referring to the spherical form of the sun, which was worshiped by people as a deity. Circle and oval patterns can be found in many prehistoric paintings in Africa, Europe, and North America. References to the circle as the most perfect shape occur in subsequent epochs—from ancient and medieval philosophy to Leonardo da Vinci, who presented his Vitruvian man in a circle—and in various cultures, such as the Indigenous peoples of South America, the Celts, and the Slavs.

The term “mandala” comes from Sanskrit, in which it means a “circle.” Has the mandala always been a drawing or painting in the shape of a circle?

No, it can be a low relief, a sculpture, or an element of architecture, such as the Gothic church rosettes. In a broader sense, it can also be an experience. For example, dancing in a circle, as in the Israeli hora chadera or the whirling dervishes, which also has a mystical dimension. The mandala is also a meditation tool.

Just like yantras—geometric figures of special significance in Hinduism and Tantrism?

Yantras are symbols of the so-called sacred geometry, which is a collection of ancient patterns that in Eastern religions are a representation of the divine energy of the universe and cosmic order. One of the most important is Śri Yantra, formed by nine interconnected triangles: four pointing upwards, symbolizing the god Shiva and masculine energy, and five pointing downwards, representing the goddess Shakti and feminine energy. Overlapping with one another, they form a total of forty-three triangles—a network reflecting the entire universe, with the bindu point in the middle as the center of the cosmos. Śri Yantra is surrounded by two circles in which lotus petals, the most characteristic element of Hindu mandalas, are inscribed. The whole is framed with a square symbolizing the temple with its four gates overlooking the main directions of the world.

Yantras are used for meditation. You can look at them, which helps to calm the mind and builds mental balance, or draw them, and this requires a lot of precision and develops concentration and cognitive skills.

The element of a circle and square is always present in Buddhist mandalas.

In Buddhism, especially the Tibetan variety, the circle symbolizes the universe and infinity, and the square symbolizes earthly life. Therefore, in these mandalas, the square is usually inscribed in a circle, which represents the order of the world. Nothing in Buddhist mandalas is accidental: the colors, elements, and their arrangement are supposed to reflect reality and the laws governing it. In the center, which is both the beginning and the end of the whole system, most often there is a stupa—a sacred building, a material representation of enlightenment—shown on a flat plane, from a bird’s eye view, so at first glance it is difficult to recognize. These mandalas also contain figurative elements, such as figures of the Buddha or lotus flowers symbolizing rebirth and purity, among others.

Buddhist mandalas can be woven, painted, but also made of sand—the last of which is destroyed almost immediately after creating it. Why?

This is a special type of mandala made of finely-ground rice flour or sand, dyed in distinctive colors. Nowadays practices differ, but according to tradition, only monks deal with their construction. They create such a mandala for many days, after which they destroy it. Its creation is a kind of prayer, and its destruction—a practice of detachment which has a great transformative significance in spiritual development. It is also a form of meditation which shows that from a cosmic perspective, our existence lasts only a moment. We are like those colorful grains that can be blown away in a split second.

What can the act of creating mandalas give to a Westerner who is not a Buddhist and doesn’t even meditate?

In the West, we associate meditation with the East because it came to us from there. But people have meditated everywhere, regardless of religion or cultural background. They would sit under a tree to breathe, or by the seashore to watch the waves—that’s meditation too. And its active forms can be dancing, singing, or just drawing mandalas. Mandalas allow you to cut off from excessive stimuli and thoughts, to be in the “here and now.” They can help you make a deeper connection with yourself—your emotions, and even what’s hidden in the unconscious.

Carl Gustav Jung was fascinated by this aspect of reconnecting consciousness with the unconscious. He saw a psychotherapeutic tool in mandalas.

Jung was interested in Eastern culture, and creating mandalas became for him a method of getting out of a mental crisis. As a military doctor during the First World War, he created mandalas to break away from the reality of war. Apparently, for many months he painted a new one every day, referring to the moment and the emotions he felt. In this way, he personally experienced their therapeutic effects. Later, he began to use mandala formation in psychotherapy, working with his patients. He encouraged them to draw with emotions, to try to express them by means of a drawing enclosed in a circle created spontaneously, without planned shapes or colors. A detailed case study of one of his patients, along with descriptions of the mandalas she had painted, was included in his book Mandala Symbolism.

This publication was received rather coldly. Jung was accused of mixing order with nonchalant freedom; moving from neuroanatomy—for example, the relationship of the mandala with the self, which according to him was located in the brainstem—to Eastern religious systems.

Mandala Symbolism is the least known and least respected book in his oeuvre. Referring to the functions that mandalas play in Eastern cultures, Jung introduced them into his work with patients, but psychoanalysts of the time decided that this method was imprecise, and the fascination with Eastern cultures and religions, which Jung manifested at the end of his life, irritated them. In the book, Jung described his observations made during therapeutic work. At certain stages of psychotherapy, patients began to draw round shapes spontaneously. According to Jung, this choice reflected the desire of a person in a mental crisis to integrate difficult experiences. In people with schizophrenia who were going through a psychotic episode, he referred to this as protection against personality breakdown. Jung decided that drawing mandalas is a manifestation of the psyche’s desire for healing—both in adults and in children, who, for example, might have experienced the divorce of their parents. We all experience various difficulties and must face many daily challenges, so creating mandalas can be helpful for anyone and at every stage of life. I created my first mandala when I was lying at home suffering from tonsillitis, which also affected me mentally. I drew the mandala for hours and it brought me incredible relief.

So you gave the canvas all the difficult emotions, as is done in art therapy in Vedic Art, among others?

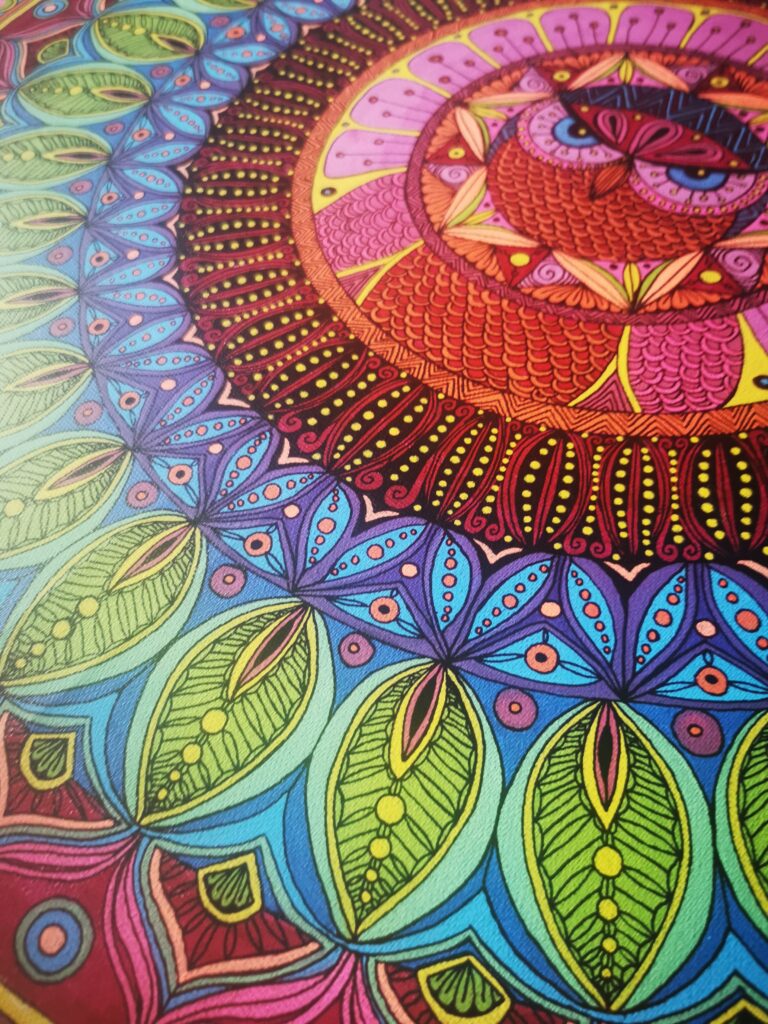

The aim of Vedic Art is to “pour” emotions out of oneself—often with a broad, expressive gesture—using any abstract forms or simply spontaneously applied patches of color. However, in the mandala, we carefully create complex patterns, often practicing deep concentration, precision—in silence and for many hours. My way of creating mandalas is an attempt to combine the Jungian method with the surrealist automatic notation. The surrealists mostly wrote texts in this way: sitting down in front of a blank page, they tried not to think about the words coming from their pen. They wanted to break away from the ordering mind and enter a state in which the hand is guided more by feeling, emotions, a kind of intuition. In this way, they tried to reach a place at the junction of dreaming and wakefulness: what is real and what is unreal. It was there that the secrets of the unconscious were to be hidden. I believe that similar work with the mandala allows us to reach the hidden contents of our mind.

In his book, Jung gave interpretations of mandalas created by his patients; he even included tables with explanations of the symbols and archetypes. At the same time, he pointed out that the final interpretation can only belong to the author. Are we really the only ones who can interpret our mandala accurately?

I believe so, and this belief is confirmed by every class I conduct. I have been teaching others how to paint mandalas for several years. I always start with the technical basics, because first you have to use a ruler to determine the center point, draw circles with a compass, and divide them into equal parts with a protractor. Only after constructing such a geometric skeleton can we start creating intuitively. I remember when a participant came to one of the workshops with her leg in a splint. She had already had knee surgery and had a long rehabilitation ahead of her—all because of a car accident. She didn’t know what she wanted to paint. I asked her to just start creating, instead of thinking about the concept. She painted a completely abstract mandala, patterns concentrically distributed in the circles. She looked at them for a long time and then said: “Luiza, I don’t believe what I painted! Look, these triangles are pieces of the broken car windows—the glass that stuck in my leg!” And she explained it, element by element, to me—and, really, to herself. Each of them was related to her accident. Mandala interpretation can be a process that takes many months or even years. Jung himself also looked at the mandalas he had created for a long time and contemplated them. It’s like a journey through the meanders of your own psyche. The point is to look at the mandala, think about how we perceive it, what we associate it with and why. To give the simplest example: if I put a yellow sun at the center, the basic questions I would ask myself are: how do I feel, what do I remember about the sun and the yellow color, and why have I returned to them now? Maybe I associate them with childhood, holidays, and being carefree, which I am missing?

Except that here we no longer rely on intuition, but we rationalize.

In the process of interpretation, there must be rationalization, because we refer to our memory and very personal associations. It is important not to start overinterpreting and rejecting the ready-made solutions that the internet offers us—we should not Google what a given color, symbol, or number of painted elements means because it will not bring us closer to interpretation, but take us away from it. It is best to just hang a mandala on the wall. Involuntarily resting our eyes on it, perhaps we will suddenly remember an event that will carry important information for us. The painting of the mandala itself is often just the beginning of the process.

And if no associations appear? Are we supposed to go with our mandala to a psychotherapist to help us interpret it?

If we are in the process of therapy, a specialist’s view can be helpful. However, the mandala leads us in a slightly different direction—towards looking for answers in ourselves. It seems difficult because Western educational systems, which to a large extent shape us, focus on ready-made, systematized solutions. And the mandala is simply looking at ourselves, just like meditation, during which no one explains the thoughts that appear in our heads.

To what extent do you have to be able to paint to be able to create a mandala?

In my opinion, there are no people who cannot paint. Again, this is just a matter of our own assessment. We are afraid to create because we assume that we will not meet the current standards of beauty, the canons imposed by art schools and academies of fine arts. Let’s remember how many painters gained fame precisely because they undermined the existing rules: Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, etc. In the mandala, we shift our attention from what others consider beautiful to what we want to express—to the beauty resulting from authenticity.

Can we create mandalas without delving into ourselves, for pure pleasure or rest?

Of course, mandalas are also fun and joyful! They can be a way to reduce stress. You can buy “anti-stress” coloring books, with ready-made templates. This is a kind of easier work with the mandala, we do not have to create its skeleton ourselves using a ruler, a compass, and a protractor, but we can still choose the colors and draw various elements. The impact on the psyche can be equally beneficial.

What about creating mandalas together? The collective arrangement of twigs, leaves, and flowers has become an element of the so-called forest baths: shinrin-yoku in Japanese; attentive group walks in the forest. What are the benefits?

In the East, where community rather than individualism plays a key role in people’s lives, mandala creation is often a collective process. It builds social bonds; the feeling that we are not alone gives support. A year ago, just after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, I was asked by one of the Warsaw cultural centers to conduct a workshop in which the inhabitants of the neighborhood and refugees from Ukraine would be able to create a blue and yellow mandala together, representing the colors of the Ukrainian flag. We gathered around a large canvas, which we put on the table and began to paint on together. Conversations about war and fear began over this work, and at times tears flowed. Our mandala was painted with emotion—it helped people express and experience them. To this day, it hangs in this cultural center.

So again: the ordering of chaos.

Chaos comes from outside, but it is inside that we have to somehow sort it out in order to be able to continue living in the face of increasingly difficult events. The mandala is a tool that helps in establishing internal order. No matter what you’re experiencing, you can stop, sit down, and paint it. In this sense, the mandala is like a self-portrait catching something extremely fleeting—a microcosm that each of us is.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Luiza Poreda:

A philosopher of art and cultural expert, for over twenty years she has been professionally involved in painting and drawing. For more than a decade, she has been creating mandalas, based on Jung’s method and surrealist automatic writing.