What a pretty little glass ball with a colorful swirl inside! Just like the ones I played with as a kid.

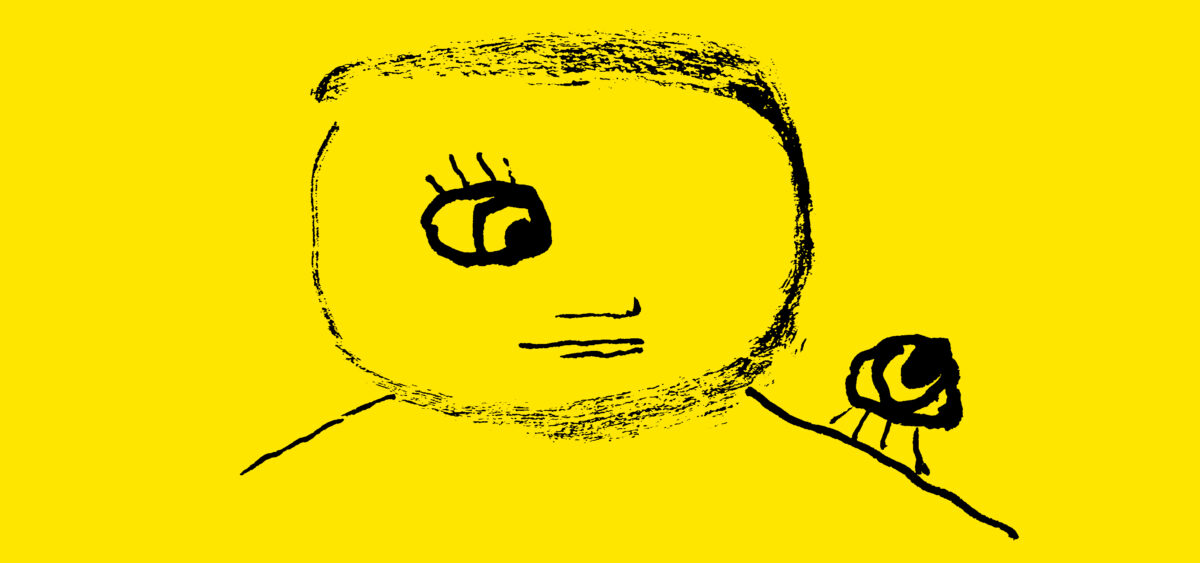

I’m so moved that I decide to pick it up from the pavement; I bend down, reach out my hand, and suddenly jump back. It’s not a glass ball, it’s an eye! Devious and taunting, an evil, evil eye! Oh, you nasty little eye! Do you think it’s nice to play pranks on passers-by? I’ll catch you and teach you not to play stupid tricks. But the eye escapes. It is agile and fast; it slaloms between pedestrians, dogs, streetlights, and trash cans, jumping manholes and curbs. I run after it and I know I have to catch it because some things simply can’t go unpunished. Then the eye stops. Instead of running away, it is casually pirouetting on the spot. Why? I look around, and suddenly I understand—I’ve fallen into a trap. I’m in a damp backstreet and there are no people around. But there are eyes everywhere, vicious and mocking. They’re sitting on windowsills, doorsteps, bricks, walls, and battered cars, and they’re all looking at me. So this is it. I’ve been cornered by the Eye Gang! What should I do? I squeeze my eyes shut as tight as I can, so as not to see those scornful looks. I put on dark glasses too, just to be sure. Then I take my harmonica from my pocket and play the most heartbreaking blues in the world. Every now and then, I take the harmonica from my lips and I sing: There’s no effect without a cause, All I see are ruts and flaws. The words are a bit odd, but that’s all I can come up with. I’m imagining the eyes being moved by my music, floods of tears spurting from each one so profusely that the whole gang is swept along and carried far, far away. But when I open one eye just a crack to see if I’m free, I realize how wrong I was. The crowd of eyes has grown, and they’re even more aggressive. Actually, that was to be expected. How could the eyes hear me? They don’t have ears, after all. I have to appeal to sight, not hearing. I take out my smartphone, wipe the screen and position it upright, leaning against a trash can. I open a flickering, colorful app and I can already see that I’m saved: all the eyes are staring at the screen as if hypnotized. They’re paying no attention to me. I cautiously make my way back toward the main street. As a farewell gesture, I’m tempted to give a little kick to the meanest eye that tricked me into coming here, but I don’t. I just leave. And now here I am by the river, admiring the clouds, and I still can’t believe that I managed to extract myself from the eyes’ ambush.