Watch out, Satan never sleeps! You can fall into his clutches anywhere and at any time, even in the holiday season. You’d better be prepared, so here’s our handy pocket guide to devils and demons for you to cut out and keep.

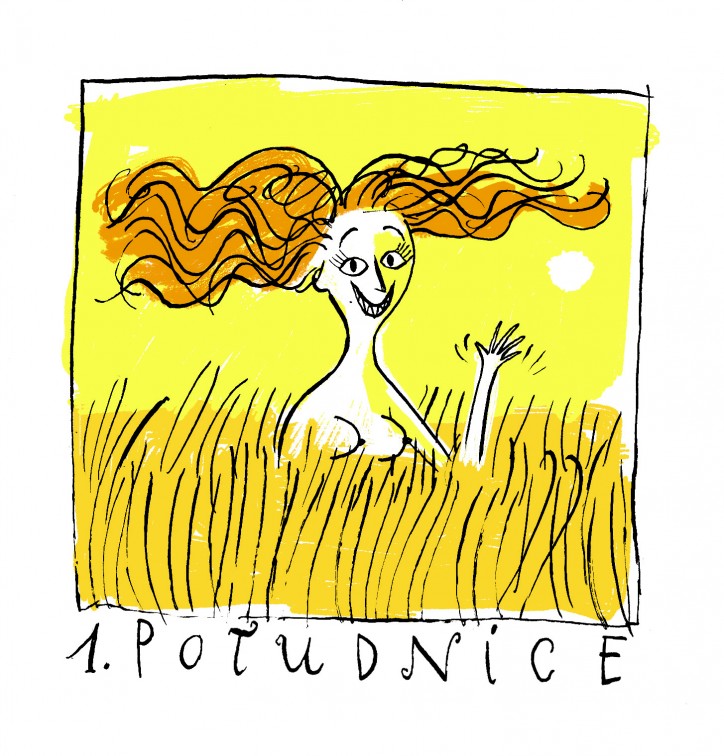

The Noon Witch

Slavonic demonology features plenty of ‘charming’ creatures, such as Baba Yaga (the hideous witch who flies in a pestle), Ovinnik (the evil spirit of the threshing house who sets fire to the grain), Utopiec (the water-dwelling spirit of a drowned man), Ćmok (a snake-shaped demon that lives in the corner of the cottage and is best not provoked) and Mamuna (the malign spirit of a woman who died in childbirth). In summer, you must be especially on the alert for Południca – aka the Noon Witch. Anyone who’s ever been on a long walk in Poland is sure to have taken a short break in a field, to get respite from the blazing sun beneath a tree. That’s just when the Noon Witch is likely to attack. She’s heralded by a whirling pillar of dust on the road, and a ripple through the cornfield (not to be confused with corn circles, which are left behind by more modern devils). Then a tall, thin woman appears with wind-tossed hair. She’s either very beautiful or extremely ugly. Wrapped in a sheet, she rises up in the air to spy out her victims. If she finds you asleep, she’ll strangle you or cut off your head with a sickle, as she has often done to harvesters.

In some regions, the Noon Witch preys on the lustful in particular, so it’s a good idea to avoid romping about in the corn or skinny-dipping in ponds and brooks. She doesn’t just attack adults, but if she catches sight of an unattended child, she steals it away in her sack or disfigures it. If you’re lucky, you might run into an