One of the more interesting things to come out of the various COVID-19 social restrictions is how much some people are happy to give in to the uncertainty. In this moment of suspended time, self-care is something to be indulged in and drawn out, whereas idleness and rest are possible without unduly compromising social relations. It’s a curious consideration for how we’re normally forced to live: if, in our day-to-day activities, there is no longer any room to be variable – with ups and downs and niggling health conditions – in this new space for idleness, our understanding of personhood is broadened; taking care of ourselves is no longer a matter of self-indulgence, only a normal part of life.

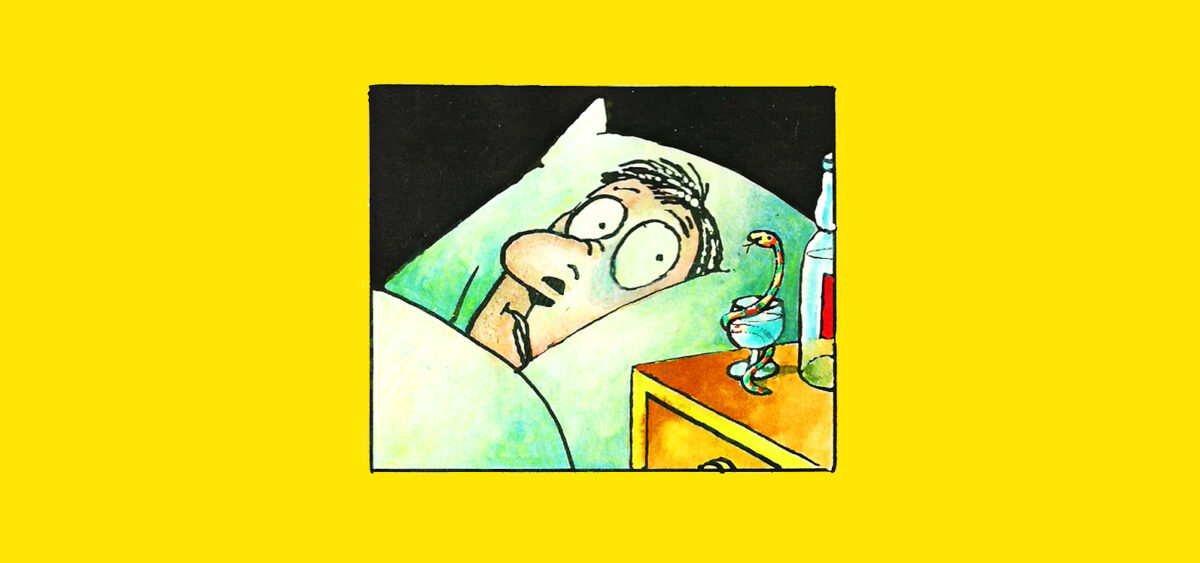

I think about this a lot, because in Poland there are still echoes of a different way of doing things, where being sick is a normal thing and there is room for infirmity and care. Whereas in Australia, where I grew up, the impetus was to push through and get on with it (so-called ‘presenteeism’), in Poland you’re allowed to just stand around complaining about your health for hours on end. What therefore appeared to be hypochondria in my family, turned out to be a gentle cultural rumination on the pitfalls of being a person. There is attention (friends will come over with chicken soup) and a pleasant sense of continuity (everybody swears by their grandmother’s