On this September day, the campus of Tufts University looks exactly like in those photos on the website gallery. Low brick buildings, lots of trees, sunshine lighting up small courtyards. Academic life seems to be going slowly; one could almost say lazily. Well-dressed, athletic young people wander around, talking, smiling. Some are sitting on benches and reading; others are holding hands or hugging in the midday glow. They are young and attractive, hungry for knowledge, full of dreams about a wonderful future.

Approaching the Center for Cognitive Studies, where I am to meet with Daniel C. Dennett – one of the greatest living philosophers – I cannot help but think that in somewhat similar surroundings lived a young prince by the name of Siddhartha, better known as the Shakyamuni Buddha. Everything around him was perfect. Wherever he looked, he saw young, healthy, beautiful people. That was because his protective father wanted to spare him any disturbing experiences, and banished everything that had to do with old age, illness and death. When Siddhartha finally discovered those things, he rejected his life and went on his way to find enlightenment. Does the Tufts campus also have some secrets?

It’s not as eccentric an association as one could think. After all, Dennett, just like Buddha, claims that our consciousness, our sense of ‘self’, the very thing that feels most real to us, is merely an illusion; something akin to a user interface on a computer screen. We wouldn’t call our computer desktop real. And what about the folders in which the files are kept? They don’t really exist; they’re only a graphical representation of complicated processes inside the computer. Same thing with our ‘self’. It is just like that folder – a result of a program installed in our brain by culture and language. A human being is therefore a creation of two evolutions: biological and cultural. The first is responsible for the development of hardware, the second is responsible for software. That’s all there is. No mysteries, no immortal soul, no divine spark.

Would Buddha sit behind a desk laden with books, newspapers, pictures of loved ones? Would he fish not far from his home in Maine? Would he be able to build a house with his own hands? Would he drink black coffee from a massive mug, publish books, present papers at conferences? Would he sometimes call people who don’t share his views “nuts”?

I don’t think so. Who, therefore, is this man, who 2500 years after Buddha claims that we are merely illusions?

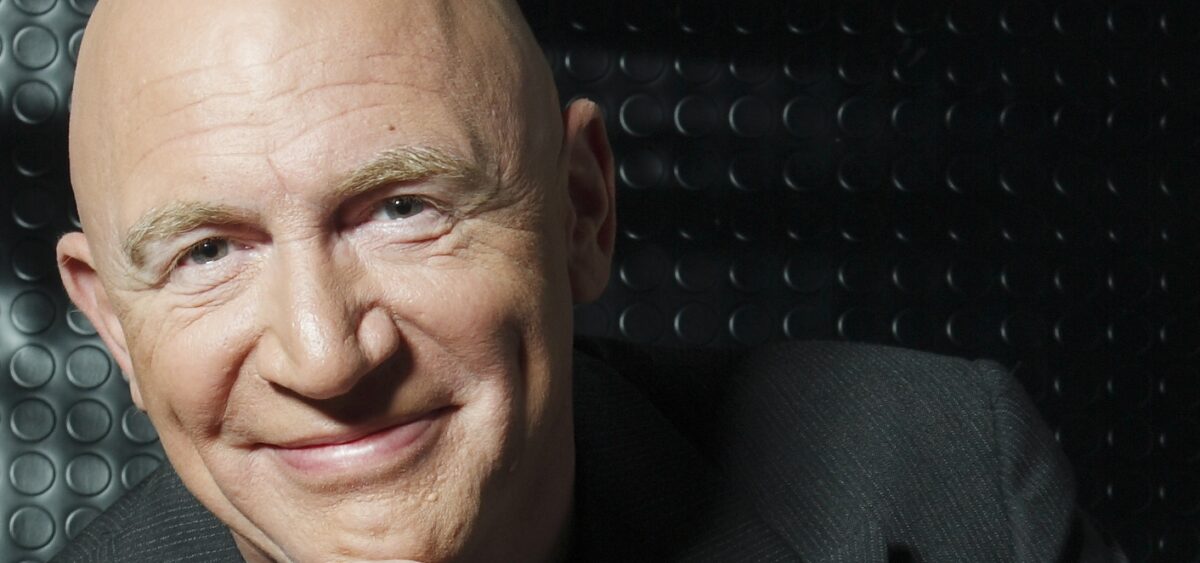

Judging from his massive frame, long silver beard, booming voice and massive hand, which he extends to me when we meet, I can say one thing for sure: Daniel Dennett exists and is real. Whatever else he claims on this subject.

Tomasz Stawiszyński: Who are you?

Daniel C. Dennett: In one sense I’m many people, but more or less unified into one professor of philosophy who spends more time these days with psychologists and computer scientists and evolutionary biologists than with philosophers. But I’m still a philosopher and I still have some big philosophical projects to work on.

I thought you would say that there’s no ‘you’ at all. You’re well known thanks to your statement that consciousness and the sense of self are merely illusions.

Yes, and people refuse to understand that. Many people simply can’t get their heads around what I mean by that. I obviously don’t mean that we don’t exist. We do. But then visual illusions exist as well – they just aren’t what people think they are. And what I’m calling “the user illusion” is in this sense a perfectly real phenomenon. It just isn’t what it appears