Between the fertile planes of Bengal and the waters of the Indian Ocean stretches an archipelago of green islands that disappear in the sea twice a day. Indians believe that only those pure of heart have a chance of surviving in the forest labyrinth of the Ganges Delta.

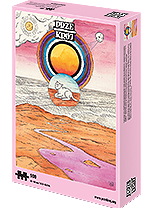

The darkness fades away an hour before sunrise. The sky turns pastel pink, quickly losing its hazy layer. The moisture hanging above the water will soon dissipate in the first wave of heat. The boats are sleeping, moored in the middle of the lake. At two minutes to six, a bright gold sphere peeks from under the thick wood. From now on, it all happens quickly. In just half an hour, the heat will be scorching.

From the huts deep in the island come the first sounds of life. The clanking of metal dishes, the splashing of people bathing in the ponds outside their homes, the cracking of wood in clay stoves. And the howl of conch shells, announcing the celebrations of the morning puja for the bloodthirsty goddess Kali, perseverant Vishnu, and Bonbibi, the goddess only worshipped in this region and the only deity in India recognized by both Hindus and Muslims. Bonbibi is the guardian of the forest, protecting her people from Dakshin Rai, a demon that presents himself as a man-eating tiger. The farmers pray to Bonbibi in little temples, recognizing her in every tree they pass, and in the earth they walk on. Those who live off the jungle – fishermen and beekeepers who take boats to the mangrove forest – touch the ground as soon as they reach the land, and perform a ritual expected to guarantee they come back safely. Bonbibi is the ruler of Sundarbans, an insular land by the estuary of the great Ganga River at the Bay of Bengal. The locals believe that cyclones and wild beasts obey Bonbibi’s every wish.

The salt of the earth

The calves moo, standing tied to lampposts and solar panels that the local government has installed in the village. The animals are waiting for green shoots and vegetable leftovers, soaking for them in plastic barrels. Around them, goats are roaming here and there, eating everything they can nibble on. Shiv Pada Tarafdar set the radio to full volume, as usual. He’s lonely and partly deaf, not much for him to do today. Still a month to go before the rice harvest season starts. And so he busies himself around the overgrown garden, wearing just a worn-out gamcha – a red-and-green checkered cotton strip tied around his hips. It’s the most modest of all clothing, which can also double as a towel or turban. Tarafdar’s knees are bothering him again. After 77 years of life filled with grubbing out trees, carrying bags of rice, shovelling dirt, and scooping out mud from the canals, his joints are ruined and degenerated, the same as for most people in rural Dayapur.

A blackened pot stands on a clay stove in the yard. It’s cold. Tarafdar has eaten nothing today. Since his wife left without a word five years ago to live in Kolkata with their older son, the man cooks for himself. It’s a shame to admit, but his children don’t try to stay in touch, so he won’t ask them for help. Years ago, he sold the family land to pay for their education. Now, to survive, he has to work in other people’s fields. He gets paid 250 rupees – three and a half dollars – for a full day’s work. His body is little more than a skeleton made of twisted bones. They press on his thin, darkened skin from the inside, as if trying to break free.

Przed zmrokiem nastaje drugi odpływ, z każdą minutą łódź przesuwa się wolniej, ostrożniej; zdjęcie: Paulina Wilk

Three houses further, a seven-year-old boy runs into the yard, carrying a bottle of water on his head. He sets it down on a roofed dirt floor in front of the hut, next to other containers that are already filled. The boy ran here from the tap that stands on the path crossing – a few years back, they had drinking water pipes laid here all the way from Kolkata. It tastes salty, but it’s safe for drinking. And what’s more important is that it is here at all. Before it came, all there was to drink was rainwater and a few dodgy wells.

The patter of the boy’s feet did not scare the cat laying in front of the house, feeding three white kittens. Behind the boy, his grandmother follows slowly, carrying a bigger bottle. Her name is Gauri, surname Mandal, like most people in the village. She is delicately built