“The night sky is the heritage of all humanity, which should therefore be preserved and untouched,” proclaims the resolution of the International Astronomical Union. Excess light affects not only the lives of humans, but also interferes with the functioning of animals and plants. We need darkness to survive, just as we need light.

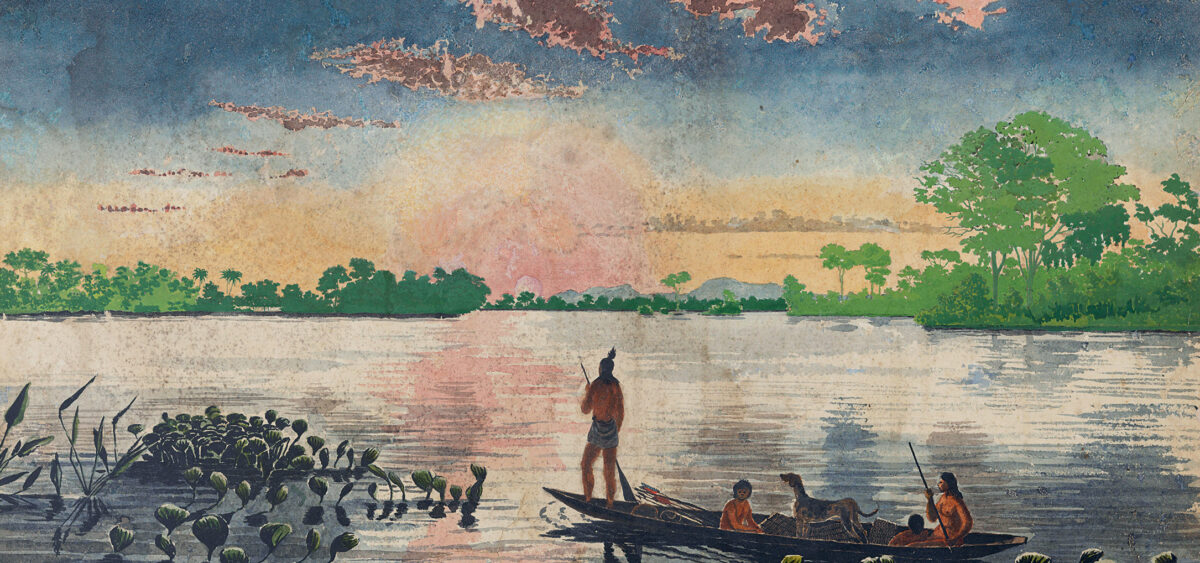

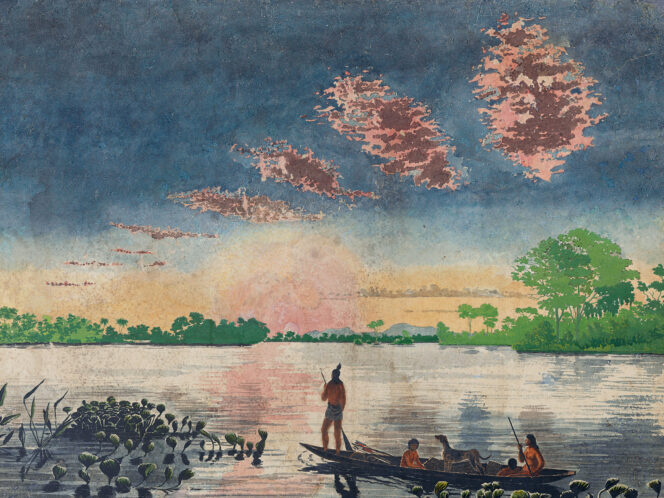

“When I think of dark nights, I think of this lake in northern Minnesota. On the longest day of the year, my father and I watch as the sun sets across the water and night begins filling a clear sky. Soon the Summer Triangle stands directly over us, Scorpio rises from the bay to the left. […] As a child I was afraid of night at the lake because the dark was so thick it seemed tangible […] like drapery. And the woods are still that way, but the sky is beginning to wear at the edges where gas stations hope to attract customers by immolating themselves in white light, and roadside restaurants blow their electricity bills straight into the sky. Each summer when I return to the lake I am no longer so much afraid of the dark as I am afraid for the dark,” wrote Paul Bogard in his essay published in the collection Let There Be Night: Testimony on Behalf of the Dark. Bogard, who is a professor of creative writing at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, was one of 28 authors explaining how important darkness is for humans. This isn’t Bogard’s first book on the topic. Five years ago, he wrote The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light, where he explained how an excess of light can affect and disrupt the functioning of humans, animals and plants. “Just as we need light, we also need darkness to live,” he argues.

Shedding light

To, as it were, shed s