Gazing through dust

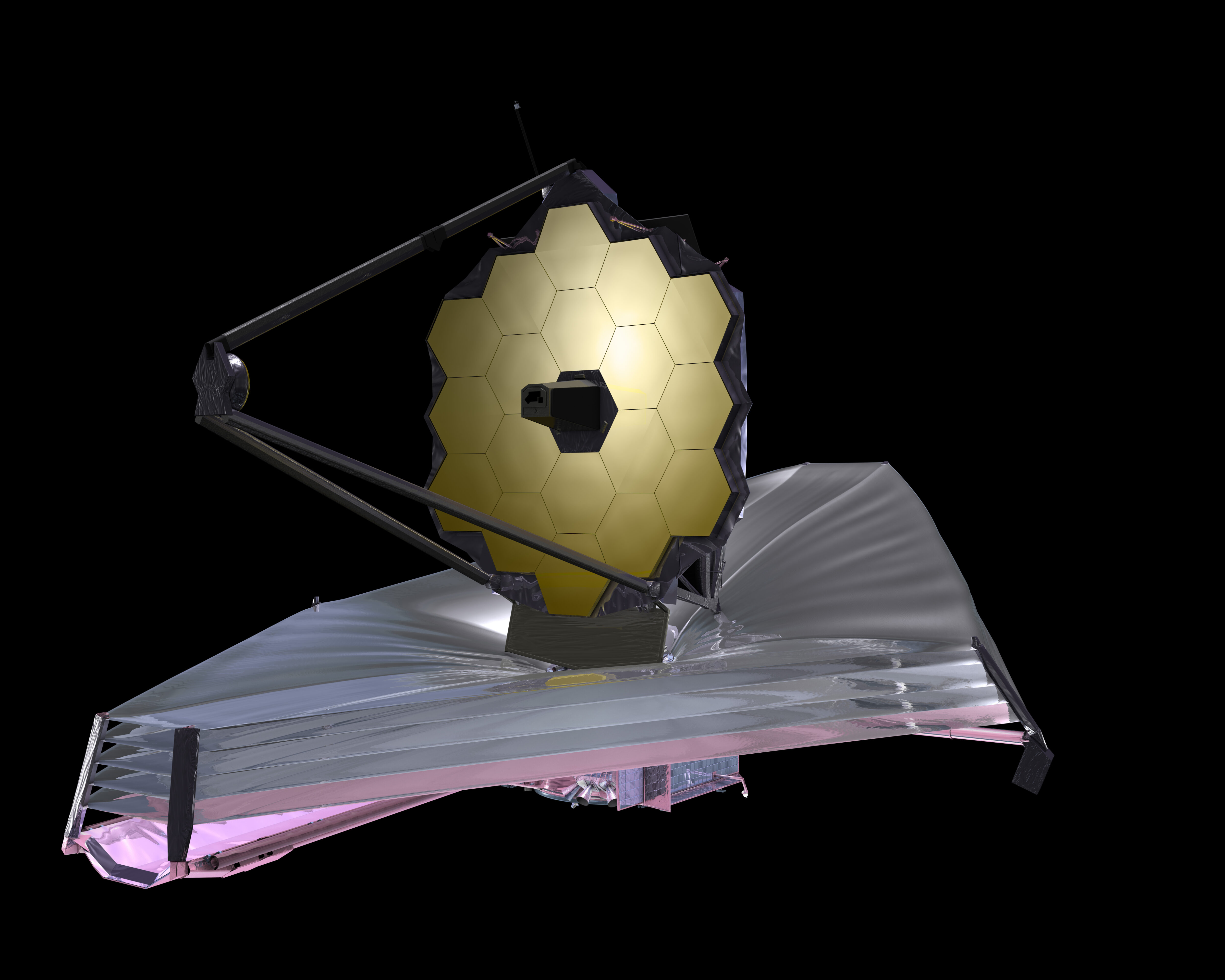

At the very end of 2021, after many grand announcements, the James Webb Space Telescope was launched into space. It is deemed a successor of the Hubble Telescope, but while Hubble is sensitive mainly to visible light and to ultraviolet, Webb will photograph space mostly in infrared.

Scientists picked this particular band of the spectrum for important reasons. Visible light does not penetrate the so-called dark nebulas, of which there are heaps in space, but infrared does. The situation is similar with the clouds of cosmic dust that surround emerging stars and planets. In visible light we can only see the dust, while in infrared we see whatever the dust conceals. This is also the case with the cloud enveloping the centre of the galaxy.

Infrared is also advantageous when using a spectrometer to analyse the composition of the atmosphere of distant planets. Another task that suits this band well is observing the oldest parts of the cosmos. The universe is expanding and its furthest, oldest regions are receding ever more quickly: what follows is