“The road began to climb more steeply. Sun and heat. These are still the Maritime Alps, but increasingly mighty. It’s like swimming far out to sea: near the shore the waves are short, sharp, irregular – beyond they become longer and higher. It’s the same now with the mountains.” So begins the diary entry for one of Andrzej Bobkowski’s wartime bicycle trips through occupied France.

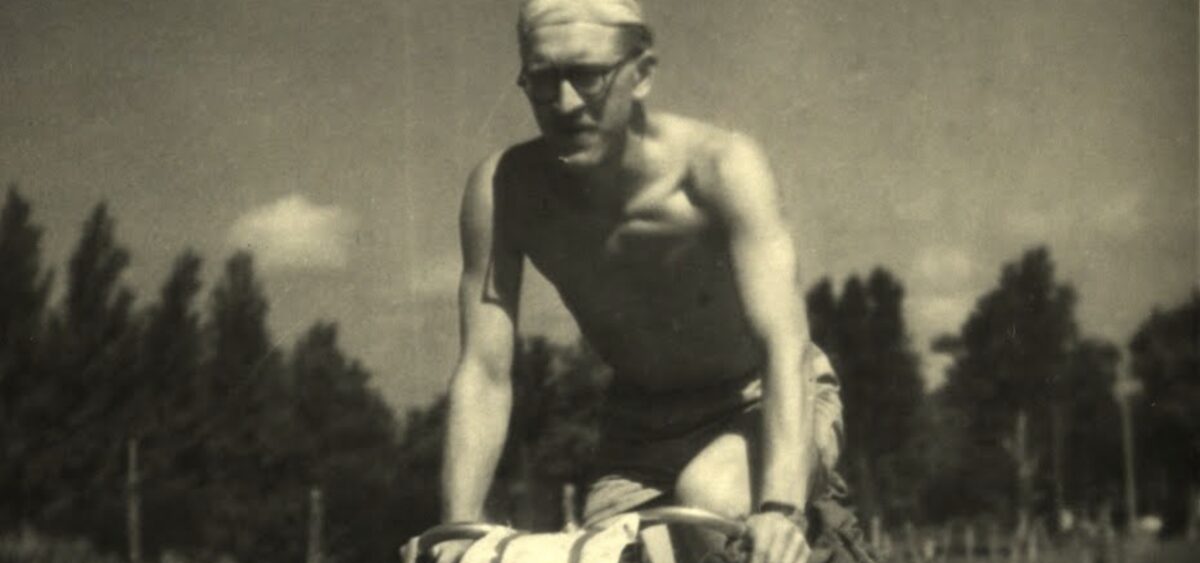

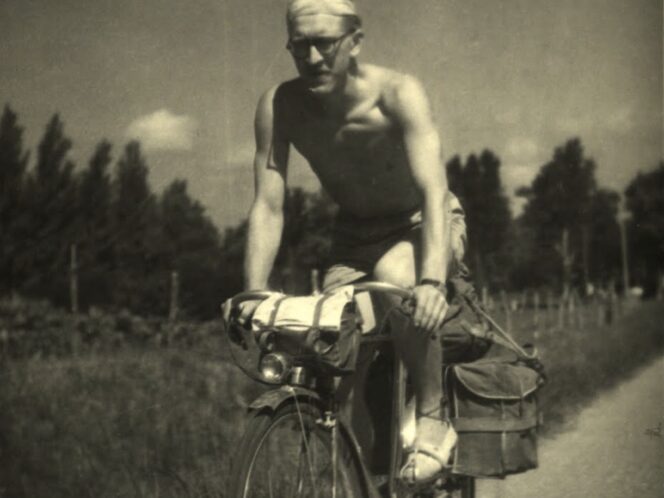

Andrzej Bobkowski left Poland for Paris in March 1939. A 26-year-old graduate of economics, he was to take an internship arranged by the Polish Ministry of Commerce and Trade. This, however, was not to be. A couple of months later, on 1st September 1939, Poland was invaded by Germany and less then a month later ceased to exist. On 10th May 1940, the Germans invaded France. 10 days later, Bobkowski started writing his wartime notebooks, which he would continue until August 1944, when American soldiers liberated Paris. After the war, Bobkowski would not return to the now-communist Poland. Instead, he boarded a ship bound for Guatemala, where he settled. For the rest of his life, he ran a shop selling airplane models (his life-time passion), writing occasionally.

In the excerpts, below we follow Bobkowski on his bicycle trip from southern France back to occupied Paris. The route – taken in full gear and provisions, and in the company of a Polish worker named Tadzio – had become a chance to encounter local people and to enjoy the pleasures of rural life. But it also offered a fresh and critical look on the foundations of European culture, which had led to war.

September 6, 1940

So we set out. Yesterday afternoon we packed almost everything. Today we rose at six and finished our preparations. Our friends left to catch a train leaving for Toulouse at a little past seven. Tadzio and I remained alone in the room, as on a battlefield. We were sorry to leave. We had grown fond of the hotel, the room, the people, of everything. And now simply to leave it all behind.