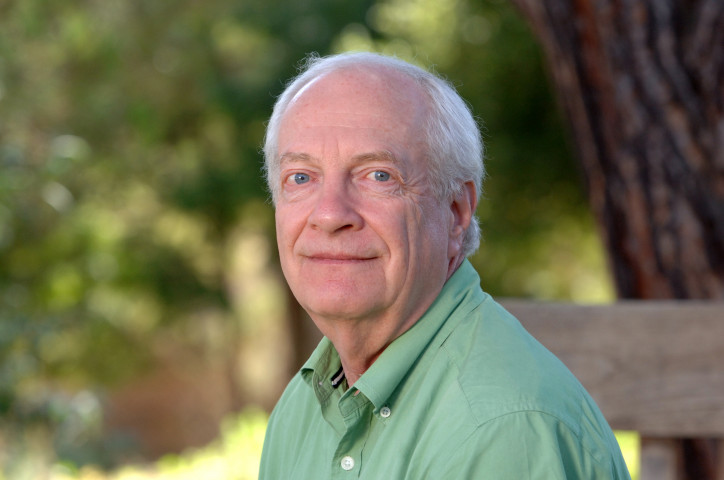

It all began with an overbooked flight, which led to me flying to New York on the Tuesday instead of the Monday. I didn’t really quarrel with LOT Polish Airlines, because my meeting with Allan Horwitz – whom I had been waiting for years to interview – was scheduled to take place on the Wednesday. Horwitz is one of my intellectual idols; I devoured his books The Loss of Sadness, What’s Normal? and Creating Mental Illness. Anyhow, I e-mailed the hotel to let them know that for unforeseen reasons I would be arriving a day later.

However, when I finally arrived at the hotel the following day, after a three-hour long drive (because of extremely, even for New York, heavy traffic), I was completely jet-lagged and knackered. If this wasn’t enough, it turned out that they had never received my e-mail and thus my booking had been cancelled. “We don’t have your room and there’s nothing you can do about it” is more or less what I heard from an extremely unfriendly receptionist.

With nothing else to do, I headed off in search of a new room. This took me another three hours. Unfortunately, a huge ventilator installed next to the window – a hellish device, which kept buzzing even after I pulled the plug out – prevented me from getting any sleep at all.

Despite all this I tried to stay confident, and on Wednesday morning I walked to the Port Authority Bus Terminal to catch a bus to Princeton. After spending a few minutes in a building that looked as if it was taken straight out of Franz Kafka’s nightmares, I just wanted to run away. Hundreds of platforms, thousands of people rushing to different places. A crowdy, noisy and chaotic place. Which bus am I supposed to get on and where should I go?

Finally, I managed to board the bus and get to the meeting point. After 36 sleepless hours, I managed to arrive at the porch of a lovely, wooden villa. I was exhausted and sweaty because of the horrible heat and the humidity in the air… there’s no doubt that I could have looked exactly like your everyday eccentric. Yet I also wouldn’t have been surprised if, as a result of the previous day and a half, I was just hallucinating and, after opening his front door, Horwitz didn’t actually look at me with a hint of surprise, or even concern.

It is common knowledge that the best way to divert attention away from one’s own mental state is to become interested in the interviewee’s mental state. This works especially well if the interviewee is a prominent sociologist, who on a daily basis deals with such concepts as illnesses, health, disorders and norms. Which is why once we sat down in the living room, I immediately cut to the chase.

Tomasz Stawiszyński: Do you consider yourself a normal person?

Allan Horwitz: Oh, absolutely not [laughs].

It’s not a surprising answer.

Obviously, the term ‘normal’ has a large range of applicability, but – let me back up – in the way that I would define normal, then yes I would say, I’m normal; normal meaning not disordered. I don’t think I’m disordered, so therefore I would consider myself normal. But if normal means typical, or statistically normal, then absolutely not.

What is your understanding of the term ‘disordered’?

Well, we talk about mental disorder and normality – but there’s clear cases on both sides, with sort of a broad fuzzy area in between. So while it’s possible to define clear cases, most cases probably don’t totally fit that. I think that clear cases would indicate that there’s some sort of dysfunction in a natural apparatus – and that natural apparatus could be perception or motivation or cognition or emotions – which prevents a person from acting