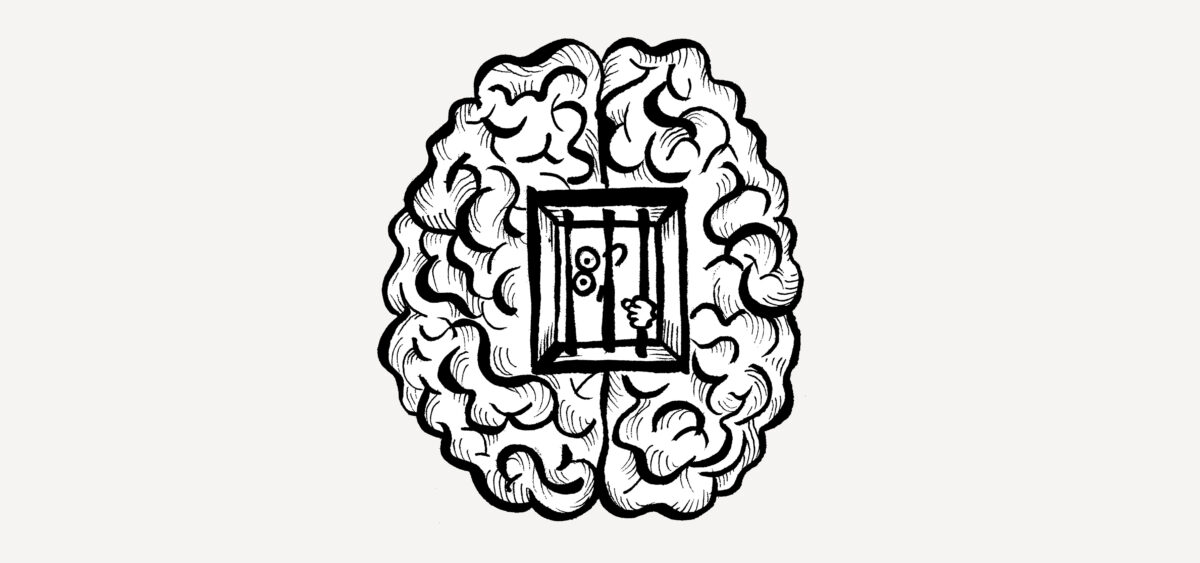

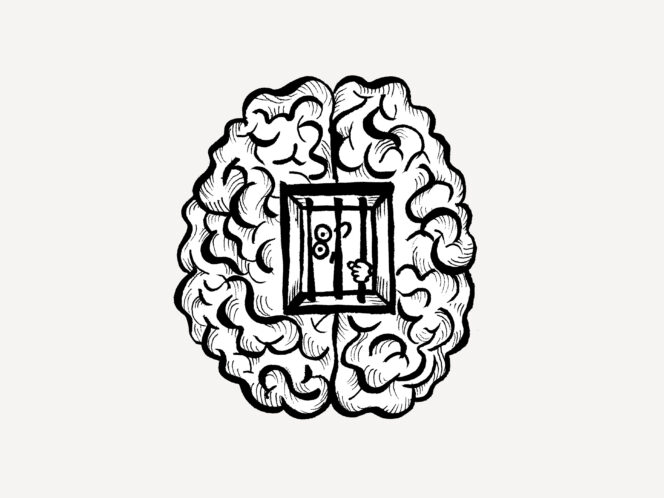

It performs nearly 40 million operations a second and has a tendency to control everything. In addition, it is stubborn and, since the Pleistocene era, has not changed its habits: persistently fantasizing about the bad things that might befall us. It’s worth knowing how to calm our minds so that we can rest from worries and overstimulation.

The most complex machine on Earth looks like a giant walnut. It is an unappetizing grey colour and has the consistency of jelly. It weighs just over one kilogram. It performs 38 million operations a second but, being an environmentally-friendly product, it consumes barely 12.6 Watts per hour (way less than the weakest lightbulb). Moreover, it uses exclusively green energy – it is powered by oxygen and glucose.

Many aeons ago, this pinnacle of natural engineering was already recognized as perfection. The last modifications to the design were implemented some 50,000 years ago. Since then, the human brain hasn’t changed. There is no reason for it to do so: this unprecedented evolutionary success is proven by its achievements. It has settled all the continents. A few copies have stood on the Moon, and one even made a parachute jump from the stratosphere.

This success wouldn’t have been possible without the external layer of the brain – the brain cortex. It has grown in humans, reaching an unprecedented thickness of two to four millimetres. In order to fit into the skull, it curled up into folds. The only place it couldn’t be tamed was behind the forehead, which expanded and straightened out, in order to accommodate the youngest evolutionary part, the frontal cortex.

It was worth it because, in fact, it is the frontal cortex that distinguishes our brains from all the other brains roaming the Earth. Thanks to the frontal cortex, without getting out of our armchairs, we can imagine what Felix Baumgartner felt as he stood on the edge of the Zenith stratospheric balloon. We can count backwards from 138 in threes and can visualize for ourselves attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion, and then write our own fantasies, striking the keyboard with 10 fingers. Empathy, imagination, mathematical and logical skills, and the advanced motor movements of the hands – we have the frontal cortex to thank for it all, as well as the impossibly complicated symphony of chemical and electrical signals that make up the work of the brain.

There’s no need for modesty here: