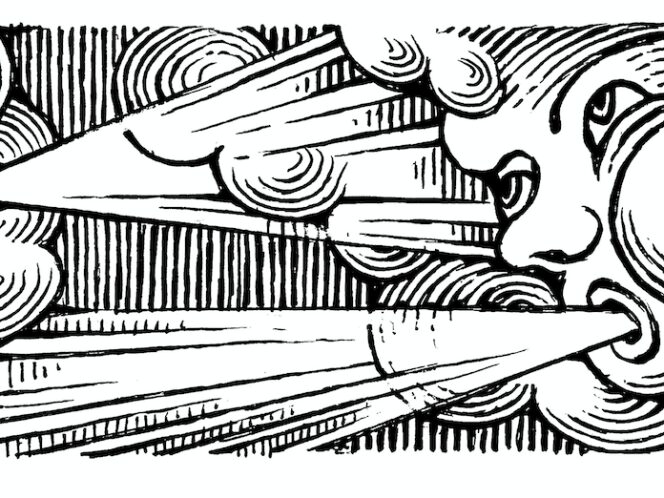

Breathe in, breathe out. Let us breathe with relief: the pneuma unifies us humans and the universe, guiding us wisely. That is of course, if you believe ancient philosophers.

The blurred figures of a few, semi-legendary great thinkers active in the 6th century BC in Greek cities on the Aegean coasts of Asia Minor loom over the beginnings of the philosophical reflection of our cultural milieu. Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes (all three of Miletus), Xenophanes of Colophon, and Heraclitus of Ephesus gave rise to intelligent reflection upon the world and human existence. What they also have in common is their search for the basic element, the so-called arche, from which everything in existence originated, and which is present in everything. To put it in slightly simpler terms and to avoid complex discussions, this element was, for example, water for Thales and fire for Heraclitus. Here, however, we are interested in Anaximenes, about whom we know little more than that he was most likely a pupil of Anaximander and was active in Miletus. Anaximenes was the author of a philosophical tractate praised for its clarity and simplicity of argument, but unfortunately this text