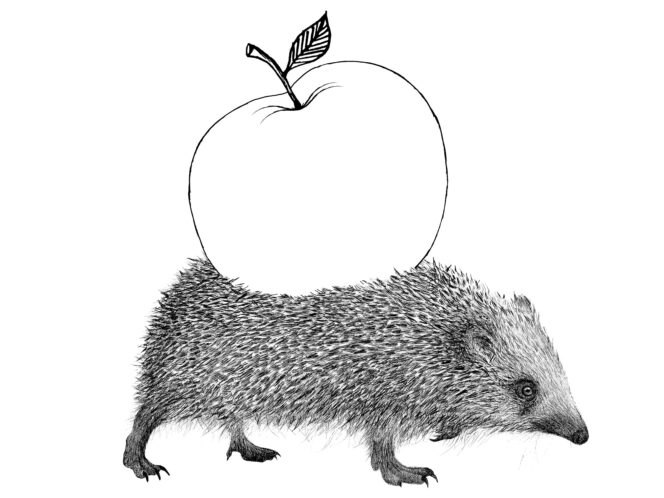

In many parts of Europe, the image of a hedgehog with an apple on his back is an iconic one—but in fact, the pleasant picture belies a long history of negative associations with the little animal.

In ancient times, hedgehogs were revered. In the seventh century BC, Archilochus of Paros appreciatively claimed that “the fox knows many things, whereas the hedgehog knows one big thing.” In stark contrast with the fox’s cunning and shifting attack strategies, the hedgehog remains true to its defensive tactics. It is an efficient and consistent creature that avoids unnecessary conflict. Three hundred years later, Aristotle praised hedgehogs for their ability to predict the weather. He believed they entered their burrows from different directions depending on anticipated changes in wind direction. The animal’s ability to defend itself against much larger predators aroused widespread sympathy, and the creature was featured on Greek vases and in Egyptian funeral paintings. Ancient Egyptians knew the dietary needs of these animals: in a tomb in Sakkara, there is an image of a hedgehog chewing on a cricket. Unfortunately, Pliny the Elder did not have the same knowledge. The Roman encyclopedist who lived in the first century incorrectly attributed specific behaviors to these animals and thus built a black legend that survived centuries.

The image of a hedgehog with an apple on its back has become a common one in many parts of the world where hedgehogs are found in the wild. So common that without the apple, the animal seems somehow incomplete. This is precisely an element of the long shadow of Pliny’s error. “Hedgehogs also lay up food for the winter; rolling themselves on apples as they lie on the ground, they pierce one with their quills, and then take up another in the mouth, and so carry them into the hollows of trees,” noted