It has a bakery, a hairdresser, a farm with eco-friendly food, and even a playground for children who visit. The inmates can set up their own companies, and some even have the right to go outside. This is how Uruguay’s most progressive prison looks.

Ahead of me are just two little towers. They’re empty. The soldiers only stand on the ones by the wall, which looks more like a concrete fence. The only police I pass are leaning on a car, bored. There are 10 police. And more than 600 prisoners.

Up until 7pm, the inmates are almost free. They bake bread and cakes, tattoo each other, cut hair, learn maths, plant cabbages, build kayaks. They prepare the next editions of a newspaper, radio shows, or rock performances. They finish high school; some of them finish university. They play football (in Uruguay a prison football league has been playing for decades; the prisoners tour by bus). They box, practice yoga poses, and study new roles – for theatre performances, but also for the new lives that will start when they leave the walls of the prison.

Welcome to Punta de Rieles.

A start-up loan

I meet the warden early in the morning, in front of a bank in central Montevideo. He smells of mate and alcohol. Yesterday Uruguay played Ecuador. José Luis Parodi has just registered more companies for his inmates and opened bank accounts for them. Punta de Rieles is home to 38 such companies – each of them received a start-up loan from the facility. If the business survives, repayment starts after three months; the prison takes 10% of the company’s monthly earnings. “It’s the only fund in the world that lends interest-free, and the borrower can’t go to prison, because he’s already there,” Parodi jokes.

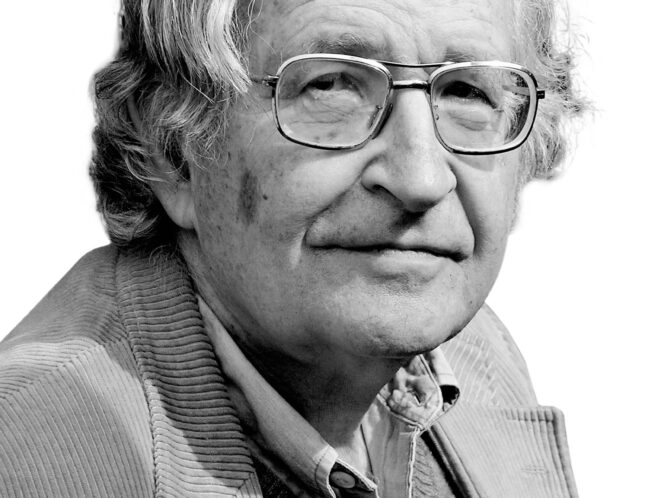

He’s tall, tanned, pugnacious. We drive to the prison, on the outskirts of the capital.

“Every person acts with