Androids may dream of electric sheep, but Soviet cosmonauts dream of flowery meadows and white birch tree-trunks. Fortunately, there was someone who painted their dreams and sent them along up into space.

The Soviet space-exploration dream left its mark in various forms. There are monuments and streets named after Yuri Gagarin in most cities and towns, numerous Cosmonaut Avenues and Cosmonaut Boulevards, countless statues of rockets and sputniks. There are space-themed murals and mosaics on buildings and bus stops, as well as sports venues and brutalist-style circus buildings shaped like flying saucers. There is also science-fiction literature, electronic music played on Soviet analogue synthesizers that once blasted from speakers in parks and department stores, and children’s films such as Visitor from the Future and Adventures of the Electronic. There are all the posters, stamps and pennants you can still find at any of the Russian barakholki, or flea markets. In the early 1980s, smoke-enwreathed dance floors were filled with dancers bopping to the hit of the band Zemlyane (meaning ‘Earthlings’): “Earth in the viewpoint that I see / Like a son missing his mother / We miss our Earth – we have but one […]”.

Meanwhile, behind this façade of pop-culture, hidden away in top-secret, closed-off zones, space scientists and engineers were busy working on important projects. The cosmonauts, although heroes and idols of the masses, were under constant pressure – space travel and preparing for it were both physically and mentally exhausting. They didn’t really have much of a say. How could they complain? After all, they were the chosen ones. During his first flight, Yuri Gagarin made the best of Spartan conditions, but someone had to blaze the trail for others.

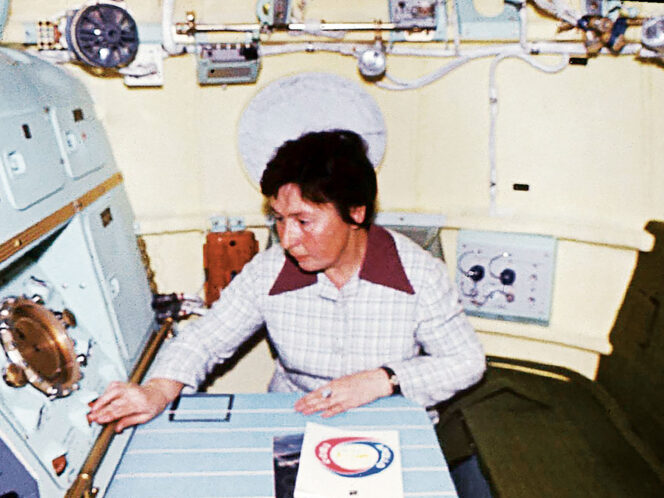

When preparations began for longer trips into space, a young graduate of the Moscow Department of Architecture, Galina Balashova, arrived at the Rocket and Space Corporation Energia (RSC Energia) near Moscow, the training ground for space teams. She was the only woman to join the team, brought in by Sergei Korolev, the greatest Soviet authority on spacecraft and rocket design.

Balashova clearly recalls that Korolev was the only one who understood that, apart from machinery to keep them alive, cosmonauts also needed some kind of private space and basic creature comforts. A home-away-from-home with simple furnishings and a comfortable toilet; bright colours to soothe the mind of a person who had been hurled out into the dark and cold cosmic vastness.

But how could they fit all that into a limited spherical space where the law of gravity doesn’t apply? Balashova puzzled over this while working after hours, as her official tasks were much more mundane: dealing with renovating the facilities and greening up the premises. In addition, she had been a watercolour painter ever since she was a child, painting landscapes of her native Moscow Oblast. “And we dream not of thunder at the cosmodrome / Not of the ice-cold blue of the sky / But we dream of grass – the grass beside our house / Green, green grass”. While the whole country was singing along to this Earthlings hit, nobody realized that in a space-town in the suburbs of Moscow, someone was painting melancholy pictures for the cosmonauts, of birch trees reflected in forest lakes. And that one day these paintings would end up destroyed along with the space capsules descending somewhere on the steppes of northern Kazakhstan.

The artist would have remained anonymous to this day, if not for the German architect Philipp Meuser, a specialist in modernism and an aficionado of retro-futurism. While digging around the depths of the Russian internet in 2012, he found sketches of orbital modules designed by Balashova, became fascinated with them and launched a private investigation. Shortly after, he found himself in a Moscow suburb, standing in front of a worn-out ‘Khrushchev building’ (a four-story structure for housing workers, dating from the Khrushchev era), where a grandmother in her eighties lived with her family. A retired space designer whose name meant nothing to anyone in Russia, but who was soon to be hailed as a pioneer of cosmic interior design.

Meuser paid homage to Balashova in the form of a richly-illustrated album entitled Galina Balashova: Architect of&nbs