Breaking news, out-of-control teleprinters, and a world-wide network of knowledgeable computers are at the centre of this short story by the master Stanisław Lem. Discover how the story ends in Part III of this truly surprising mix of sci-fi and supernatural horror!

Hart usually arrived at about three, with a file stuffed with papers, and a thermos full of coffee, and got down to work, while I felt taken for a ride, but what on earth could I do, when objectively he was right? I went on thinking in my own way, falling into the ruts of the notions available to me, and thus for example I imagined that the world of previously lifeless objects—supply lines, undersea telegraph cables, television aerials, maybe chicken-wire garden fences, the arches and cramps of bridges, rails, winches, the metal bars set into concrete buildings—that all this, on an impulse from the network, undergoes a sudden amalgamation into one gigantic surveillance system, which my IBM conducts for a set number of seconds, because a couple of trivial accidents have led to it becoming the crystalizing center of this power. But even these delusions of mine did not even foggily explain the astonishing and specific details, such as a talent for predicting events, or its two-minute limitation—so I had to force myself to keep quiet and be patient, because I could see that Hart was giving it his all.

I shall move on to the facts. Hart and I discussed two things—the practical applications of the effect, and its mechanism. Despite appearances, the practical prospects of the one-hundred-and-thirty-seven-second effect are not especially great or significant, but merely have the remarkable quality of a spectacular performance. Decisions that prejudice the fates of nations and the course of world history generally do not fit in an interval of two minutes, on top of which a two-minute prediction of the future runs into an obstacle that seems secondary but is in fact fundamental: in order for the computer to start making those infallible prognoses, first it has to be set on a defined track, it has to be steered, and that takes time, usually more than two minutes, so in practical terms, most of the gain is immediately wasted. The limits of prediction cannot be shifted by a fraction of a second. Hart supposed that this was a constant, of a universal nature, though not yet known to us. One could probably have fun breaking the banks at major gambling houses, thinking of the profits to be gained from roulette, for example, but the cost of installing the relevant equipment would not be small (an IBM costs over four million dollars); organizing two-way communication, carefully concealed too, between the gambler at the table and the computational center wouldn’t be an easy nut to crack either, not to mention the fact that others would soon realize that something strange was going on—in any case, this way of using the effect did not interest either of us.

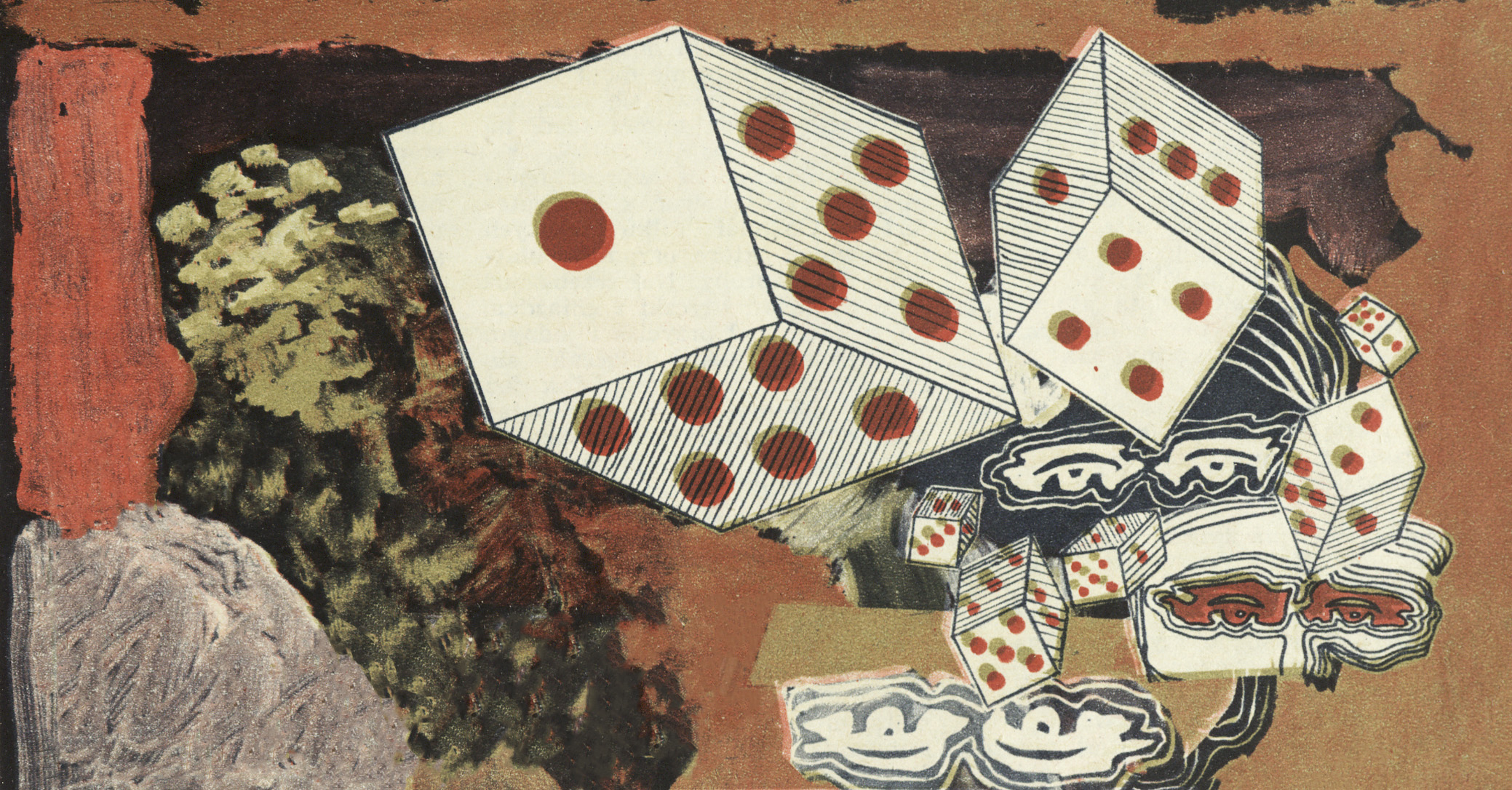

Hart drew up a piecemeal catalog of our computer’s achievements. If you were to ask it about the sex of a child who was going to be born in two minutes from now to a particular woman in a specific place, it would know that sex unerringly, but it would be hard to regard a prediction of that kind as worth the bother. If you started tossing a coin or throwing a gambling die, feeding the computer the initial results of a series of throws, and then you stopped giving it information, it would calculate the results of the next few throws for one hundred and thirty-seven seconds into the future, and that was all. Of course, you really did have to throw that die or coin, and give the computer result after result, at least thirty-six to forty of them, which was very much like guiding a dog onto the right track, one of billions, because at that same moment, God knows how many people were throwing coins or dice, and within all those throws, the computer, which was deaf and blind, had to identify your series of them as the only one that mattered. You also really had to throw the die or coin. If you stopped throwing it, it would type out nothing but zeros, and if you only threw it twice, it would only give those two successive results. To do this, it also had to have a connection with the network, although common sense would say that it couldn’t be of any assistance, as you were throwing the die two steps away from it—so what could the network have to do with it? Everything—in the sense that when disconnected from it, the computer could not stammer out a syllable, and nothing—in the sense that we did not understand this connection. Notice that the computer knew in advance whether or not you would throw the die, and so it predicted the development of the entire situation—that is, not just the fate of the die, meaning which surface would fall face up, but also your personal fate, at least within the limits of your decision whether or not to throw the die. We also did tests where I decided to throw six times in a row, for instance, and Hart was to frustrate or enable me alternately, without me being aware of his decision for each given throw. It turned out that the computer knew in advance not just my throwing plan, but also Hart’s intentions—in other words, it knew when Hart was planning to grab me by the hand holding the cup to stop me from making the next throw. One time, I was planning to throw the die four times in a row, but I only did it three times within the relevant interval, because I tripped over a cable lying on the floor and failed to throw the die in time. But somehow the computer predicted that I would trip, which was a complete surprise to me, and so at that point it knew far more about me than I did myself. We devised some much more complicated situations, in which a number of people would take part simultaneously—for example, leading to a genuine fight over the cup containing the dice, but we didn’t try these alternatives because they required time and bother that we couldn’t afford. Instead of a die, Hart also tried using a small device within which the individual atoms of an isotope disintegrated, causing flashes—so-called scintillas—to appear on a screen; the computer was unable to predict them more precisely than a physicist could have done—that is, it only gave probabilities of disintegration. This limitation did not apply to the dice or coins, clearly because they were macroscopic objects. But within our brains, it is microscopic processes that determine our decisions. Evidently, says Hart, they do not have a quantum nature.

Within the picture as a whole, there seemed to be contradictions. How could the computer predict that I would trip in two minutes’ time, making this forecast when I myself was not yet aware that I would take the step that would cause me to trip, while at the same time it could not foresee which atoms of a radioactive isotope would disintegrate? According to Hart, the contradiction was not in the events themselves, but was a property of our notions about the world, and especially about time. Hart figured that it is not that the computer predicts the future, but that we are in some peculiar way limited in our perception of the world. These are his words: “If you imagine time as a straight line, stretching from the past into the future, our consciousness is like a wheel that’s rolling along that line, always touching it at just one point; we call that point the present, which immediately becomes a bygone moment, and gives way to the next one. Research done by psychologists has shown that what we take to be the present instant, deprived of any temporal stretch, is in fact a tiny bit extended, and covers slightly less than half a second. So it’s possible that contact with the line that’s represented by time could be even wider—it could be in contact with a larger stretch of it at once, and the maximum size of that stretch of time could amount to one hundred and thirty-seven seconds.”

If that is really so, says Hart, then all our physics remains anthropocentric, because it arises from suppositions that do not matter beyond the scope of the senses and awareness of a human being. This would mean that the world is different from what physics says about it today, and clairvoyance, meaning predicting the future, whether electronic or not, never occurs. Physics has awful trouble in relation to time, which according to its general theories and laws really should be perfectly reversible, but isn’t at all. Additionally, the issue of measurements of time on the scale of intra-atomic phenomena brings up various difficulties; the smaller the time interval to be established, the greater the problem. Perhaps this arises from the fact that the concept of the present is not only as relative as Einstein’s theory says it is, in other words, it is dependent on the localization of the observers, but it also depends on the scale of the phenomena occurring in the same “place.”

The computer simply remains in its physical present, and this present is more extended in time than ours. Something that for us is about to happen in two minutes from now, for the computer is already going on, in the same way as for us whatever we are now perceiving and feeling is happening. Our consciousness is just a particle of everything that occurs in our brain, and when we decide to throw the die just once, to “fool” the computer, which is tasked with predicting an entire series of throws, it immediately finds out. How does it do that? This we can only imagine by applying some primitive examples: the lightning flash and thunderclap of atmospheric discharge are simultaneous for the observer, but occur at different times for the more distant one; in this example the flash is my decision, taken in silence, to stop throwing the die in about fifteen seconds, and the thunder is the moment when I actually fail to perform the next throw; so in some unknown way the computer is able to catch from my brain the “flash,” that is, the taking of that decision; according to Hart, this has important philosophical consequences, because it means that if we have free will, it extends only beyond the limits of one hundred and thirty-seven seconds, except that from introspection we are unaware of any of this. Within the scope of those one hundred and thirty-seven seconds, our brain behaves in the same way as a body that is moving torpidly and cannot abruptly change direction; for this to occur, the time is needed in which a force will act that alters its trajectory—and something like this happens inside every human head. Yet none of this concerns the world of atoms and electrons, because there the computer is just as resourceless as our physics. In Hart’s view, rather than a line, time is a continuum, which on the macroscopic level has completely different properties from “down below,” where there are only atomic dimensions. Hart supposes that the larger a particular brain or brain-like system, the wider the extent of its contact with time, in other words, with the so-called present, whereas atoms do not actually come into contact with it at all, but keep dancing around it, so to speak. In short, the present is something like a triangle: pointed at the top, where there are electrons and atoms, and widest at the base, where there are large bodies gifted with consciousness. If you say you haven’t understood a word of this, I can tell you that I do not understand it either, and what’s more, Hart would never dare to say such things in a lecture or publish them in an academic journal.

I have actually told you everything I planned to say; all that I have left are two epilogues, one factual, the other a sort of grim anecdote that I will let you have gratis.

The first one was that Hart persuaded me to let the professionals take the matter in hand. One of them, a senior figure, told me a few months later that after dismantling and reassembling the computer, the phenomenon could no longer be recreated. I didn’t find this suspicious, so much as the fact that the specialist to whom I was talking was in uniform, and also that not a single syllable of the matter got into the press. Hart himself was soon removed from the research. He didn’t want to bring up the subject either, and just once, after a victorious game of mahjong, quite out of the blue he told me that one hundred and thirty-seven seconds of unerring prediction was in certain circumstances the difference between the annihilation and the salvation of a continent. At that point he came to a stop, as if he had bitten his tongue, but as I was leaving his place, I saw on the desk an open volume, larded with mathematics, of a work about missiles that intercept nuclear warheads. Perhaps he was thinking of the sort of duel fought by these missiles? But that’s just my conjecture.

The second epilogue happened just before the first, literally five days before the invasion of the swarm of experts. I’m going to tell you what occurred, but I shan’t pass comment, and I refuse in advance to answer any questions. We were now working on the last of our solo experiments. Hart was going to bring a physicist to my shift, who was under the illusion that the one hundred and thirty-seven effect had something to do with the mysterious number one hundred and thirty-seven, apparently a Pythagorean symbol of the basic properties of the Cosmos; the first to pay attention to this number was an English astronomer, the late Arthur Eddington. But the physicist couldn’t come, and Hart appeared on his own, at about three, when the edition had already gone to press. Hart had become phenomenally adept at operating the computer. He had made a few simple improvements, which facilitated our tests enormously. We no longer had to pull the plugs out of the sockets, because there was now a button fitted to the cable, and we only had to press it to disconnect the teleprinter from the computer. As you know, it was impossible to ask it any direct questions, but you could send it any text you liked resembling the sort of impersonally edited information that is typical of press reports.

We had an ordinary electric typewriter that acted as a teleprinter. We would type out on it an appropriately formulated text and break it off at a preselected moment, so that the computer was forced, as it were, to continue the made-up “news.”

That night, Hart had brought the gambling dice, and was just arranging his things, when the telephone rang. It was the typesetter on shift, Blackwood. He was in on our secret.

“Listen,” he said, “I’ve got Amy Foster here, you know, Bob’s wife. He managed to escape from the hospital, stopped at home, took the car keys off her by force, got in the car and drove off, well, in the usual state. She’s already let the police know, and now she’s come over here to see if there’s any way we can help her. I know it doesn’t make sense, but that prophet of yours—perhaps it could come up with something, what do you think?”

“I don’t know,” I said, “I can’t imagine . . . but . . . you know . . . We can’t just tell her to go home. Listen, send her to us, have her come up in the service elevator.”

And as the ride was bound to take a while, I turned to Hart and explained to him that over the past two years our colleague, a journalist called Bob Foster, had taken to drink, and had even gotten wasted on shift, until finally he’d been fired, then he’d reinforced it with psychedelic drugs; in a single month he’d had two serious car crashes driving while semiconscious, and his driver’s license had been withdrawn. It was hell at home, then at last, with a heavy heart, his wife had sent him off for a detox cure, but now he had slipped out of the hospital, gone home, taken the car, and driven off who knows where—sure to be drunk, at the very least. Maybe high on drugs too. His wife had come here, she’d already told the police, she was seeking help, she’d be here in a moment. What did he think? Was there anything we could do? And I cast a glance at the computer.

As a man who’s not easily alarmed, Hart wasn’t surprised, and said: “What’s the risk? Please connect the machine to the computer.” I was just doing it when Amy appeared. From the sight of her we could tell she hadn’t handed over those keys at once. Hart offered her a chair, and said: “Well, ma’am, time is of the essence, isn’t it? So please don’t be surprised by any of the questions I’m going to ask you, but please just answer as best you can. First, I need your husband’s precise personal data: first name, family name, physical description, and so on.”

As she replied, Amy was quite calm, although her hands were shaking. “Robert Foster, 136th Avenue, journalist, thirty-seven years old, height: five feet, seven inches, brown hair, wears horn-rimmed glasses, on his neck below the left ear, he has a white scar from an accident, weight: one hundred and sixty-nine pounds, blood group O . . . Is that enough?”

Hart didn’t reply, but started typing. At the same time the following text appeared on the screen: “Robert Foster, resident at 136th Avenue, male, of average height, with a white scar below his left ear, left home today by automobile . . .”

“Please tell me the make and registration number of the car,” asked Hart.

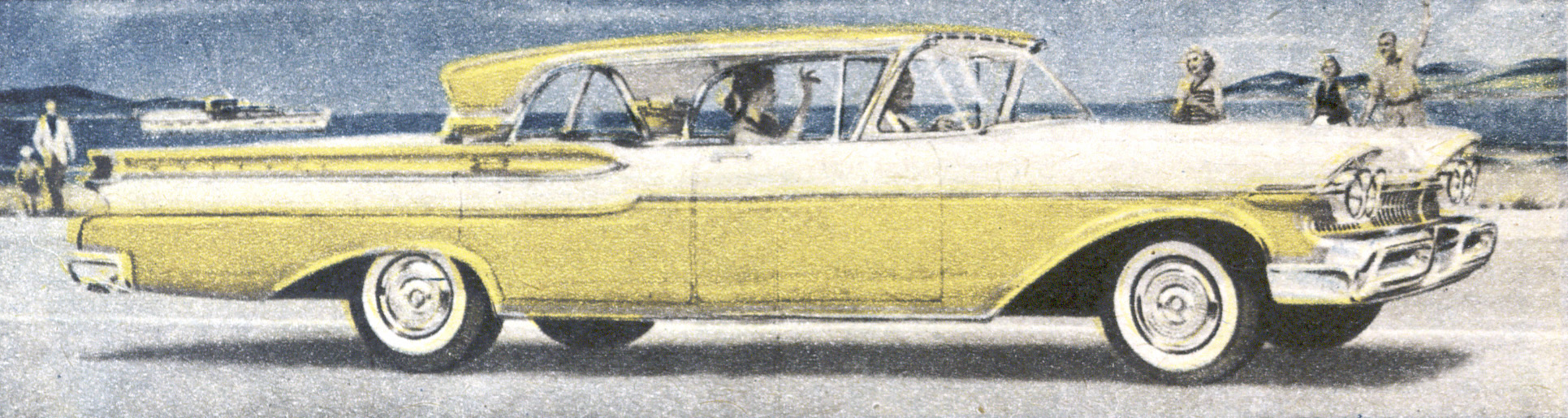

“It’s a Rambler, NY 657 992.”

“He left home today in a Rambler, NY 657 992, and his present location is . . .”

At this point Hart pressed the disconnector. The computer was left to its own devices. It didn’t hesitate for a moment, and the text on the screen continued: “And his present location is in the United States of North America. Poor visibility, caused by rain, with low-lying cloud cover, is obstructing driving . . .”

Hart reconnected the computer. He thought hard. He started writing again from the start, with the difference that after “location is . . .” he went on: “. . . on the section of road between”—and then he switched off the supply of information again. The computer continued without hesitation: “. . . New York and Washington. Driving in the outermost lane, he is overtaking a long line of trucks and four Shell tankers, having exceeded the maximum speed limit.”

“That’s something,” muttered Hart, “but the direction isn’t enough, we must squeeze out some more.” He told me to delete what we had and to start over again. “Robert Foster . . . etcetera . . . his present location is on the section of road between New York and Washington, between milestone number . . .” and here he disconnected the cable. Then the computer did something we had never seen before. It deleted part of the text that had already appeared on the screen, and we read: “Robert Foster . . . left home . . . and his present location is in milk on the shoulder of the road from New York to Washington. It is to be feared that the loss suffered by Muller-Ward Inc. will not be covered by the United TWC Insurance Company because the policy that expired a week ago has not been renewed.”

“Has it gone crazy?” I said. Hart signaled to me to sit quietly. Once again, he started writing, got to the critical point, and typed: “. . . his present location is on the shoulder of the road from New York to Washington, in milk, in a state . . .” Here he broke off. The computer carried on: “. . . that renders it unfit for consumption. A total of 766 gallons has escaped from both tankers. At current market prices . . .”

Hart told me to delete that, and said to himself: “A classic misunderstanding, because syntactically ‘in a state’ could have referred either to Foster or to the milk. Once again!”

I reconnected the computer. Hart doggedly wrote out the bizarre “report,” but after the milk, he put a period, and bashed out on a new line: “Robert Foster’s state at the present moment is . . . ,” then broke off; the computer froze for a second, then cleared the entire screen— before us we had an empty, hazily shining square without a single word, and I admit that I could feel my hair starting to stand on end. Then this text appeared: “Robert Foster is not in any particular state, because in a Rambler automobile NY 657 992 he has just crossed the border between states.” What the devil, I thought, sighing with relief. Hart, his face twisted in an unpleasant smirk, once again told me to delete everything, and typed it all out from the start. After the words “Robert Foster is at present in a place whose location is . . . ,” he pressed the disconnector. The computer went on: “. . . various, depending on the views held by each individual. This should be regarded as a matter of personal opinion, which, according to our customs and our constitution, no one can be forced to share. In any case, that is the view of our journal.” Hart stood up, switched off the computer, and nodded to me discreetly to send off Amy, who seemed not to have understood any of this magic. When I came back, he was on the phone, but he was talking so quietly that I couldn’t hear a word. Once he had hung up, he looked at me and said, “He drove down the oncoming lane and collided head-on with the tankers, which were taking milk to New York. He lived for another minute or so, once they’d pulled him out of the car; that’s why at first he was described as being ‘in milk.’ The third time I repeated that bit, it was all over, and indeed, there could be various opinions about where one is after death, or even whether one is anywhere at all.”

As you can tell, making use of the extraordinary opportunities that progress gives us is not always easy, not to mention the fact that it can be a rather horrifying game—considering the mixture of newspaper jargon and boundless naïveté or, if you prefer, indifference to human concerns that electronic machinery inevitably shows. In your free time, you can discuss what I have told you. I myself have nothing, absolutely nothing, to add. Personally, I would rather hear some other story now, and to forget about this one.

(1976)

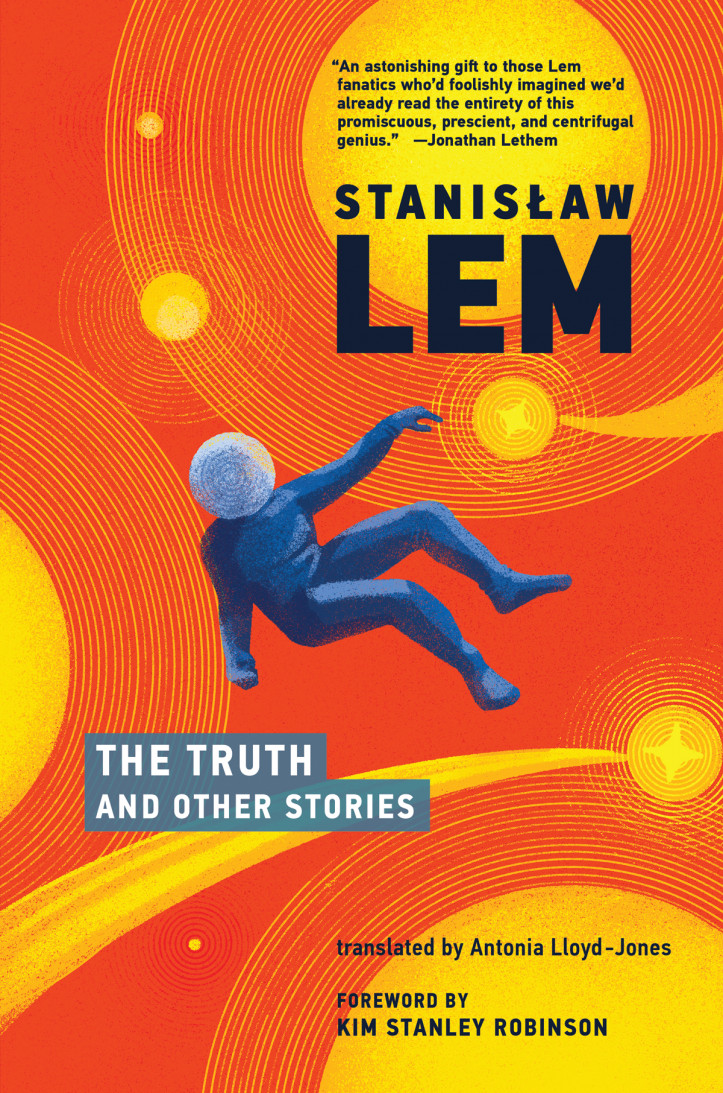

137 Seconds is an excerpt from The Truth, and Other Stories by Stanisław Lem, published by The MIT Press in September 2021 and translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.