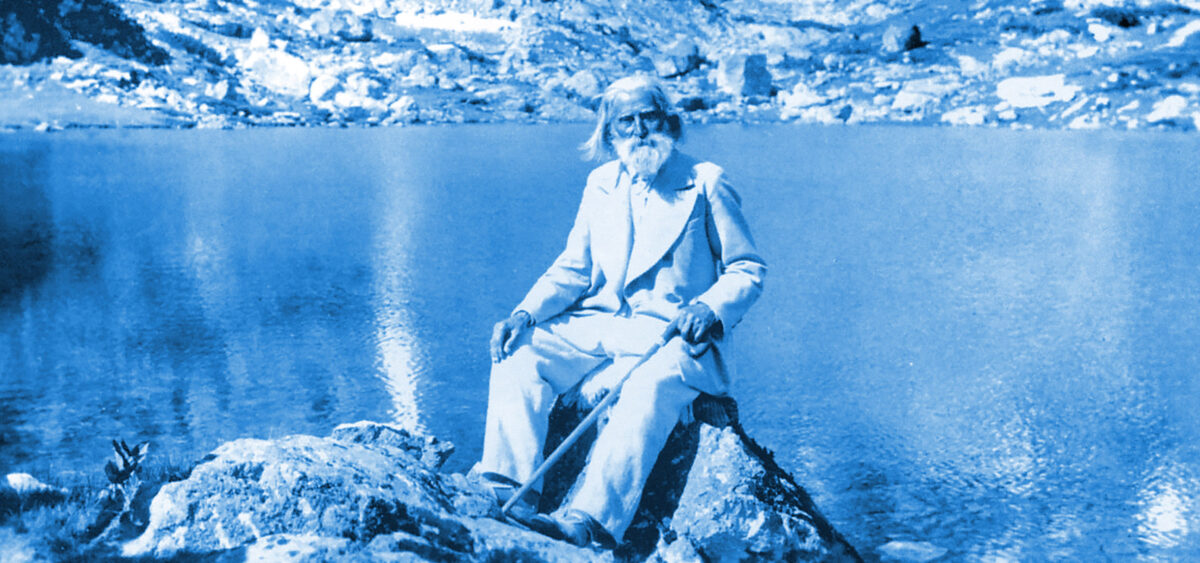

He believed everything to be connected and part of a greater unity. Perhaps there was something that made him so sure of that.

In the summer of 1973, philosopher Ervin László had become tired. The great thinker had just completed another global UN project, and, despite invitations from prestigious universities, he chose a ruined chapel overgrown with tall grass. His intuition—which had saved his life and led him to discoveries many times before—suggested it was a good place for a year of rest. That year has stretched into almost half a century now, and László’s Tuscan house has become the perfect place for deepening his subtle relationship with the universe.

The beginning was bright and happy. He was given the name Ervin because of how original it was. No one in the family of the boy’s father—a Hungarian shoe manufacturer—had one like it. The year was 1933, and business was thriving. Ervin grew up in a spacious apartment in Budapest, overlooking the park and the city’s spectacular architecture. He loved music. His mother was his first piano teacher. Ervin wasn’t good at reading sheet music—and it would stay that way—but, when he played, it was as if he breathed the music; like he was in a different world. Beethoven’s Appassionata by Wilhelm Backhaus was his favorite. He played it over and over again, as it transported him to a land of unknown wonders.

Viewing music as a vehicle into a different dimension is apt in the context of László’s biography—because just one trajectory of existence is not enough to describe his life and philosophy. He was so eager to perfect his own interpretation of Appassionata that his mother brought him to Professor Székely, a prominent figure at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music in Budapest. Upon hearing the boy play, the stately professor exclaimed, “Simply genius!” and the mother just nodded, unsurprised. They went back home, but from then on nothing was the same. The life of a brilliant pianist had begun.

A Genius in High Society

At the sight of the first poster announcing his concert with the Budapest Symphony Orchestra in 1942, nine-year-old Ervin fell over running to the bulletin pole. Because it was customary for