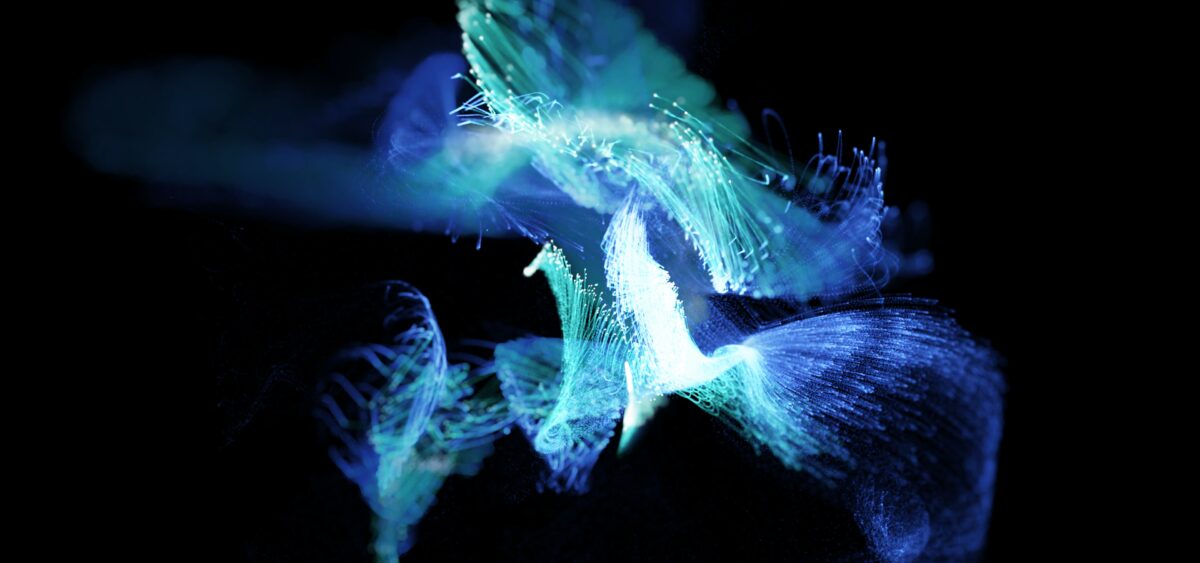

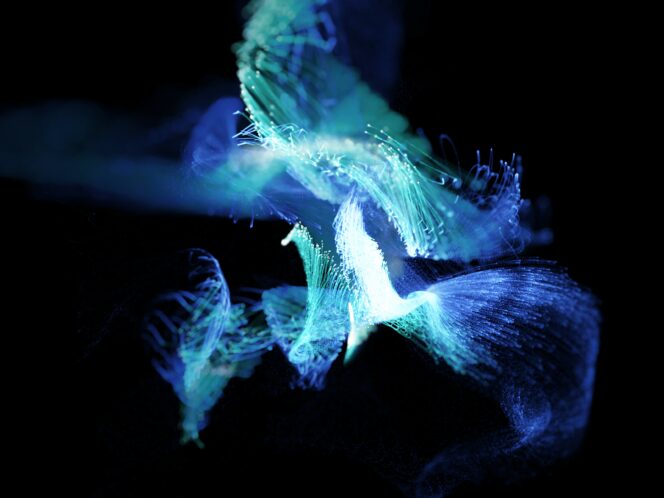

Holography is a dream come true, which artists have fantasized about for centuries. At the turn of the 1960s and 70s, when technological advancements enabled the creation of three-dimensional holographic images, there was the whiff of an artistic revolution, the greatest one since the invention of photography in the 19th century. Yet, the revolution never happened and it leaves one wondering why.

People carry holograms with them every day. At least, those who use credit cards do—a small holographic image is one of its basic security features. The technology is used for reading barcodes in stores, and there is even a holographic principle, according to which the universe is… one huge hologram. Only an expert in physics could explain the exact details, but the important thing is that supposedly the proposition helps overcome the contradictions between scientific notions about the nature of the universe on a micro and macro scale. In other words, it reconciles the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics, which is no mean feat. If the universe is an enormous hologram, it’s odd they’re so rarely encountered in galleries, and that instead of admiring these unique images in museums, they usually only appear on credit cards.

An Object in Amber

The classic