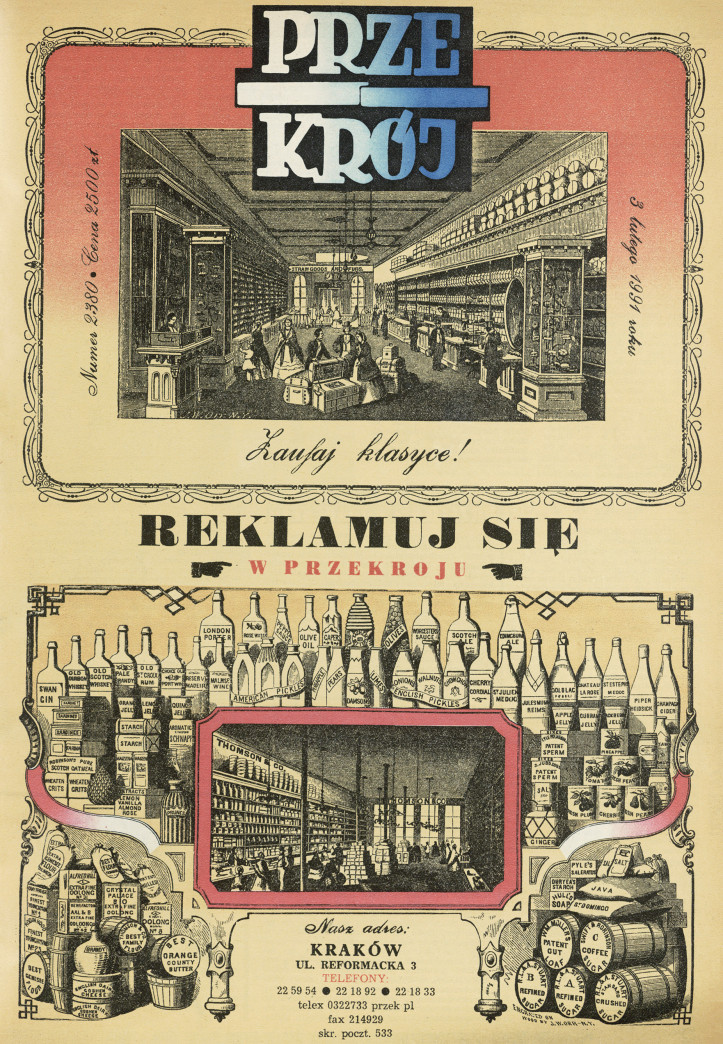

This featured cover from 1974 is a fine example of the Iron Curtain’s practical applications. From the mid-1940s, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, Marian Eile (often accompanied by his deputy, Janka Ipohorska), would travel to Paris to spend a modest hard-currency allowance on literary journals and fashion magazines. “Przekrój” would later ‘borrow’ illustrations, topics and even entire articles from them, with no regard for copyright. Parts of photographs and drawings would occasionally end up on the covers, and the magazine’s designers would ink in extra details, signing them ‘By The Editorial Staff’. Nowadays, it would have ended in court.

Not only is this work older than Guernica, it is also much larger. It was commissioned by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes as the curtain for the play Le Train Bleu, staged in Paris in 1924. The painting had not been on public display for almost 80 years, and in 2010 when London’s Victoria and Albert Museum finally decided to exhibit it, it took 15 workers to hang the canvas.

Picasso and “Przekrój” had much in common, apart from the fact that they both began with ‘P’. “Przekrój” was a fan of Picasso, thanks indirectly to the pre-war Wiadomości Literackie, where the young Eile worked and first encountered the artist’s paintings. Wiadomości’s editor-in-chief, Mieczysław Grydzewski, had been interested in his work since the 1920s. When Eile became the editor of “Przekrój”, he kept up that interest. Picasso was first published in the weekly in February 1946 and was then featured regularly. “Przekrój” even named 1959 its Year of Picasso, reprinting one of his works every week.

Although readers had already had a chance to acquaint themselves with Picasso previously, the first publications of his works triggered a public outcry. Angry letters poured into the magazine’s offices, but Eile ignored them completely. The magazine was supposed to be a window on the world, and the world adored Picasso – on both sides of the Iron Curtain – albeit for very different reasons. To quote one of the painter’s lovers, Françoise Gilot (or one of Picasso’s wives Jacqueline Roque): in Russia they hated his work but liked his politics, whereas in America it was the reverse.

Picasso joined the French Communist Party in 1944 and remained a member for life. He also made donations to the party and its related institutions, and designed propaganda posters and tracts, the most famous of which was the dove of peace symbol. His sketch caught the eye of party colleague Louis Aragon when he was visiting Picasso’s studio. Picasso later questioned why his drawing of the bird had been chosen as the emblem for the World Peace Council set up by the Communists: “As for the gentle dove, what a myth that is! They’re very cruel. I had some here and they pecked a poor little pigeon to death. […] They pecked its eyes out, then pulled it to pieces. […] How’s that for a symbol of Peace?”

There is still a debate today as to whether the artist truly was politically conscious and committed, or merely figured in the party ranks as a ‘useful idiot’ whose fractiousness was tolerated because of his generous donations to the party coffers, and his fame (in which the French Communist Party also basked).

One way or another, Picasso visited Poland in 1948. He only accepted the invitation after the Polish government guaranteed him a private plane and promised that the visit would last for no longer than three days. The artist was among 400 delegates from 46 countries who had been invited to Wrocław for the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace. The propagandistic aim of the congress was to convince public opinion worldwide that the Communist Bloc was advocating peace, while the West was threatening it. A conflict arose at the congress when a Soviet delegate, Aleksander Fadeyev, labelled creators of ‘decadent’ Western art and literature as hyenas and jackals. Some of the Western delegation left the hall in protest. Picasso did not react, but later claimed that, behind closed doors, he had given Fadeyev a real ear-bashing and even branded him a Nazi.

The promised three days eventually stretched into two weeks, during which Picasso was taken all around Poland to show off the new leadership’s achievements. A “Przekrój” correspondent, Leopold Tyrmand, even managed to discuss all the burning issues of the time with the artist. This he described as follows:

“Picasso was perpetually surrounded by a crowd of people, indefatigable, forever signing autographs, always smiling and polite. The small, dark eyes of this short man with his tanned complexion were constantly smiling. Finally, this breathless “Przekrój” reporter squeezed through the crowd of admirers and blurted out:

‘Monsieur Picasso, what do you think about peace, war, the Recovered Territories Exhibition, Polish food, the nationalization of industry, Wrocław under Poland, Polish energy, functional architecture, the Oder–Neisse line, the refugee problem, Polish hospitality, German revisionism, Wall Street machinations, your own influence on contemporary painting, imperialism, Cubism, Jerzy Andrzejewski, the reconstruction of Szczecin, and the last Olympics?’

Picasso looked over at “Przekrój” and smiled. Nodding his head, he replied:

‘Oui…’

And that said it all.”

The renowned Spaniard first met Marian Eile while visiting “Przekrój”’s offices during his forced tour. The two men liked one another, as they had a lot in common. Eile was also a painter; they shared an almost compulsive interest in women and both flirted with communism, although Eile was never a party member. The artists remained in touch for some time and then, in 1954 or 1955, Picasso showed up unannounced in Eile’s office. Apparently, it was the only time in the editor’s long and fascinating life that he had jumped out of his skin in surprise.

The visit was all because of the writer Sławomir Mrożek, ‘the girl with the ponytail’, and a sheepskin coat. Picasso’s last muse, Lydia Corbett (Sylvette David), had seen a photograph in a foreign newspaper of Mrożek wearing a sheepskin coat, and fell for it immediately. Enchanted by the girl, the artist came to Poland and headed straight for “Przekrój”’s headquarters. It was quickly established that the coat had been purchased in Nowy Targ, so the magazine’s secretary, Merka Ziemiańska, set off in a car to accompany the visitor on his quest. It ended successfully: the artist bought the sheepskin coat (or even two), which only served to strengthen the mutual admiration between Picasso and “Przekrój”.

The featured cover is a distant echo of that friendship.

Click here to see more covers from “Przekrój”’s archives.