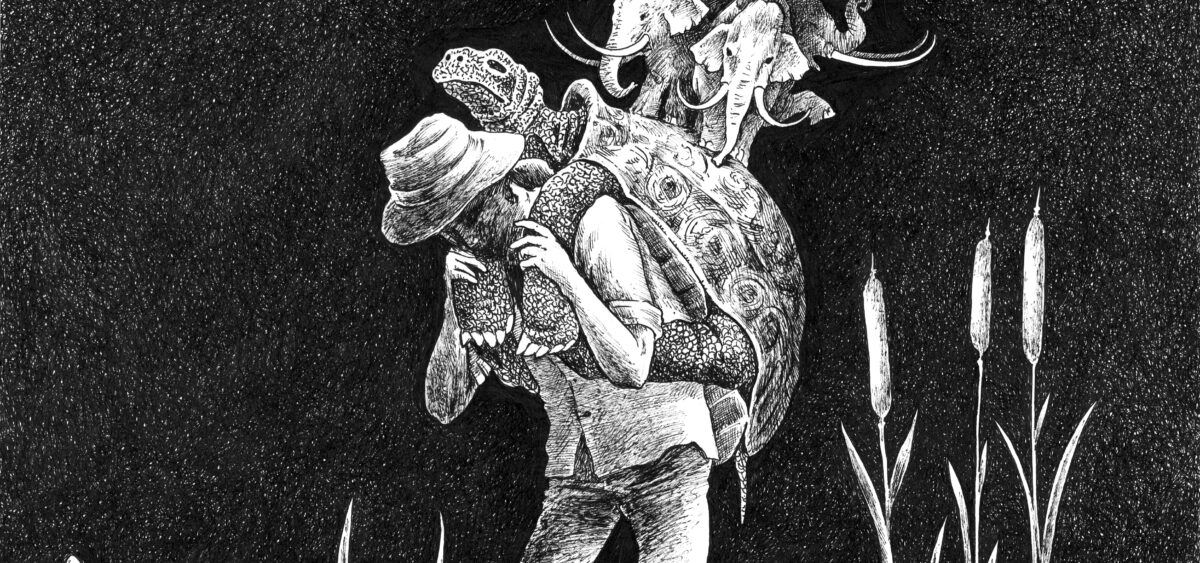

Europe, the near future. One morning, the sun doesn’t rise for some mysterious reason, and most sources of energy lose their properties.

Cities regress to the early medieval condition, and Herodotus’s Histories seems to shed more light on “dark Europe” than the local newspapers with their fake news. The hero of Night, The Bookman, decides to sell off his most valuable possession—a huge library of books—and use the income to make the long journey to Nepal, where his girlfriend was when the skies became dark. In the prologue, we meet The Bookman and his girlfriend, and observe the first signs of the impending “dark times”.

There is no expectation without anxiety. I had been waiting for this call for eleven months, and that was still when the phrase “to wait for eleven months” had a semblance of meaning. The phone rang only when I had finally lost all hope. This is how it all began.

What was I doing at that time? It won’t be easy to explain. After all, what is loneliness? It is a state when nothing is happening to you that you haven’t conceived yourself. Correction: I am not alone. I have Gerda. But the girl had already had her meal and her walk, and was sound asleep in my bed, where, as a matter of fact, she wasn’t allowed to sleep. I know. In Belarusian, “dog” is a masculine noun, but I cannot change my friend’s gender just like that. At least not without her