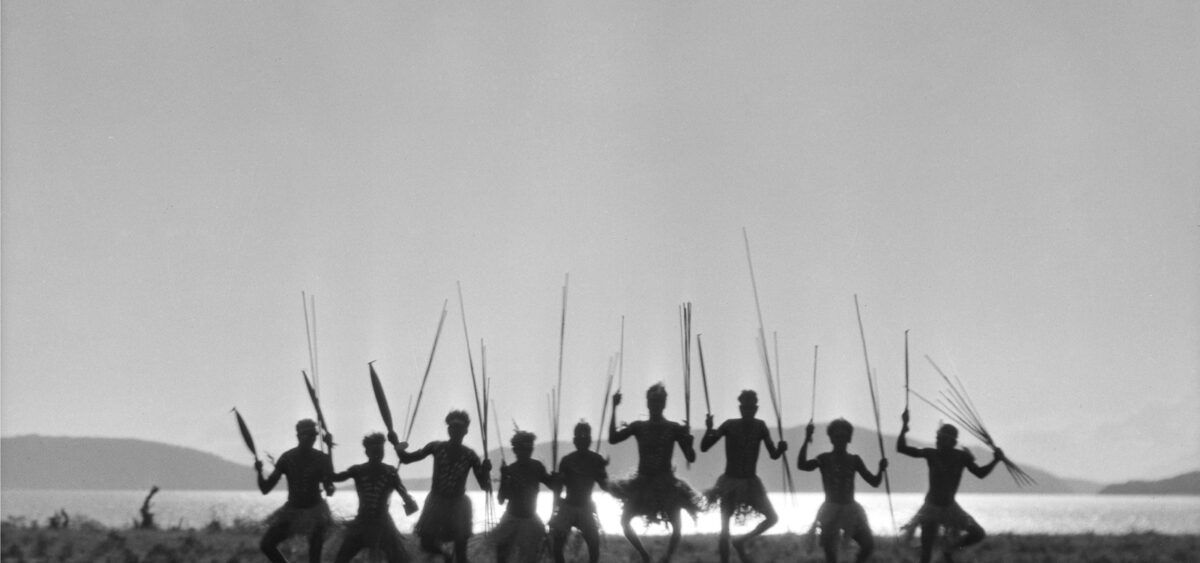

Palm Island is where, for many years, Australians were sending Aboriginal peoples. The shark-infested waters surrounding the island served as a natural barrier, stopping the prisoners from escaping it, explains traveller Bartosz Twaróg in conversation with Jan Pelczar.

I meet Bartosz Twaróg in a bookstore in Wrocław Market Square. He has just come back from a weekend spent in the nearby Owl Mountains. “It was a post-climate catastrophe landscape,” he tells me. We are going to talk about a place marked just as harshly by human activity as it was by natural disasters. The island’s location by the shores of Australia should be enough for us not to confuse its name with the artificial archipelago on the coast of the United Arab Emirates.

Jan Pelczar: Why is Palm Island such an extraordinary place on the map of Australia?

Bartosz Twaróg: Mainly because of its reverse proportions. Out of several thousand people inhabiting it, almost everyone is of Aboriginal descent. In multimillion cities such as Sydney, only several thousand Indigenous Australians live there. According to various estimates, 3000-5000 people live on Palm Island, and only about a hundred of them are white – mainly the infrastructure maintenance workers. The island is within the compass of the Great Barrier Reef. Its sister island, almost identical to this one, is a tourist paradise. But there are no tourists on Palm Island. When I was boarding the ferry, several people asked me if I was sure that’s where I wanted to go. All the other passengers were Aboriginals and white workers in work uniforms. The island’s isolation is, in most part, a consequence of its cruel past. Going there is like staring into an open wound that’s refusing to heal. 11 years ago, the island was listed in The Guinness Book of Records as the most dangerous area that is not a war zone. It got its place due