The year is 1976. In the village of Bronocice, in the district of Działoszyce in southern Poland, archaeologists from the Polish Academy of Sciences, aided by poacher Maniek Wróbel, have found the remains of a Neolithic vase near the Nidzica River. And what a find it is!

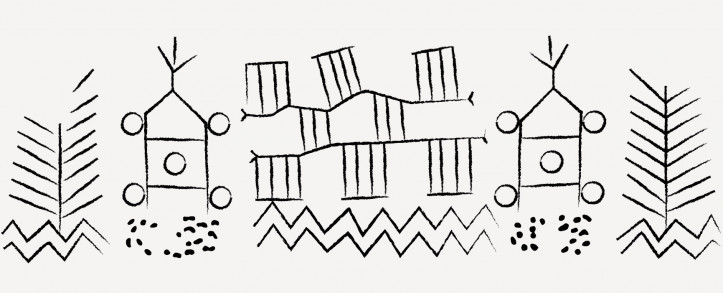

The vessel is decorated with an image of a cart driving through fields. Radiocarbon dating of the clay shows that the vase was made 5500 years ago, making this narrative design the oldest representation of a wheeled vehicle in the world. Simultaneously, it is proof of people’s knowledge of the traction wheel at that time. Older than the Great Pyramid of Giza, Socrates and Plato. Older than Jesus Christ and the Roman Empire. And older than the pictograms of carts from the Sumerian city of Uruk on the Euphrates.

The research is headed up by Professor Janusz Kruk from the Institute of Ethnology and Archaeology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, together with colleagues from the State University of New York. Every academic in Europe is talking about the village of Bronocice – especially the archaeologists – as are the people of Bronocice itself and the neighbouring villages. There is talk of the beginnings of civilization in Działoszyce, and the legend of Piast the Wheelwright is gaining a new dimension. The vase inspires literary works, as well as rumours about Lechites and aliens. Meanwhile, what has escaped the attention of four-wheel-fanatics (a rally is being planned along the vase trail) is an element of the ornamentation just as important as the first cart. A tree is growing at the side of the road along which the vehicle travels. The image of the cart is repeated five times around the body of the vase, and so is the tree. In a country whose trees have been very much on the chopping block of late, the oldest known representation of a roadside tree in the world has been found.

We will never know if it was cut down for road safety reasons or – as is often the case today – out of thoughtlessness or a desire for profit. What we do know is that it was clearly of great importance to someone from the Neolithic era. It must have been a significant element of the landscape in which he lived. Interestingly, although the body of the vase had enough space for birds, aurochs or deer, the Neolithic potter was inspired to make a solitary tree in the middle of a field part of the narrative design. Most experts agree that it depicts a cart driving through a patchwork of fields or village buildings. And then there’s the tree. The whole image is washed over by the waves of a river, presumably the Nidzica. We see its valley through the eyes of Neolithic man.

Professor Kruk

“The Polish People’s Republic was buying grain in the US” – thus begins Professor Janusz Kruk’s story of his discovery when we meet in his uncluttered office in Kraków’s Old Town. The vase is in the room next door, in a safe. “There were these so-called ‘grain debts’ that we had to pay back. The Americans wanted to research the beginnings of agriculture in Europe, so we paid off the debt in research studies, although they were paying for the excavations, as much as $30,000 per season! That amount enabled research in several sites over a few years. We were digging up the remains of the Neolithic highlands. North of the Carpathians, that means the period from 5000 to 1500 BC.”

“Americans, money and treasure?” I’m excited, maybe a little too excited.

“In the conservation sources there were mentions of finds from near Działoszyce on the Nidzica River, so we started there on Łysowiec hill. One day a certain Mr Wróbel came over, had a look around and said: ‘What are you looking here for, go to Baski, you’ll find beads.’ Baski is a hill a kilometre away, on the other side of the valley in Bronocice. We found a lot of ceramics and old tools there. And the ‘beads’ turned out to be spindle whorls. People believed that the angels wore them around their necks. And when they lost them, the beads fell onto the fields.”

“And how did you find the vase?”

“While we were researching a rubbish tip from the Funnel Beaker Culture period. One of our workers – and we had a hundred of them, mostly locals – called me, joking that they’d found an image of the Soviet Lunokhod [a series of robotic lunar rovers – trans. note]. Among other artifacts were these vase fragments with a strange ornamentation. In Bronocice we found about 70,000 fragments of ceramics from several thousand vessels, and there was only one pattern like this. It wasn’t a particularly graphic, artistic culture.”

“What did they drink from these cups?”

“Other than water and milk, it’s really hard to say what they drank. But they drank something, without a doubt.”

“Did you realize the importance of the discovery right away?”

“Only over time. Scientific discoveries usually fare better over time. We have the opportunity to verify what we want to publish. Today we know that this is the oldest representation of wheeled traction known to man. The Bronocice finding is older than the representations of vehicles from the Tigris-Euphrates Basin, and those from further east are two-wheeled.”

We talk for a long time about the people of the Funnel Beaker Culture. They were farmers and hunters. They raised cows, pigs, goats and sheep. Stalks of cereal have survived in the fire-burned clay that was used to plug wooden walls, the fire having baked the clay and preserved its contents. Charred vessels have been found to contain grains of wheat (emmer and einkorn), as well as barley, millet, and perhaps spelt.

“Though it may still have been a weed back then,” says Professor Kruk. “It is astonishing that the grains have retained their species characteristics for millennia thanks to fire, which we associate more with destruction than survival. Numerous bones and antlers suggest that the people hunted aurochs, deer, wild boars and birds. The mammoths were long gone, although the last of the species might have lived on Wrangel Island in today’s Yakutia. Iron and bronze were unknown, and copper was rare. And miraculously, the drawing on the vase has been preserved. It’s a rebus, a representation of that reality. A four-wheeled cart, that’s for sure. Geometrically correct, because in descriptive geometry the wheels are placed on the sides. There are other elements of the narrative: fields or buildings, water, most likely a river. And a solitary coniferous tree. There are dozens of interpretations. Probably it’s a cart carrying crops through a field. A letter from the past. It’s hard to decipher, but we definitely have a tree here. A straightforward, simple representation of a tree. Children still draw like that today, I drew like that myself.”

“Did you know that, as well as the cart, you’d found the oldest image of a roadside tree?”

“Well, there you go. But trees are in a bad way these days.”

The vase

The professor brings the vase over and hands it to me with confidence. As someone who’s always breaking glasses, I panic slightly. I note with surprise that the vase could have been used for cooking, and instinctively check to see if there’s any food left inside.

“No organic remains have survived,” says the professor.

The vase (or pot) has a volume of about 1.5 litres. Nearly half of the vessel survived, the rest has been filled in with plaster. The pattern was carved with a bone, maybe a splinter, and is remarkably deep. It’s so clear that it looks like it was done recently. I examine some prints (fingers?) and insertions, something that was adhered 5000 years ago and has lasted through antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, Romanticism and beyond.

It’s hard to know what kind of tree it is. The simple depiction – a two-sided ‘comb’ with teeth facing upwards – looks a lot like a fir branch. The classic herringbone pattern can be found in folk adornments in various regions of Poland and across Europe. Was it a solitary fir? The Funnel Beaker people to whom the potter belonged hunted, cleared forests and cultivated fields. At the dawning of today’s landscape in prehistoric times, did people appreciate the importance of trees in a view, unlike today’s road builders and village mayors? A mysterious someone certainly did. Thousands of vessels, and just one drawing like this. For thousands of years. I’ll go out on a limb here and say that this was drawn by someone who would defend trees today.

Among the professor’s many books containing studies of excavations, featuring hundreds of drawings from pots found in Bronocice, I come across one with an identical image of a tree! Made in the same way! Is it the work of the same tree-lover from 5000 years ago? The professor confirms that it came from the same site and period. For decades before the vase and many years after, this pattern was not recreated on any of the other 70,000 fragments discovered. Why?

“The Funnel Beaker people were mainly chopping trees down,” explains the professor. “They used flint axes. The part of Central Europe they inhabited, today’s Germany, Poland and Ukraine, used to be covered in forest. The loess hills by the Nidzica River were covered with coniferous woodland, and in some places broadleaved forest with linden and oak. They used up to 3.5 kilograms of wood per day per person just for heating, lighting and cooking. Not to mention the extra amounts they used to build houses. They were simple constructions assembled in a skeleton, log upon log. We’ll probably never know what they called them.”

Because we don’t know who they were, where they came from, or even what language they spoke. Their language might have been Indo-European, or maybe Altaic.

“They weren’t Slavs,” emphasizes Professor Kruk. “They didn’t have a written script, at least not that we know of. Nor do we know much about their beliefs, although they probably believed in life after death because their huge earth tombs contain items that would be needed in the afterlife. You could call them megalithic, although they were built of wood and earth, without rocks.”

I decide to visit Bronocice.

Bronocice

“To the forefathers and archaeologists” reads the inscription on the monument erected by the local government at the site of the excavations, on the elevated edge of the Nidzica valley. If I were from Bronocice, I would be searching for my roots in the Funnel Beaker Culture too, even though they weren’t Slavs. The inconspicuousness and modesty of the neighbourhood were highlighted by communist-era party notables, concerned that the Americans were coming to do research in such unrepresentative surroundings. “Couldn’t these excavations be done in the vicinity of a wealthier village?” they asked Professor Kruk.

The view from the hills stretches out wide, like on the body of the vase. A patchwork of fields, the road and river below. The current is barely visible, but 5500 years ago the Nidzica probably occupied the entire valley floor and could be seen at the foot of the opposite hills. A few isolated poplars complete the view. And a magnificent solitary tree in the distance, perhaps an oak. From the windows of the Kraków-Skalbmierz bus I hadn’t seen any ancient trees – which, after all, are a measure of the reflectiveness of the landscape – so these few poplars were a pleasant sight and allowed me to collect my thoughts.

There were no more ‘beads’ in the fields. I did find a carefully smoothed bone among the plough furrows, which Professor Kruk later confirmed to be a chisel. I also found a solid flint chip the size and shape of a fist, a remnant from chipping away at a flint block to make knife blades. According to Professor Kruk, flint was brought here all the way from Ukraine. So there must have been a road network that not only imported flint but also brine from Wieliczka. The item that brought me most joy was a fragment of deer antler neatly sharpened into what looked like the tip of a weapon. Could it have been used as an arrowhead?

Five hours passed quickly, much like 5000 years. Heavy rain was falling on Baski hill and we had to run for cover. Our return route snaked through the Nidzica valley, an asphalt road from Skalbmierz to Działoszyce. Bags of rubbish were floating in the river like colourful buoys. Tyres, cables and nappies were accumulated in picturesque patterns along its banks. The roadside shrubbery extended menacing, cracked offshoots, and the lower limbs and branches of the trees looked the same way, as if they had been pounded with the butt of an axe or a blunt instrument. I’d never seen anything like it – it looked like an act of vandalism. I was about to call the police when I learned that this was merely a way of maintaining the roadside greenery.

“That’s the result of a chain trimmer,” explained a middle-aged cyclist, sadly.

You really wouldn’t want to be part of such a landscape, to constitute an element of its entirety. I took photos of a few more tyres that had been abandoned along the Nidzica and imagined how a view like this would look on the sides of a clay vase. In 5000 years’ time, perhaps those tyres could be mistaken for the artistic conception of the potter.

Translated from the Polish by Kate Webster