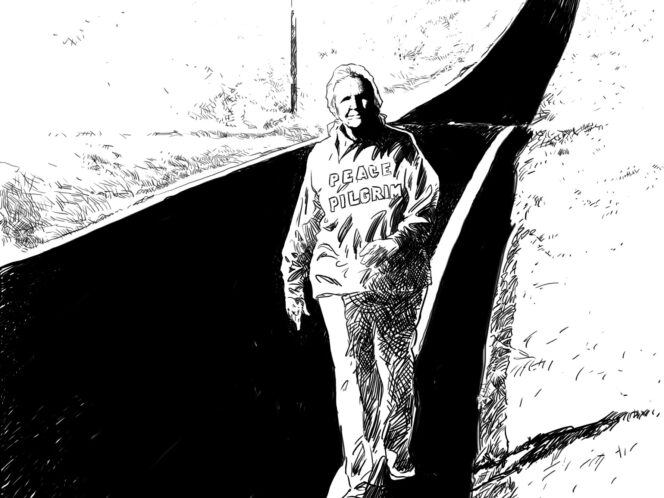

Mildred Norman believed that people are good, they just sometimes need a little inspiration to act. She chose her path to give it to them—literally.

New Year’s morning, 1953. The annual Rose Parade had begun in Pasadena. The streets were full of floats decorated with flowers, fairy-tale coaches, luxurious Porsche cars—all of them bearing the not-at-all discreet names of local businesses. American flags the size of bedsheets fluttered in the wind, scantily-clad cheerleaders danced, the jubilant crowd cheered. An archival film shows a gigantic pumpkin with holes for eyes, nose and mouth, through which amused people are waving. The pumpkin marches on, filling the whole frame. It’s like a carnival: an excess of shapes and colours, exaggeration everywhere, spectacular superfluity.

Mildred Norman stood out in the colourful crowd as she watched the parade. Grey hair in a loose ponytail, no make-up or jewellery. Modest, almost severe clothes: blue trousers, trainers, a roomy shirt and a simple tunic with the words “Peace Pilgrim” on the front, and “Walking coast to coast for peace” on the