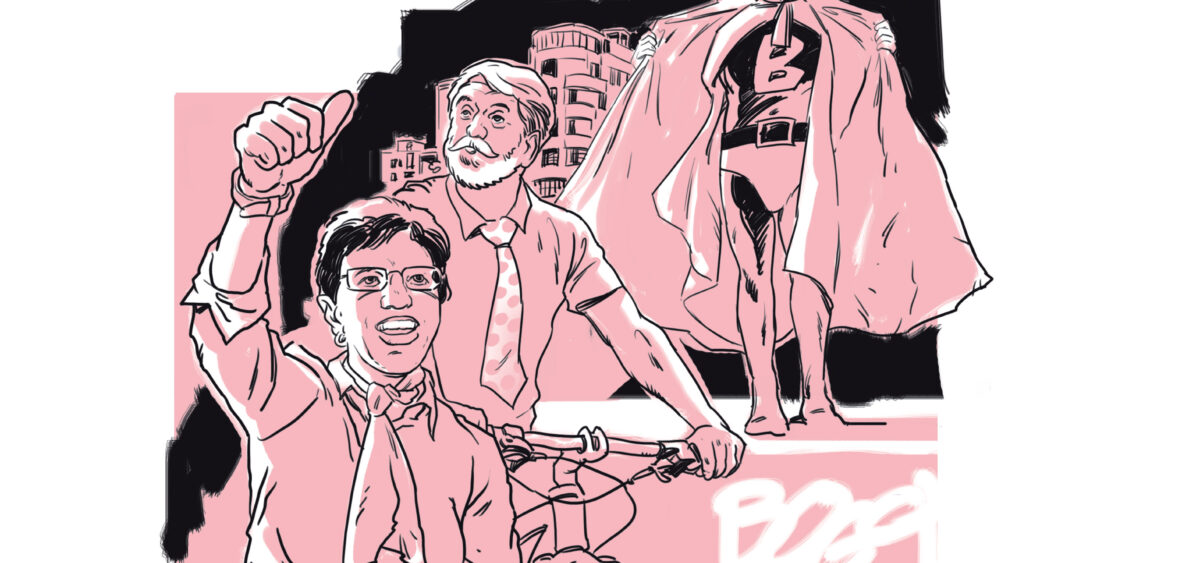

Can a superman, imaginative cyclist and fearless journalist make a revolution? Yes, but it will be a peaceful revolution. Its victim will be violence; its beneficiary – the capital of Colombia, fortunate to have great mayors.

On Sundays around noon, Bogotá doesn’t look like other big South American cities. In the streets of Colombia’s capital, with its eight-million population, commerce is flourishing. Some people are dancing; some are barbecuing. Older inhabitants are playing chess. The younger ones are betting at guinea pig racings. Yoga lovers are practising on the asphalt roads, right next to aerobics enthusiasts. You can spot some theatre troupes, clowns and jugglers, but mainly the cyclists. There are also skateboarders, scooter riders, runners, and people on wheelchairs, but no cars! This event is called ciclovía: a true celebration of cycling. Each Sunday, between 7am and 2pm, the mayor of Bogotá closes most of the main roads, i.e. nearly 300 kilometres. Sometimes, there are altogether 1.7 million eco-friendly single-track vehicles on the roads at the same time. This is a world record – nowhere else is the Critical Mass bike ride so popular.

It is hard to believe that 25 years ago, Bogotá – located in the Andes, at 2650m above sea level – was considered a fallen city. Tourists were afraid to go there (and to Colombia in general) and homicide rates were shockingly high. Socio-political life was dominated by corruption and violence. Many districts, especially the poorest ones, were controlled by gangs, and the inept, corrupt and intimidated police were too frightened to intervene. Those problems were exacerbated by the more than 50-year-long bloody civil war with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Kidnappings for ransom and large-scale drug trafficking were part of everyday life. In the selva – the Amazon rainforest – guerrillas kept people locked up in concentration camps for many years. Although Bogotá was rarely at the centre of events, it also witnessed some tragedies. In 2003, guerrillas perpetrated the bombing in the capital’s elite El Nogal Club, popular with businessmen. Dozens were killed.

Compared with other South American countries, Colombia was the place that people tended to avoid. Airlines cancelled their flights. Large companies withdrew investments. The country fell into chaos. Presidential candidates and activists committed to fighting corruption and lawlessness were assassinated one by one. Apart from the helplessness of the government, the country was also struggling with major economic problems and enormous social inequalities. Only a tiny fraction of those in power, including cocaine barons and guerrilla commanders, were getting rich. Most people were doomed.

In the last 25 years, however, Bogotá has b