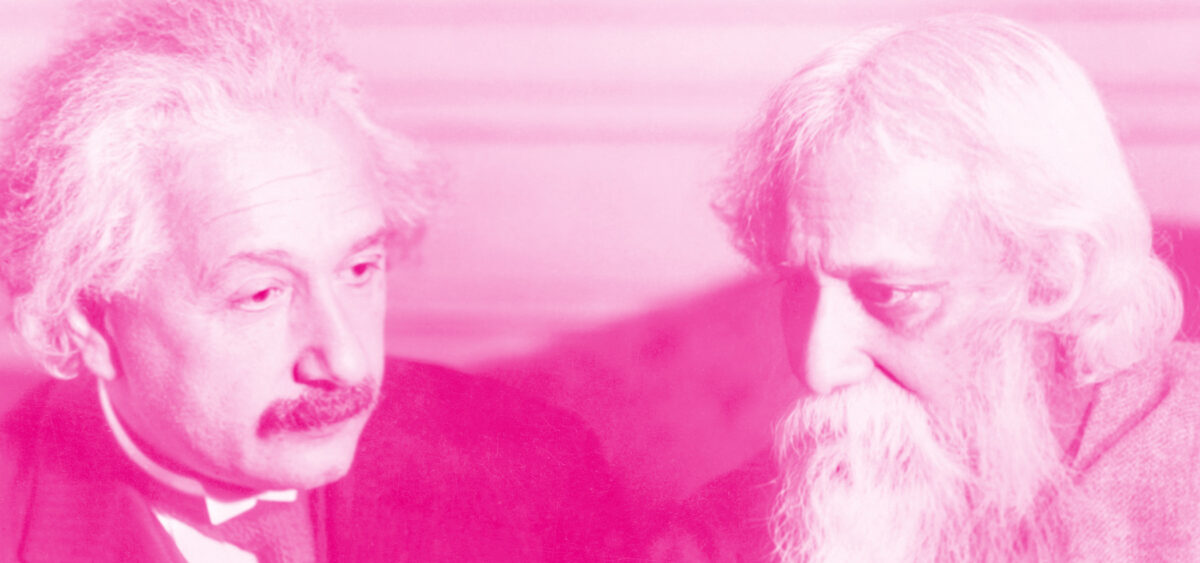

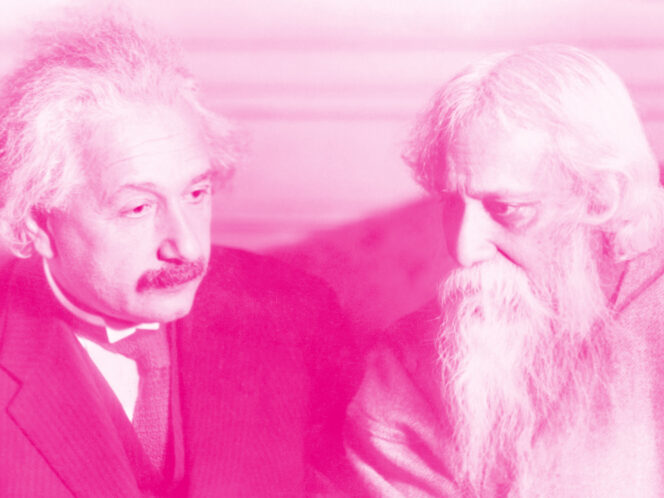

Rabindranath Tagore had two lives. For Europe, he was a mystical wise man, and for India, a troublesome prophet. This brilliant poet and thinker believed in human unity and a universal mind. He befriended Gandhi and Einstein, and founded a pioneering university to teach the wisdom of the East and West. What has survived of his belief in a united world?

He was one of the intellectual giants of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a genius in many disciplines—from poetry and prose to painting and music. He was also a pilgrim, presenting his universal spirituality from Japan to the US. After receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 (the first non-European to win the award), crowds greeted him everywhere and the elite took him for a guru, a spokesman for the cultural heritage of India, and a political commentator. Yet he chiefly considered himself a poet. Most of the time, in fact, he felt isolated. He had trouble making friends or even feeling intellectual kinships—throughout his life he had only a few such relationships. In his homeland he was embroiled in ethno-religious turmoil, overseas he struggled with being perceived through stereotypes of Asians. His ideals of freedom, the unhampered flow of inspiration, and spiritual development that transcended divisions, situated him outside of the epoch’s prevailing movements, watershed events, and social moods. In times when nationalism, racism, and militarism were on the rise—and which saw two enormous wars—his thoughts and works matured to become an antidote to these phenomena. The more the world succumbed to seeking differences and creating divisions, the more Tagore focused on what was deeply and incontrovertibly human. This is why now, when history has come full circle, his thoughts may bring solace; after decades of seeking commonalities and peace, the words “war” and “border” are again making their comeback.

In a Temple of Literature

Tagore lived to be eighty, and compared his time on Earth to the life of a tree—he was independent, yet joined with nature. He thought development was the foremost task. A simultaneous belonging to the natural and humanist worlds seems at the heart of his convictions. He was indebted to his predecessors for much of his outsider stance, preaching the unity of all existence. He was born into a privileged and rebellious family. One of his great-grandparents, a Hindu, married a Muslim, and from then on, Tagore’s family was sidelined in the Bengali social structure as odd and tainted.

The spacious family residence, Jorasanko Thakur Bari (the House of the Thakurs, whose noble name the British pronounced “Tagore,” and so it stayed), still stands in the north of Kolkata. One need only enter the gate to feel the peace and calm, away from the bustle. Yet apart from silence, the house offers little: a few pieces of furniture have survived, but the decorations, dishes, and books have gone. Young volunteers guide you through the drafty rooms, mainly talking about