Chinese medicine focuses on the treatment of the whole organism. It treats the human body as a microcosm. If one element breaks, everything goes wrong. This holistic approach, known for thousands of years, now inspires Western medicine. It is becoming increasingly clear that treatment is influenced by the psyche, weather and diet.

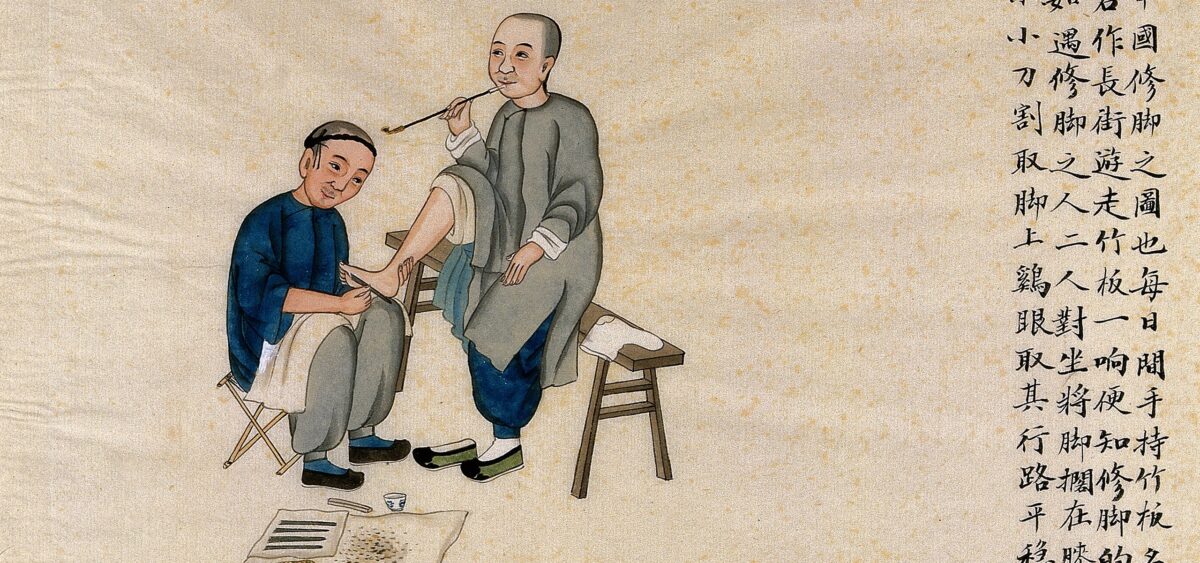

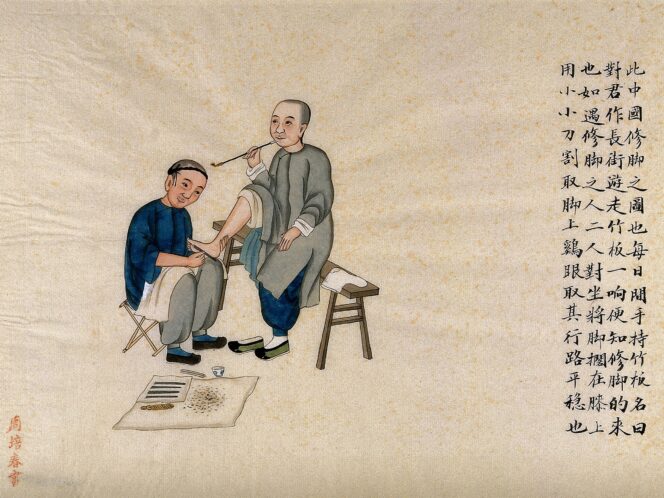

Chinese medicine is sometimes treated in the West as a curiosity rather than a fully-developed medical therapy; it is usually associated with acupuncture and massage (acupressure). Without a doubt, these elements do occupy an important place in the Chinese art of healing, but this is only the tip of the iceberg. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), reportedly up to 5000 years old, comprises extensive knowledge combining various fields, and the proposed therapies are considered effective.

In one of his books, Edward Kajdański, a Polish writer and diplomat born in Harbin (former Manchuria), cites a story from the life of Sun Simiao (541/581–682 CE), considered the most outstanding doctor in the history of China. The book praises the mastery that Chinese doctors have achieved in diagnosing a patient from the pulse. Sun lived in the mountains and led the life of a hermit. On one occasion, Emperor Taizong summoned him to his court to examine the empress, but he was not allowed to touch or even see her. The only tool he could use was a silk thread, with which he could sense the pulse of the woman sitting behind a screen. The contrary empress first attached the thread to the leg of the table, then to the paw of her dog. The doctor saw through both tricks, so the empress finally gave in and tied the end of the thread to her wrist. Based on her heart rate, Sun sensed that the woman was pregnant.

Sounds unbelievable? Perhaps, but Marek Kalmus – founder and director of the Institute of Chinese Medicine and Health Prophylaxis, honorary chairperson of the Polish Society of Traditional Chinese Medicine – believes that Chinese medicine can indeed work wonders where Western doctors are helpless. “I first encountered Chinese medicine in Tibet, in the winter of 1986. I had lost more than 10 litres of fluids in a few hours, and the lack of infrastructure ruled out the possibility of calling an ambulance. My travel companions knew Chinese medicine and with their bare hands pulled me out of the agonal state, without medicines or a drip, which from the point of view of Western medicine is incomprehensible. A day later, I walked